I grew up Mormon, and every year I endured a hair-raising interview to get my “temple recommend.” (Think of it like Mormon “security clearance.”) It was a firewalk in the guise of an annual interrogation. Everyone in my life would know if I failed. I’d be excluded from joining my family and friends in Temple rituals. Rumors would flood my neighborhood in Utah Valley. And every year, the same question threatened to consume me with shame.

"Do you touch yourself?"

Each time I lied, I plunged into a very Mormon kind of hell.

I was not born a bad Mormon. My great-great-grandparents were among Utah's earliest Mormon pioneers. Like Mitt Romney, I have ancestors who fled to Mexico to practice polygamy after Utah outlawed it. Other ancestors were martyred during the Mormons' 1,300-mile westward trek to "Zion" in search of religious freedom. Others fought against U.S. armed forces in the 1857 Utah War to protect this freedom.

My path was also clear. From the time we're in kindergarten, Mormon boys know that when we turn 19, we'll serve a mission for the church somewhere in the big world. When adults asked my playmates and me where we wanted to serve, most of us said, "China!" Even then we knew that after we returned from our mission, we would look for a wife. Few of us would turn 23 unmarried.

But at the age of 12, one autumn afternoon in 1997, along with my cohort of 12- and 13-year-old neighbor boys, I received my first copy of “For the Strength of Youth.” We sat in a circle of metal folding chairs in our Sunday school classroom and each of us read aloud a section from the pamphlet. My turn came:

The Lord specifically forbids certain behaviors, including all sexual relations before marriage, petting, sex perversion (such as homosexuality, rape, and incest), masturbation, or preoccupation with sex in thought, speech, or action. Homosexual and lesbian activities are sinful and an abomination to the Lord.

I read the last sentence in a croaky whisper.

As if the point weren't clear enough, my Sunday school teacher hammered it home by explaining that sexual sins were among the most grievous, and as proof cited a passage from the Book of Mormon:

Know ye not, my son, that these things are an abomination in the sight of the Lord; yea, most abominable above all sins save it be the shedding of innocent blood or denying the Holy Ghost?

Until that autumn afternoon, I'd thought of myself as a good kid. I didn't cheat in school. I seldom lied. I never stole so much as an extra Tootsie Roll from an unguarded bowl of Halloween candy. (In my neighborhood, older folks who didn't stay up late could leave Halloween treats by their doorsteps without worrying that a trick-or-treater might grab more than his or her fair share.)

“For the Strength of Youth,” however, said I was guilty of a sin far worse than lying, cheating, or candy stealing. My sin was only a little less severe than murder. And I sometimes did it twice daily. And my close calls with spiritual homicide involved lurid imaginings of Bruce Willis and, of all people, Dan Lauria from “The Wonder Years.”

I walked into that Sunday school lesson a light-hearted Mormon boy, and I walked out of it a very unhappy young man, but one possessed by the resolve -- the determination -- to move forward no matter how high the cost. I was a grizzled Mormon pioneer.

I spent no time complaining. I didn't ask why God had saddled me with seemingly impossible circumstances. I got to work. I kept “For the Strength of Youth” beside my bed. I read from it on long nights when I lie awake alone in my room listening to the clock tick, my squirmy adolescent body denying me any sleep.

