JAMES BENNET WANTS US to have a conversation. The editor-in-chief of The Atlantic, who took the helm in 2006, has overseen a remarkable rise in the magazine’s fortunes and profile. He has turned The Atlantic from a money bleeder into a moneymaker, from a worthy but familiar cultural artifact into a brand chattered about by people who are not usually considered part of the chattering class. And what gets the most chatter of all are The Atlantic’s frequent, and frequently controversial, articles about gender issues.

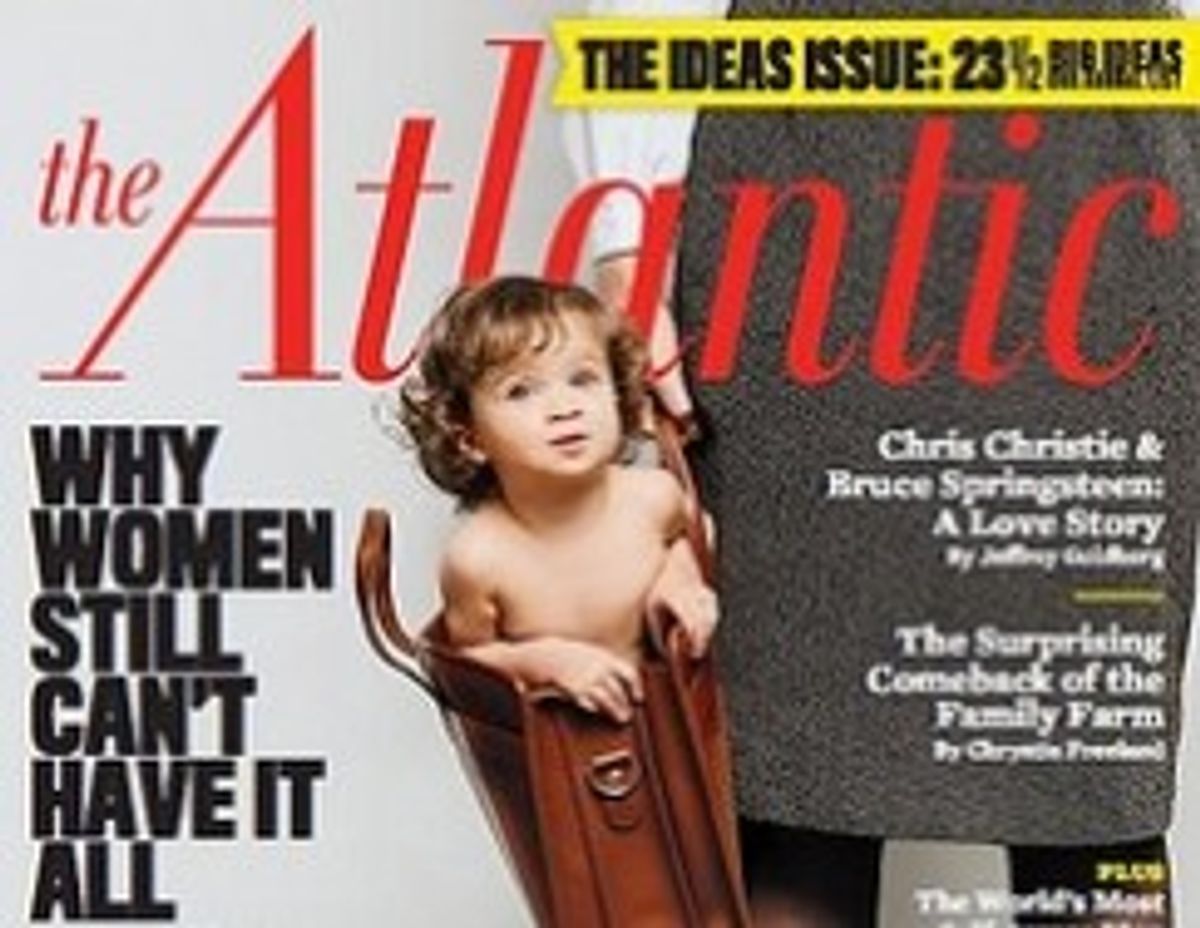

This summer, despite (or because of) the clichéd cover image of a toddler stuffed into a woman’s briefcase, Anne-Marie Slaughter’s “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All” was an instant sensation, attracting 1.7 million visitors to The Atlantic’s website and generating an all-time high of 200,000 Facebook recommendations. Other attention getters: Kate Bolick’s “All the Single Ladies” (November 2011), an exploration of the current state of unmarried womanhood; Lori Gottlieb’s “Marry Him!” (March 2008), an argument that women should settle for Mr. So-So lest they end up like Kate Bolick; Hanna Rosin’s “The End of Men” (July/August 2010), which presented evidence that women are outstripping men in higher education and on the job market; Rosin’s self-explanatory “The Case Against Breast-Feeding” (April 2009); and Gottlieb’s “How to Land Your Kid in Therapy” (July/August 2011), an indictment of so-called helicopter parenting. These stories have sparked lively and sometimes anguished responses in other magazines, newspapers, and popular blogs, as well as on Facebook, over lunches, and during book-group get-togethers. Four of them have sparked book deals (for Gottlieb, Rosin, Bolick, and Slaughter), and CBS has purchased a sitcom based on Bolick’s meditation on the single life.

This summer, despite (or because of) the clichéd cover image of a toddler stuffed into a woman’s briefcase, Anne-Marie Slaughter’s “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All” was an instant sensation, attracting 1.7 million visitors to The Atlantic’s website and generating an all-time high of 200,000 Facebook recommendations. Other attention getters: Kate Bolick’s “All the Single Ladies” (November 2011), an exploration of the current state of unmarried womanhood; Lori Gottlieb’s “Marry Him!” (March 2008), an argument that women should settle for Mr. So-So lest they end up like Kate Bolick; Hanna Rosin’s “The End of Men” (July/August 2010), which presented evidence that women are outstripping men in higher education and on the job market; Rosin’s