George W. Bush's reelection, and the fear that the newfound Republican vote hunting mettle behind it might presage a generation out of power for Democrats, brought new urgency to the left’s previously fitful efforts toward innovation. In late 2004, Laura Quinn called former Democratic National Committee colleague Debra DeShong and asked her to come to the consulting firm Quinn owned. Quinn’s desk was covered with newspaper and magazine clips about how Bush had won, many of them lionizing Karl Rove.

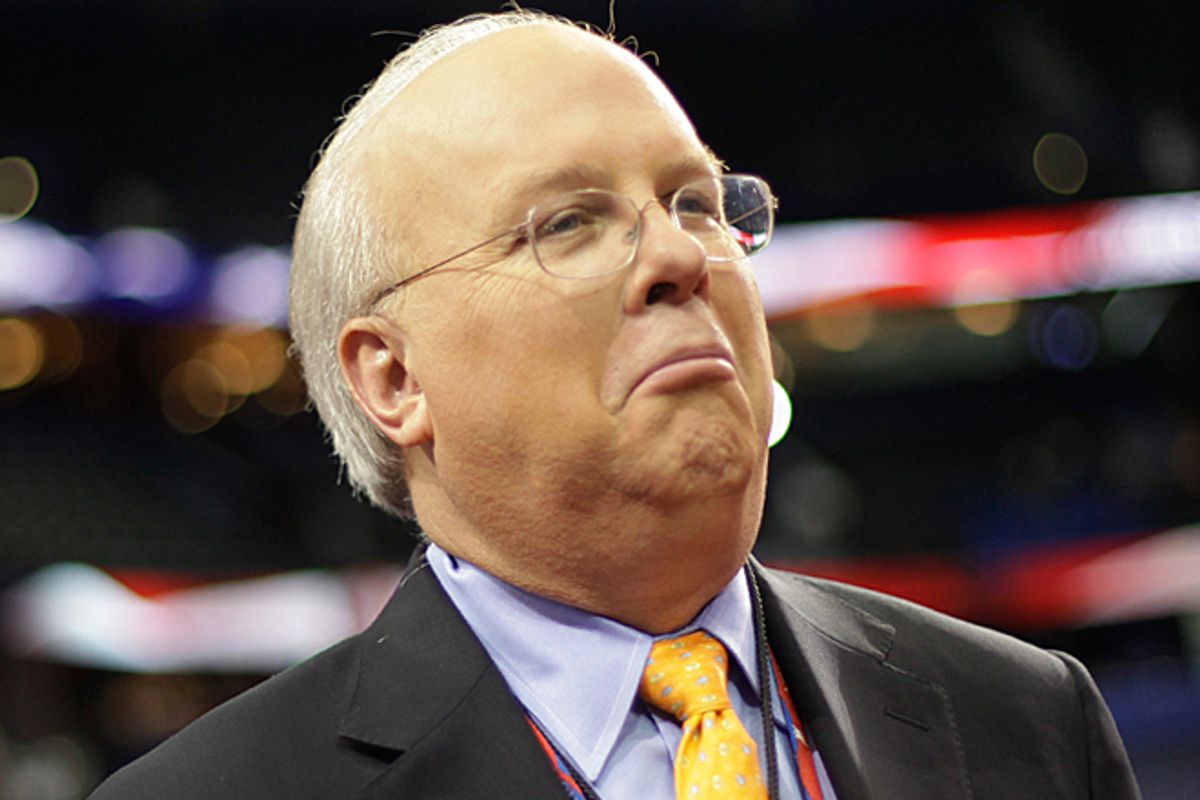

It is common for operatives to spend much of their time trying to figure out what the opposition is up to, but Quinn’s fixation on Rove had risen to the level of obsession. She kept easily accessible on her computer desktop the video of a 1972 CBS News report in which Dan Rather visits the Committee for the Re-Election of the President to marvel at the latest techniques being used to support Richard Nixon’s reelection, including the earliest efforts at data-driven direct-mail fundraising. The correspondent then travels to the basement, where he meets the executive director of the College Republicans, busy plotting Nixon’s youth registration efforts. “Young people have got to reach other young people, and that’s what we’re seeking to do,” says a 21-year-old Karl Rove, decorated with glasses, a tie and vest combination, and luxurious sideburns.

