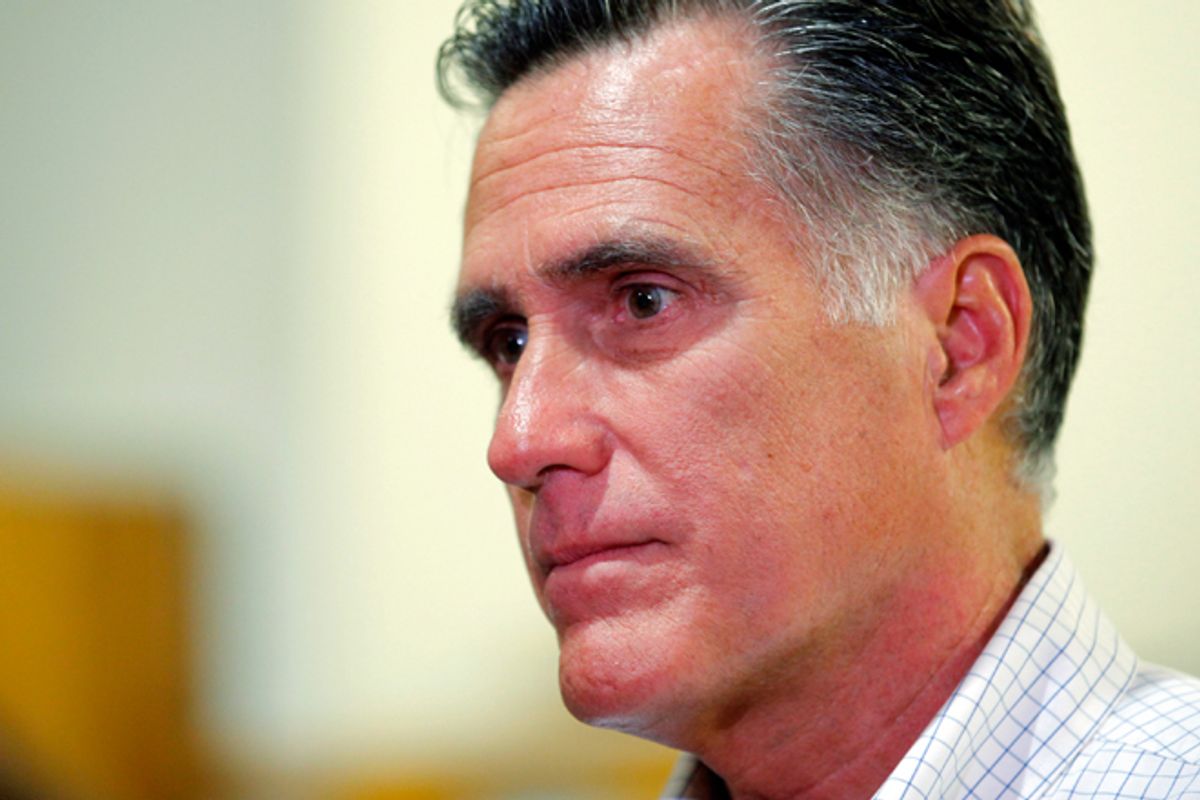

After what, by almost any measure, has to have been the worst week yet for Romney and Ryan -- a botched convention, disappointing polls and an amazing inability to articulate a clear message about their own agenda -- it seems a little odd to speculate on what a Mitt Romney presidency would look like. Nevertheless, hope springs eternal: Opinion pieces published today in both the Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg take a stab at envisioning the Romney era. Let's combine the two and see what happens!

In the Journal, Eric Convey, a former Boston journalist, tells us that the best predictor of how Romney will govern can be found in his four years as Massachusetts governor, a period "replete with examples of ways the management-consultant-turned-investor brought his private-sector sensibilities to his public responsibilities."

He'll stock his cabinet with business executives, rely on outside consultants for policy analysis, and "it's a safe bet that defenders of government spending from both parties will have to bolster their data with well-founded economic arguments if they want him to stay his hand."

There will, of course, be one huge difference. As governor, Romney was forced to work with an overwhelmingly Democratic, veto-proof majority. As president, he would share power with a Congress likely controlled by extremely conservative Republicans sure to view his Massachusetts achievements as naked socialism.

In Bloomberg, Ramesh Ponnoru, who irritated Democrats last week by arguing that a second term for Obama would be essentially worthless because he wouldn't be able to push any legislation through partisan gridlock, tries to make amends by theorizing that Romney would also face huge difficulties pursuing his agenda.

Romney, writes Ponnuru, wants to cut taxes and boost defense spending, while at the same time promising not to raise the debt ceiling unless Congress agrees to a constitutional amendment limiting spending to 18 percent of the economy. Even if there was a way to make the math work on such a plan (there isn't, at least not without cutting government services so sharply that Republicans might lose power in Washington for a generation) Senate Democrats won't agree to a deal that doesn't include some tax hikes, theorizes Ponnuru, thus placing Romney in an impossible situation. Romney can bring in all the consultants he wants -- if they're sane, they'll tell him that a responsible approach to fixing government finances includes a mix of spending cuts and revenue increases. The Tea Party will not be amused.

Both of these analyses ignore an important point. Who's to say the White House would be in the driver's seat in terms of setting the policy agenda after a Romney election win? Suppose Republicans take the Senate. Even if a Democratic minority demonstrates the same appetite for filibustering that the Republicans did (which they won't), there will still be all kinds of games that congressional Republicans can play with budget reconciliation rules. It's not hard to imagine a scenario in which legislation crafted by House radicals and jammed through the Senate floods onto Romney's desk. The notion that Mitt might veto his own party's agenda seems unlikely. There will be government in a Romney presidency -- it's just not going to be good government.

Shares