self-explanatory “The Case Against Breast-Feeding” (April 2009); and Gottlieb’s “How to Land Your Kid in Therapy” (July/August 2011), an indictment of so-called helicopter parenting. These stories have sparked lively and sometimes anguished responses in other magazines, newspapers, and popular blogs, as well as on Facebook, over lunches, and during book-group get-togethers. Four of them have sparked book deals (for Gottlieb, Rosin, Bolick, and Slaughter), and CBS has purchased a sitcom based on Bolick’s meditation on the single life.

The list above doesn’t include two of the magazine’s marquee names, columnists Caitlin Flanagan and Sandra Tsing Loh, who write almost exclusively on contemporary women’s lives. While both predated Bennet’s tenure, Loh, the author of Mother on Fire: A True Motherf%#$@ Story About Parenting! as well as a number of other books and plays, has come into her own as a cultural commentator since Bennet’s arrival, turning out marvelously funny and shockingly candid pieces on everything from (resentfully) caring for an aging parent to her own divorce. Flanagan, for her part, is infamous for approvingly invoking the days when a woman had sex with her husband whether she wanted to or not (“The Wifely Duty”) and for opining that “when a mother works, something is lost.”

Clearly, a contrarian reflex is at work here, and it isn’t unique to The Atlantic’s sex-marriage-mommy pieces. The magazine so routinely reaches for the “you won’t believe this!” angle that McSweeney’s recently published a parody entitled “Counter-Intuitive Cover Stories in The Atlantic Magazine.” The list begins with “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” and “Is Facebook Making Us Lonely?” (both actual Atlantic cover lines) and proceeds to “Are Houses Making Us Homeless?” and “Are Paperweights Making Our Papers Fly Away?”

In an interview at the Aspen Ideas Festival in 2011, Bennet said that The Atlantic’s aim is “advancing constructive engagement” and making “provocative arguments on consequential questions that are relevant to our readers and our times.” Elsewhere, he uses the word “conversation” a lot. To a Washington Post reporter about the Slaughter article: “Our hope is to start the conversation.” His Editor’s Note in the issue containing “All the Single Ladies” called Bolick’s story “the latest installment in a running conversation among our writers and readers about the structural changes in the American economy, and their impact on men, women, and the family.” During an NPR interview: “Our aspiration in doing any of these pieces [on the economy and gender] is to start a conversation.”