Now, while others who had played a role in Kerry’s campaign were scattered on tropical beaches trying to put 2004 behind them, Quinn found a sense of purpose in her Rove clips. She marveled at the way he had outfoxed the left at the aspects of campaigning where it had claimed mastery, and she was intent on reverse-engineering his methods from the general descriptions that had appeared in newspapers. “She was very upset about losing the election,” DeShong recalls. “But she was so excited that she had figured out what Rove had done.”

In winter 2002, A set of PowerPoint slides had found its way into Democratic hands. The material alerted Democrats that the Republicans had turned their attention to turnout and had developed an intellectual infrastructure for their field operations that towered over anything the institutions of the left had ever built. But hardly any details about Alexander Gage’s microtargeting project had made it into the press during the election. Instead, the stories that had come out about the implementation of 72-Hour tactics had been ones Republicans wanted told. Quinn and her allies suspected that Republicans had sharpened their approach to voter contact, but never knew how.

After the election, Rove and other advisers revealed what they had been up to, taking what Democrats described as a “victory lap” for the so-called microtargeting methods that made them possible. Even though no Democrats had used the word microtargeting, several party operatives had arrived separately at the same basic insight as Gage. They knew large-scale surveys could isolate the influence of personal characteristics that were combining in ways imperceptible to traditional polls, and how to track back to find specific individuals who fit those categories.

A small group of veterans of the Kerry operation known as the BullsEye felt the greatest frustration as they read the press accounts of Gage’s triumph. The BullsEye, which commandeered a small room at headquarters hidden off to the side of the communications war room, was designed to be the tactical hub of Kerry’s general election campaign, where a constant pulse of data from battleground states would help redirect the candidate’s plane or a communications blast to the areas that needed it most.

One of the most important tools at their disposal was a master database that pollster Mark Mellman had built to contain all the interviews conducted by Kerry’s retinue of far-flung survey takers throughout the year. Before the Iowa caucuses, Ken Strasma, a former analyst for the National Committee for an Effective Congress, had conducted a 10,000-person poll to build a statistical model that could identify likely Kerry supporters for the candidate’s voter contact operation to target and turn out for the caucuses. But there was little interest from the campaign’s leadership; Strasma didn’t even speak with the campaign manager, Mary Beth Cahill, until well after Kerry’s dramatic Iowa victory. “It was just one of the things that wasn’t on her radar screen,” says Strasma. And when it came to talking to voters directly, Kerry’s targeters had trouble getting state directors to put aside their precinct-based strategies and use the new individual-level profiles instead.

That resistance finally began to crack after the election, as victorious Republicans flaunted their fine-grained knowledge of the electorate. In one particularly potent example, Gage told how his party had turned even shopping patterns into political intelligence, discovering that bourbon drinkers leaned Republican while cognac sniffers were more likely Democrats. “It just scared the shit out of all the Democrats,” says Malchow. “The best way to get anyone to do anything on the Democratic side — and I’m sure it’s the reverse on the Republican side — is to tell people that the Republicans are doing it. It doesn’t matter: the Republicans could be doing something completely stupid, but if you tell the Democrats they get scared and think they should do it. They all think the Republicans are smarter than they are.”

As Democrats learned more about the scale of what the Bush campaign had done, they realized that the opposition’s edge wasn’t about a particularly potent set of consumer files it had acquired but rather the political structure they had built around them. No Democrat, and certainly not Kerry, had invested as much in individual-level targeting as Bush had, or did so early enough to integrate it fully into the campaign’s operations. A Washington Post analysis of the $2.2 billion spent on the presidential campaign — split almost evenly between efforts on behalf of Bush and Kerry — concluded that Bush’s $3.25 million contract with Gage’s firm TargetPoint was among the best money spent that year. The Post story pointed to the increase in Bush’s turnout in Ohio, and included one quote from an anonymous Democratic operative declaring that the party’s targeting power was a full election cycle behind the Republicans’.

As Quinn explained these machinations to DeShong, she took out a paper napkin and started diagramming. She drew a line to represent the partisan continuum, from left to right, and then laid upon it a series of bars reflecting targeted messages. One bar symbolized “terrorism and late-term abortion for older Hispanics,” Quinn said, while another of different length was “terrorism and guns for male union members.” DeShong sat dumbfounded by the squiggly lines, until Quinn explained her point: Democrats were polling to make messages for broad audiences, while Republicans were modeling to match messages to specific audiences. They were able to do that because they had not only better data than the Democrats to find the voters they wanted, she went on, but also the statistical tools to profile those they couldn’t reach and nonetheless predict what views they were likely to have.