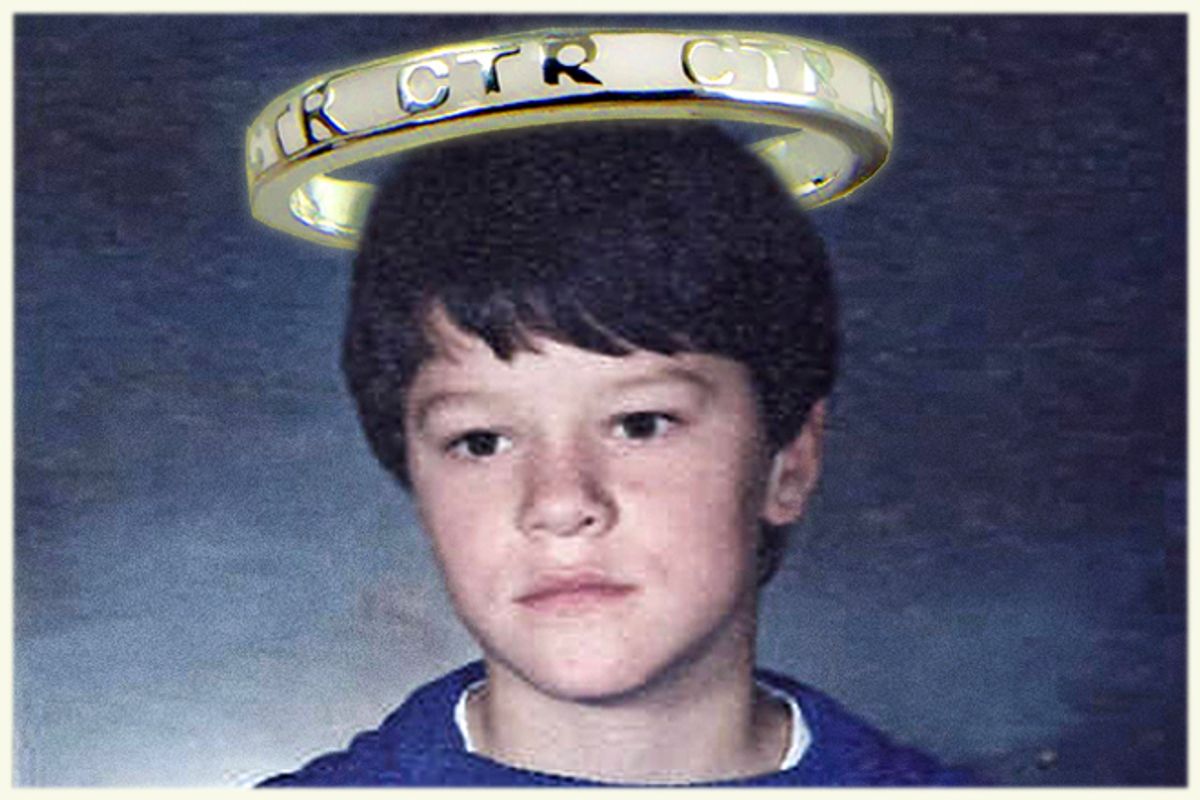

To stay my hand, I convinced my mother to take me to our local branch of Deseret Book, a church-owned chain, and buy me a thick silver ring decorated with a shield emblazoned with the letters "CTR," meaning "Choose the Right." When temptation haunted me, I twisted the ring until the skin beneath chaffed and bled.

I also kept a record of my progress on a calendar I had squirreled away in my nightstand. On days when I managed to refrain from touching myself, I awarded myself a star. But according to popular Mormon belief, if you repent of a specific sin and then repeat it, all your previous sins return to weigh on your conscience. My calendar's pages didn't shine like the Milky Way. They were filled with black holes.

A few months into my experiment in the astronomy of chasteness, my Sunday school teacher announced that, for the first time, I would join my fellow young men on a trip to the temple to perform baptisms for the dead, one of Mormonism's most sacred and, for better or worse, distinctive rituals. To give dead non-Mormons a last-chance, take-it-or-leave-it opportunity to convert to Mormonism and secure a place in the Mormon hereafter, a volunteer would immerse himself in the baptismal font's cozy water while pronouncing or, more often, horribly mispronouncing the earthly name of some lucky non-Mormon soul, choosing at random from one or another far-flung corner of the world.

In order to save legions of imperiled non-Mormon souls and demonstrate beyond doubt the purity of my own soul, I had to ace the worthiness interview.

On the Saturday morning of our trip to the temple, I dressed in my Sunday clothes -- my no-iron white shirt, my no-iron black slacks, my red-and-blue-striped clip-on tie -- and made my way to the empty church classroom where my bishop waited to kindly, patiently, methodically grill me about the most intimate aspects of my private life.

Rather than make eye contact with my bishop, I preferred to study the framed print hanging on the wall behind him: a colorful painting of Christ preaching atop a Mayan pyramid to a throng of rapt listeners.

"Do you keep the Law of Chastity?" my bishop asked.

"Yes." I worried that I answered too quickly.

"Have you engaged in any sexual activity with others?"

"No."

"Do you touch yourself?"

"No."

Satisfied, my bishop filled out my temple recommend card, a slip of stiff paper that stated my name, gender, age, and the temple rituals I was allowed to perform (indicated by a checked box next to the words "baptism for dead only.") He handed me the card to sign. I signed it with my sweaty little hand.