It’s hard to blame Bennet for leaning so hard on this talking point – he probably speaks frequently in public, and why shouldn’t he want to send a consistent message? But it’s fair to ask what kinds of “conversation” The Atlantic is generating when it comes to gender issues, and whether its “provocative arguments” are in fact “advancing constructive engagement” – whether, in other words, they are enlightening rather than just entertaining its public. I’d say that the record is mixed.

Of the articles and columns that have generated the most buzz in recent years, Hanna Rosin’s “The End of Men” provided the most solid grounding for ”engagement.” Rosin is an experienced journalist, with stints at The Washington Post and The New Republic, and her article relied on detailed research and reporting. A reading of the book-length End of Men reveals Rosin as inquisitive, attuned to the story-beneath-the-story, and open to having her presumptions challenged. The End of Men may be making a very large argument – that, in terms of male-female relations, we’ve “reached the end of 200,000 years of human history” – but the book is not gratuitously provocative. Rosin suggests that workplaces, despite talk of women still not having it all, will continue to change in female-friendly ways, because women are gaining the power to make them do so. With more financial security, women are increasingly setting the ground rules when it comes to dating and marriage, holding off suitors (but not sex) until they are sure that commitment won't interfere with a secure place in the workforce. Here are hard facts that cannot help but change The Conversation. What does it mean that women now hold 51.4 percent of all managerial jobs? That within the next couple of decades they will contribute more than 50 percent of the income in the majority of married households? That the most successful U.S. companies are those that have women in top positions? That the majority of women and men, given the opportunity to control the sex of their child, would choose to have a girl rather than a boy? Rosin writes cleanly and with nuance and style, making this book likely both to get a lot of attention and to sharpen our understanding.

Kate Bolick’s “All the Single Ladies” uses Rosin’s findings to inform a more personal story about the reasons that, at 39, she had not (yet, at least) chosen to marry. It’s a wide-ranging piece, bouncing from history to demographics to anthropology, from an African-American neighborhood in Pittsburgh to an Amsterdam single-women-only apartment complex. Bolick’s reporting illuminates her autobiography, and her autobiography illuminates her reporting. She describes breaking up, in her late twenties, with her boyfriend of three years, a decision informed by “a post-Boomer ideology that values emotional fulfillment above all else.” Nothing was particularly wrong with her boyfriend or with the relationship; there was simply the feeling that “something was missing,” Bolick “wasn’t ready to settle down.” At the time, she was sure that there would be plenty of time to choose another mate. A decade later, she’s discovered that this isn’t the case. But “All the Single Ladies” is devoid of the hand wringing and obsessive second-guessing that often accompany pieces on singlehood. Bolick is comfortable with the idea that she may never have children, and while she still expresses an abstract interest in marrying one day, it doesn’t seem as if she’ll be especially rattled if that doesn’t come to pass. That her article sparked so much interest, and led to book and network TV deals suggests that many single women today are either equally sanguine, or ready for a model for becoming so.

On the other end of the reportorial spectrum from Bolick and Rosin are Caitlin Flanagan and Sandra Tsing Loh. I will say that as soon as The Atlantic arrives in my mailbox (I have been a subscriber for many years), I immediately look to see if Flanagan or Loh has a column inside. I will likely read the Flanagan first, because I need to know how much she’s going to piss me off (or, with equal likelihood, make me nod in startled, guilty, agreement) and because her prose style goes down just a bit more easily, like a smooth vodka. Her choice of topics, or at least her treatment of them, has grown narrower lately (Alec Baldwin rather than oral sex; Joan Didion rather than relations between working women and their nannies), but she is never dull.

Once I’ve dispatched Flanagan (and more on her in a moment), it’s Loh who delivers the goods. This woman is so out there — so honestly emotionally messy, so wonderfully observant about what it’s like to be a wife, mother, and daughter today. From her March 2012 article on being responsible for her increasingly aged and enduringly ornery father:

Recently a colleague at my radio station asked me, in the most cursory way, as we were waiting for the coffee to finish brewing, how I was. To my surprise, in a motion as automatic as the reflex of a mussel being poked, my body bent double and I heard myself screaming:

“I WAAAAAAAANT MY FATHERRRRRR TO DIEEEEE!!!”