“Now we have to do it,” Quinn said. “And we have to do it better.”

- - - - - - - - - -

Laura Quinn was something of an accidental technologist: a communications aide always looking for the newest way to get a message out. After Al Gore's loss, newly elected DNC chairman Terry McAuliffe hired Quinn to prepare a report on the party’s tech infrastructure. “It was really a terrible mess,” Quinn says.

The physical decay of the Democratic National Committee was the inevitable result of a cycle of strategic disinvestment. The DNC’s election-year job was largely to be a fund-raising vehicle for the big-dollar contributions known as “soft money”: unrestricted gifts, often from union and corporate sources, that the parties could legally raise but candidates could not.

McAuliffe had risen in national politics as a fundraiser for Bill Clinton, and together they had helped to expand the Democrats’ reach into Hollywood and Wall Street wallets, narrowing the soft-money gap between the parties. But the DNC still lagged significantly in raising so-called hard money, small contributions from everyday people.

Quinn looked enviously at the RNC headquarters, two blocks away and across a set of railroad tracks. It had always been a more stable, centralized entity than the centrifugal DNC. National Republicans effectively ran their state parties from Washington, even paying the salaries of executive directors. Democratic state chairs, on the other hand, were frequently appointed by the governor or an influential legislator and felt little fealty to national leaders. As she closely examined parties’ spending over the previous two decades, Quinn marveled at how the opposition had repeatedly made farsighted investments in new communication technologies. For a generation, conservatives distrustful of the mainstream media had made a priority of finding new channels to directly address their base.

But when he became chairman in early 2001, McAuliffe was already looking ahead to the ways in which life would change under the campaign finance reform bill known as McCain-Feingold, which vowed to ban soft money. McAuliffe foresaw that the national parties would be forced to reinvent themselves as engines of small-dollar contributions. Ironically, the soft-money parity that McAuliffe had helped to achieve during Clinton’s presidency now made the party disproportionately dependent on a mode of giving that would soon become illegal. The DNC had to learn to talk to people.

In April, Quinn returned to McAuliffe with her assessment of the infrastructure, which was filled with reasons for alarm. McAuliffe fixated on one set of statistics: the DNC’s list of names — donors and volunteers, mostly — totaled two million, and for many of those Quinn feared the information on file was no longer current. The e-mail list included only 70,000 people. The party had little capacity to hunt for other loyal Democrats who could be converted into contributors.

The RNC had begun its own project to find Republicans in the late 1970s, hiring private vendors to collect information on voters in all 50 states, standardize its format, and develop a system that could be continuously updated with new voters, changed addresses, and expanded vote histories. The Constitution leaves responsibility for administering elections to the states, and RNC officials quickly learned what a roughhewn patchwork of laws and protocols had emerged to simply manage voter registration practices. In New Hampshire, each of the state’s 234 townships was responsible for maintaining its own registration records, many times on handwritten rolls stored in officials’ homes. In Montana, Republicans had to send someone to gather computer tapes from every court house in the state.

Quinn knew this history. But along with the technological and logistical hurdles, there was a political one: a network of state parties ready to thwart any of Washington’s efforts to seize one of their most prized commodities. In some cases, party officers used the list as a fund-raising device — presidential candidates in Iowa had to pay $40,000 for its list of past caucus participants. In other states, kingmaker state chairs considered the list a plum to be shared with party- endorsed candidates.

But McAuliffe was ready for the fight. The only path McAuliffe saw to hard-money parity ran through cycles of prospecting new donors, in the mail and online. To accomplish that on the scale he believed crucial, Democrats needed the list of 100 million new names, sortable by party registration or voting behavior, that would fill a national voter file. McAuliffe proposed a deal to the state chairs, that the DNC would effectively borrow their files, help clean them up, add new data like donor information and commercially available phone numbers, and then return them for the state party’s use.

The so-called datamart that McAuliffe helped to assemble was riddled with errors, and many state-level campaigns did not even know how to get their software to properly handle the information that was returned to them. But a roster of more than 150 million new targets was a great gift for the DNC’s fund-raising operation, just as liberals were getting energized. Merely by having built a website that could process new contributions online, they had begun to compete.

Copyright © 2012 by Sasha Issenberg. From the book "THE VICTORY LAB: The Secret Science of Winning Campaigns" by Sasha Issenberg, published by Crown, a division of Random House, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

Shares