I stepped into the hallway where the other boys were waiting to do their interviews. They marveled at my temple recommend. I tucked it into its plastic protector and sat silently until we left for the temple.

As we entered the chilly white-granite building, I expected that the sweet granny volunteering at the front desk would detect my imposture and call security to perp-walk me off the premises. After all, the people I most loved and respected had taught me that God would never allow His temples to be violated. Surely, the pious little grannies volunteering at the temple had a godly knack for separating chaste sheep from randy, impure goats.

Yet somehow I -- a randy, impure adolescent goat -- managed to fool the grannies, and myself. My shame and self-disgust convinced me I was the only adolescent boy in Mormon history to have first-hand knowledge of a great orgasm.

My secret knowledge made me sometimes want to kill myself.

As I lied and lied in my annual worthiness interviews, my fear grew exponentially. When my aunt had a mastectomy, I was relieved to think of my sin like a cancer, something that could be cut out of me. I was so addled that I found it soothing to think that if I worked hard enough and long enough at part-time jobs, I could to give myself a secret present on my 18th birthday: surgical castration.

This weirdly mechanical solution, this idea of my body as a machine vulnerable to sabotage, was inspired by a famous talk on puberty and procreation that was given by General Authority Boyd K. Packer in 1976, and later published as a pamphlet and routinely given to Mormon boys everywhere.

Packer began his talk by likening the male reproductive system to a "little factory" that manufactures a "life-giving substance":

For the most part, unless you tamper with [your little factory,] you will hardly be aware that it is working at all.

After matter-of-factly covering various "release valves" and their care and maintenance, Packer ventured into a hair-raising prognosis. A young man who fiddles with his release valves is a young man who dooms himself to doing so again and again:

This you should not do, for if you do that, the little factory will speed up ... You can quickly be subjected to a habit, one that is not worthy, one that will leave you feeling depressed and feeling guilty ... Keep it in reserve for the time when it can be righteously employed.

In this context, my castration plan wasn't unreasonable. It was a practical way for me to serve my mission, to share a bedroom with other young missionaries, without betraying my sin to my church, my family, my friends, my neighborhood, the whole Mormon world at large.

And who knows what might have happened if I had stayed on that path. I might be married now, or I might be a Mandarin-speaking eunuch. But instead, I came across Andy Warhol's silkscreen of Marilyn Monroe in a high-school art textbook.

Other apostates might find their epiphany in jazz, punk rock or abstract expressionism. For me, Pop Art highlighted what was exaggerated in the mundane. My first glimpse of Andy Warhol made me begin to look at my life -- and my surroundings -- in a startling new way. It gave me the distance necessary to see that what I considered normal and everyday was suffused with unnatural color and unreal appearances.

Something seen can't be unseen.

Subverted by Warhol's Marilyn, I gobbled up Anthony Burgess's "A Clockwork Orange" before I was old enough to rent the movie. I bought Sonic Youth records and listened to them late into my starless nights, filled with a growing sense that in order for me to shoehorn myself into Utah Valley and Mormon life, castration would be insufficient. I'd have to have my brain surgically removed.

I reached the point of do or die.

When I was 17 years old, I chose, like my Mormon ancestors, "do" over "die." Would they have expected anything less of me?

I walked away from all that was everyday and commonplace. I walked away from Utah Valley, family, friends, and everything that was lovingly, or otherwise, familiar. I headed into a world for which my previous life had never prepared me -- a degree in secular, foreign literatures and romances of my own choosing.

The Church has changed since my days. It has tried to update and soften its teachings on masturbation, issuing new versions of its literature for youth with slightly less condemning language, but it cannot help the culture of shame and denial embedded inside the faith (for instance, Packer's pamphlet about little factories and release valves is still distributed on the Church's website.)

Blogs like The Mormon Therapist offer regular challenges to these aspects of the Church's doctrine, which I watch from the sidelines, glad that there are still people with the patience, faith and resolve to change it from within.

But all of that is in my rear-view mirror now.

While making my way to my own private Zion, I heard a song by Michelle Shocked, another Mormon who walked away, but whose lyrics I think my Mormon ancestors would have appreciated:

What the hell'd you let them break your spirit for?

You know, their lives ran in circles so small.

Ah, they thought they'd seen it all.

And they could not make a place for a girl who'd seen the ocean.

I had seen the ocean, and I wasn't going back to the desert ever again.

Shares