Startled, and subtly stepping back to put a bit more distance between us, my co-worker asked what I meant.

“What I mean, Rob, is that even if, while howling like a banshee, I tore my 91-year-old father limb from limb with my own hands in the town square, I believe no jury of my peers would convict me. Indeed, if they knew all the facts, I believe any group of sensible, sane individuals would actually roll up their shirtsleeves and pitch in.

What, er, balls! My parents are in their seventies and quite healthy, knock wood, but reading Loh’s piece, I feel that when sickness and deep old age finally visit them, and I fail in ways large and small to be the Ur-Nurturer of my ideals, I have in effect been pre-forgiven. Loh was there before me, screaming in the coffee nook.

More somber, and even more naked, was Loh’s July/August 2009 column on the contradictions of contemporary marriage, “Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off”:

Sadly, and to my horror, I am divorcing. This was a 20-year partnership. My husband is a good man, though he did travel 20 weeks a year for work. I am a 47-year-old woman whose commitment to monogamy, at the very end, came unglued. This turn of events was a surprise. I don’t generally even enjoy men; I had an entirely manageable life and planned to go to my grave taking with me, as I do most nights to my bed, a glass of merlot and a good book. Cataclysmically changed, I disclosed everything.

Loh often discusses books related to her column topics, and sometimes she tosses in a reference to a study or two, but research isn’t really what she’s about. Rather, God bless her, she writes straight out of her own quirky intelligence and heart, and makes no pretension to doing otherwise. The subtext of her pieces is: This is what it looks like to me, and maybe some of my friends. If you relate, welcome to the club. If you don’t — hey, turn the page.

One can’t say as much for Flanagan. Like many of her readers, I have a love-hate relationship with her writing. Flanagan is undeniably witty and, at times, quite sensitive. Many of her Atlantic pieces have been somewhat reworked and folded into two books,To Hell With All That: Loving and Loathing Our Inner Housewife and Girl Land. The latter focuses on the transition, in earlier decades and today, from preadolescence to young womanhood. As the mother of a 14-year-old girl, I found this passage clear-sighted and moving:

The teenager is entering new territory and her parents cannot accompany her on the journey. Mothers are desperate to be involved in this passage – they’ve made it themselves, of course, and they would do anything to steer their daughter the right way. It is frustrating beyond measure for them when a daughter screams, “You don’t understand, and you’ll never understand!” The mother stamps her foot in aggravation, but in this case the daughter is right: the mother doesn’t understand. She merely remembers, and memory is separate from experience.

But, as I am far from the first to point out, Flanagan is never content to stop with insight, or to label speculation as speculation; she must prescribe. Girl Land, which makes whistle-stops at “Dating,” “Menstruation,” “Sexual Initiation,” and “Proms,” put me into a panic for two full days. I told my husband we had to forbid our daughter to use her laptop in her room – because Flanagan said that the porn and networking sites she’d be stumbling across would teach her that society wants her to exhibit, sexualize, and degrade herself. The only things a girl should be doing alone in her room, Flanagan instructed, are daydreaming and writing in her diary. It took me another couple of days to re-realize (it’s not as if I hadn’t thought about all this before) that access to pornography and saturation in sexualized media images are realities the younger generation is going to have to come to terms with; banning teens’ private use of laptops will not stem the onslaught. By the way, Flanagan herself has only sons, not daughters, and although I am sure she is correct that Facebook extends the day of gossip and status jockeying for many girls, you have to know your own girl and her group. My daughter and her friends seem to use it almost exclusively as a forum for complimenting each other’s ever-changing hairstyles and passing on links to goofy videos.

What readers rightly object to in Flanagan’s work is that the occasional penetrating insight is more often than not blown up into a baseless and sweeping generalization, which in turn is used as an excuse for finger wagging. “Every little girl has spent hours factoring romance and boyfriends and sweetly dressed babies into her future” (from Girl Land). Well, actually, no. “Romance” seemed equally ersatz and commercial to me at eight, 13, and 17, and babies I didn’t imagine at all. Even if I was an outlier, my experience puts the lie to “every little girl.” The overarching premise of Girl Land is that the becoming-a-teen girl “is mourning the loss of her little girlhood, in a way that boys typically don’t mourn the loss of their childhoods.” This was clearly the case for Caitlin Flanagan, who is nearly exactly my age (she was born in 1961, I in 1963). It couldn’t have been farther from the truth for me. I was actually quite excited about puberty and its various distractions, and not at all sentimental about my cute-kitten posters or other features of my premenstrual existence. I’d have to poll my old friends and classmates to get a grip on whether I was unusual, but actually talking to other people is not something Flanagan herself ever bothers to do: she just knows. If she would pull a Loh and say: “Here I am – you decide!” there would be no issue; the problem is that Flanagan says, “Here you are.”

I see some of the same tendencies in Lori Gottlieb’s work. Like her Atlantic colleagues, Gottlieb is engaging and very readable. The original magazine piece “Marry Him” was, unobjectionably, highly personal and anecdotal. It also generalized rather wildly, suggesting that women in their mid- to late thirties often dump men for reasons such as “He wants me to move downtown, but I love my home at the beach” and “Can I really spend my life with someone who’s allergic to dogs?” Furthermore, according to Gottlieb, never-married women suffer from a compulsive tendency to “hold out for someone better.” It’s pretty clear from the article that it is Gottlieb herself who has severed relationships over fairly superficial considerations and that it is she who is always secretly hoping for “someone better.” Isn’t it possible that other women end up single for very different reasons: demographics, temperament, or a lack of interest in having children?

The book-length version of “Marry Him” falls even deeper into what I might call the Flanagan Fallacy of seeing one’s own face in the face of every woman in the crowd. Here, Gottlieb has added a scaffolding of “experts” (professional matchmakers, dating coaches, psychologists, and researchers), which sometimes makes her forget that a never-married woman in her thirties is the exception, not the rule (she herself tells us that only a quarter of women younger than 34 have never tied the knot). Gottlieb again and again describes women as too picky, over-critical, and romance-obsessed to land a mate: “Too often in dating we expect to be given a lot of things from men — constant compliments, vacations, meals, 24/7 emotional support, romantic gestures.” We do? Admittedly, unlike Flanagan, Gottlieb never uses pesky terms like “all women” or “every woman,” but the implication is often there.

In her cover story “How to Land Your Kid in Therapy,” Gottlieb projects certain acknowledged personal worries, in this case about mothering (she has one child), onto a wider screen. Here is a case in which the use of “experts” shades into the pernicious. Gottlieb, who has a degree in clinical psychology, writes that numbers of her patients in their twenties and early thirties “reported that they. . .suffered from depression and anxiety, had difficulty choosing or committing to a satisfying career path, struggled with relationships, and just generally felt a sense of emptiness or lack of purpose.” In graduate school Gottlieb was taught that patients with such symptoms generally had abusive or neglectful parents, and yet this did not seem to be the case with her clients — far from it. She came to the conclusion that her clients’ parents were, if anything, too attentive, too sensitive; they tried to anticipate every want and buffer their children's every hurt, eventually making them incapable of handling life’s ordinary imperfections.

To bolster this hypothesis, Gottlieb quotes a variety of authors who have written books about youth and child rearing with titles like The Narcissism Epidemic, The Price of Privilege, Generation Me, and Too Much of a Good Thing. These authors have become authorities, in the public’s mind and in Gottlieb’s, by having a clinical practice or an academic post, or both. I am highly suspicious of the idea that either seeing patients or teaching at a university gives one a vatic wisdom when it comes to the famously complex topics of love, sex, and children, and my skepticism increased when I read some of the quotes in Gottlieb’s article. Dan Kindlon, the author of Too Much of a Good Thing, tells Gottlieb that by the time children of indulgent parents are teenagers, “they have no experience with hardship.” A professor of social theory, Barry Schwartz, claims, “Most parents tell kids, `You can do anything you want, you can quit any time, you can try this other thing if you’re not 100 percent satisfied with the other.’” Jean Twenge, who wrote The Narcissism Epidemic, chimes in that today’s parents are creating young adults who “don’t know how to work on teams or deal with limits. They get into the workplace and expect to be stimulated all the time.”

I took some time to check out what Kindlon, Schwartz, and Twenge, as well as Madeline Levine and Wendy Mogel, two other authors Gottlieb quotes, base their commentary on. Schwartz, as far as I can tell, has devoted his career to research and writing on the process of decision making, which doesn’t necessarily make him an authority on changes in parenting practices over time. Dan Kindlon seems largely to reference a 2000 survey he did of nine schools of “upper-middle to upper socioeconomic status,” along with questionnaires filled out by about 1,100 parents and 650 teenagers, followed by 50 “in-depth interviews.” This data is surely not worthless – it probably revealed many interesting things – but it doesn’t make Kindlon’s comments on generational change infallible or even necessarily persuasive. Where is his control group of respondents from, say, 1965? Wendy Mogel draws entirely from her clinical practice, and Madeline Levine from her (mostly past) clinical practice and work as a teacher and school consultant. Jean Twenge is the only one of the group who has done research into generational change: She has combed decades of archives to compare cohorts and winnow out confounding factors when it comes to self-esteem, depression and anxiety, attitudes on sex and gender, and so on. The material in her book Generation Me is intriguing, carefully couched, and, frankly, not that earth-shattering. But when a magazine writer gets her on the phone, it seems that Twenge is prone to overstatement.

I’m not in any way arguing that parenting practices have not changed in the past 30 years. We live in a world of car seats and bike helmets and over-the-top birthday parties for 5-year-olds. We’ve got parents competing to give their kids’ science-fair posters the best production values and getting way too involved in college applications. Like Gottlieb, I’ve rolled my eyes at end-of-sports-season ceremonies in which every kid gets a trophy for participation. This past year, my younger child’s middle school gave out hundreds – literally hundreds – of awards for “academic excellence.” This is all very, very stupid. But it does not follow that these practices “ruin” our kids, as the cover come-on for Gottlieb’s article suggested (“How the Cult of Self-Esteem Is Ruining Our Kids”). That is an entirely different proposition. To determine that, we’d need some very serious data, but better (and much simpler), I think, would be just to use our own powers of observation and our common sense. What follows is my own highly selective, non-authoritative, and anecdotal evidence that Kindlon, Levine, Mogel, et al., are being way hysterical. My experience won’t prove that they’re wrong – but I’d like to open up the possibility that they might be.

For the past 15 years, since my first child was several months old, I’ve lived in a middle-to-upper-middle-class suburb in the famously permissive Northeast, so I’ve been able to watch a whole cohort of kids move from infancy to adolescence. While most parents I know are more involved-slash-meddling than we remember our own parents being, we are not spineless saps who let our children “quit any time” or “try this other thing if you’re not 100 percent satisfied.” (I’ve heard far more stories of kids being scolded and cajoled to continue piano lessons or soccer until, years down the line, their utter misery forces a parental surrender.) With all due respect to Jean Twenge, the deep boredom that school generates at least some of the time surely habituates children to the experience of non-stimulation. And even when parents want to protect their children, life offers more than enough opportunities for offspring to fail, get hurt, and simply feel damn lousy. Dan Kindlon needn’t worry: By the time most kids are 16 or 17, they’ve experienced something fairly awful. Parental divorce is among the possibilities. The primary breadwinner in the family may lose a job or suffer a serious illness. A sibling or friend may die – or a beloved grandparent. I’ve seen all of these things happen repeatedly to children in our neighborhood circle. Even bracketing major life events, does anyone really think that any boy or girl who has reached the age of 14 has been spared at least one truly terrible incident, such as being suddenly and thoroughly ostracized by his or her former friends? Or failing an important class, or being bullied or shamed or beaten up? If Gottlieb et al. think we parents can prevent middle school from happening to our children, they seriously overestimate our omnipresence and power.

I’m going on at such length because “How to Land Your Kid in Therapy” is a classic example of a perverse and pervasive type of journalism, to which even the venerableAtlantic is not immune: Fact A Seems Like It Should Lead to Effect B … Therefore It Must. Anyone who has worked as a magazine writer or editor knows you can always find “experts” to bolster a supposedly counterintuitive but actually fairly trendy point of view. A serious flaw of such articles is their complete lack of historical perspective. People in their twenties or thirties (especially those who have self-selected for therapy) having difficulty choosing a career or struggling with relationships? Who could have imagined?

The developmental psychologist Erik Erikson famously said that the aim of a human life is to find fulfillment in love and work. A society with as much freedom and affluence as ours is bound to leave young people with a lot of painful questions and uncertainties. When you live on a farm where physical labor is demanded from five in the morning until nine at night and you have a passel of kids by the age of 26, you’re too busy and definitely too tired to ask yourself if this job is really the right one for you, or that guy is the one you really want to be with. The kinds of difficulties Gottlieb’s patients report are existential difficulties. They have existed for millennia. They have their basis in very worthy questions: Who am I? What has meaning? Do I matter? Am I loved? Can I love others?We see more evidence of them now not because of overindulgent parenting but because, unlike most human beings in most eras of history, young people have the leisure to experience them and the motivation and financial resources to explore them.

It’s also worth mentioning that every generation since Abraham has found its children self-centered and incomprehensible. (Horace, born 65 B.C., wrote of the following “tiresome” type of individual: “a praiser of the times that were when he was a boy, a castigator and censor of the young generation.”) Here I will again offer in rebuttal the possibly skewed study sample of my teenage children and their friends. If anything, they are a more admirable crew than my peers and I were 30-some years ago. They do more community service, they are more able to work in groups (today’s reigning pedagogies push this), and I’ve been surprised by how genuinely they accept “difference” in their social worlds – disabilities, other ethnicities, gay parents, emotional problems – just as they’ve been schooled to do. Good sportsmanship is an ideal among them, if not always achieved. Are they sometimes self-absorbed, rude, and entitled? Sure. They’re teenagers! The oldest of my nieces and nephews are now 25 and 22. When they were small fry, my husband and I used to wonder if the great affluence in which they grew up would spoil them. Since graduating from college, the elder has been working in the community-health sector, assisting with research into HIV, childhood obesity, and other public-health scourges. The younger threw himself into Obama’s 2008 political campaign, spent summers on the Hill, and is currently looking for a job in environmental policy. Narcissists? I don’t think so.

But in the world of magazine cover stories, the sky must always be falling (Facebook is making us lonely! Google is making us stupid!). Here we come full circle to Anne-Marie Slaughter and “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All.” Just as “How to Land Your Kid in Therapy” overlooked the fact that “a sense of emptiness” is a built-in human vulnerability, Slaughter’s piece suffers from a rather startling failure to recognize the laws of physics. Lori Gottlieb herself, interestingly enough, points this out in one of the many responses published on The Atlantic’s website. Slaughter’s article, she wrote, wasn’t really about women in the workplace; it was about how Slaughter, then a senior State Department official, couldn’t be in Princeton and Washington, D.C., at the same time.

Slaughter’s stated intention was to show that even the most powerful, talented, and ambitious women butt up against workplace rigidities that cause them to drop out. That is a point worth discussing, and without question there are many problems with the status quo. But a rigid workplace is not really why Anne-Marie Slaughter ended up quitting her State Department job. By her own testimony, she left that job because she had a 14-year-old son in New Jersey with behavioral problems. No flexible working arrangements would have made it possible not to be in the nation’s capital, 200 miles from home, for an extremely demanding government position, or to have 36 rather than 24 hours in the day. Slaughter even had a husband whose schedule allowed him to be “the wife” much of the time (and presumably some outside help, although she doesn’t mention it specifically). There are certain jobs that simply don’t work for certain people at certain times in their lives.

But by giving the article the title “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” Slaughter, or her editors, cannily marketed the piece as a contribution to feminist debates stretching back over decades. And here I need to take a slight detour into the sad fate, in The Atlantic, of this oh-so-simple yet much-abused and misused term: feminism. Slaughter invokes it. Gottlieb invokes it. Flanagan and Bolick invoke it. Slaughter:

For the remainder of my stint in Washington, I was increasingly aware that the feminist beliefs on which I had built my entire career were shifting under my feet.

Gottlieb:

To the outside world, of course, [single women] still call ourselves feminists and insist – vehemently, even – that we’re independent and self-sufficient and don’t believe in any of that damsel-in-distress stuff, but in reality, we aren’t fish who can do without a bicycle, we’re women who want a traditional family.

Bolick:

The elevation of independence over coupling […] is a second-wave feminist idea I’d acquired from my mother, who had embraced it, in part, I suspect, to correct for her own choices.

As for Flanagan, let me sum up her stance by noting that on a 2006 segment of The Colbert Report, she described herself as “vehemently” critical of the modern feminist movement and revealed that her original title for To Hell With All That was How Feminism Short-Changed a Generation.

Now, let’s look at the definition of the term “feminism” and think about the possible responsibilities of a magazine like The Atlantic when its writers invoke it. According to the Oxford English Dictionary: “belief in the social, political, and economic equality of the sexes.” Or, if you prefer Wikipedia (I do): “a collection of movements aimed at defining, establishing, and defending equal political, economic, and social rights for women.”

But when many of The Atlantic writers use the words feminist or feminism (I except Loh, who seems to have read her women’s movement history, and Rosin, who mostly avoids the terms), they are using them in the debased, wholly inaccurate sense of “people who promised that I wouldn’t run into agonizing conflicts between the health of my children and my career” (Slaughter) or “ideology that says women don’t desire and need men or that being single is morally superior to marriage” (Gottlieb and Bolick). Where are the editorial pencils addressing this sloppiness, this kind of not-thinking? I don’t believe thatThe Atlantic editors don’t know any better. I think they realize there’s more potential buzz in an article that seems to be contra something – contra, in this case, what “feminism” has “promised” us or “told” us to do or choose or believe. Flanagan achieves her frissons by positing herself as the heroic warrior against feminism’s constricting ideals (equal political, economic, and social rights for women! Slay those dragons, Caitlin!), Gottlieb by telling women they have to “get over themselves” (with the implication that feminism has “taught” women to expect too much), Slaughter by being terribly disappointed that those feminists just didn’t come through for us yet again.

If you visit the website for an organization called VIDA, you can see the results of itsannual surveys, which track the number of major magazine pieces published annually by men versus women. All that can be said about the truly discouraging numbers is that they put The Atlantic in a slightly better light. I am a compulsive magazine subscriber and reader, but before learning about VIDA I had utterly failed to register that male writers in magazines from Harper’s to The New Yorker to The New York Review of Books still often outnumber women writers by three to one. I don’t claim to know why this is so, but clearly something is very wrong. In this context, I’m grateful that The Atlantic has given quality real estate to Rosin, Bolick, et al., in recent years. If its numbers overall are still badly skewed, if eight of its nine bloggers are men, well, these are things for it to work on. Maybe The Atlantic’s editors should be trying a whole lot harder to find more women to write stories on politics and the economy.

¤

Generally, I think there’s nothing so very wicked about the “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All” or even the “How to Land Your Kid in Therapy” kinds of stories. At worst, I tell myself, they lead to bloviating and unnecessary anxiety. At other times, I wonder. For sure, when The Atlantic runs broad-brush trend stories on its cover or gives over column after column to writers who generalize and preach, it’s not doing much more than generating website hits and selling copies. But constructive engagement requires a deeper kind of thinking. Among other things, it means fighting the temptation to describe My Problem as Everyone’s Problem or to trumpet significant changes in social behavior or human consciousness where these just don’t exist. Promoting “big ideas” via shaky expert commentary or received wisdom or cleverly turned phrases can contribute to the degradation of serious public discourse. Self-appointed shepherds of that discourse have a responsibility to encourage humility and scrupulousness. There was a time when the experts “knew” that autism was caused by emotionally withholding mothers, that up to 90 percent of women were sexually frigid, that mothers who didn’t “bond” with their infants in the first hour after birth would have emotionally damaged children. Magazine articles were written based on the research and self-confident pronouncements of those experts, and they look pretty blindered and ridiculous now. Let The Atlantic, with its stated interest in furthering the gender conversation, look to posterity as much as to its sales numbers.

More Los Angeles Review of Books

-

Reading in prison

"The Art of War" as survival guide -

Andi Zeisler on "The Good Girls' Revolt"

Power suit: Dissent in the newsroom

Shares