Everyone knows that Damien Echols has a remarkable, chilling story to tell. As the most visible member of the West Memphis Three, he spent 18 years (half his life) on death row for a crime he did not commit. With two teenage friends, Echols was convicted in 1994 for the murders of three little boys in the Robin Hood Hills area of West Memphis, Ark. Their case gained national attention as the subject of the documentary film "Paradise Lost" by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky. The film, the first of a series of three made for HBO, scrutinized the flimsiness of the evidence against the three young men and won them widespread support from the public and assorted celebrities. All three were released from prison last year in a complex plea agreement.

However, few people know, and many are about to discover, that Echols is a writer whose talent is commensurate with the task of telling this story. The fiercely personal aura of a purloined diary clings to his new memoir, "Life After Death," and the underwhelming response to an earlier, self-published version of his life story suggests that his editor, Sarah Hochman, played a significant role in whipping the book into shape. But the raw materials are there. Now, fortunately, Echols has the chance to see what he can do with them.

"Life After Death" alternates between the narrative of Echols' first 18 years in small, scruffy West Memphis and a present-tense account of his life on death row. A moody, intelligent and metaphysically inclined boy, Echols grew up in rural poverty and surrounded by harsh, revival-tent piety. His parents split up when Echols was in the third grade, and his mother married an abusive older man who eventually adopted her two children and insisted on being called "Dad." They all lived in an isolated, four-room shack, "with no running water or electricity to speak of, no heat or air conditioner and half the front porch caved in on itself." Damien read a lot of Stephen King and listened to hair bands. He also converted to Catholicism because the religion spoke to his aesthetic and mystical yearnings.

Echols had long (naturally) black hair, wore black clothes and collected animal skulls -- all behaviors that former disgruntled teenage misfits recognize as fairly typical (and harmless) expressions of the disgruntled teenage misfit point of view. A county juvenile law enforcement officer, Jerry Driver, however, saw things differently. Obsessed with the delusional belief that the area was rife with bloodthirsty satanic cults, he harassed Echols, whom he pegged as a leader of the cults, and his friends. Echols fell into Driver's clutches when, while running away with a girlfriend, he broke into an abandoned trailer. Driver persuaded Echols and his parents that the only way to save the boy from nine months awaiting trial in county jail would be to check him into a mental institution.

The only direct evidence against Echols and his best friend, Jason Baldwin, in the 1992 murders was a confession obtained from a borderline mentally disabled acquaintance -- a confession that was obtained under highly dubious circumstances. The case against the West Memphis Three was, therefore, dependent on demonizing Echols, who was portrayed as the ringleader in a group that practiced heavy-metal-inspired ritual human sacrifice. Later, Echols' defense team would attempt to overturn the conviction by arguing that he was too ill mentally to stand trial. For these reasons, Echols' psychological health is a sensitive issue, but he downplays it in "Life After Death," portraying his two stays in mental institutions as yet more of the misguided, adult-dictated injustices he sullenly endured because he had no other option.

The Echols that comes across in the pages of "Life After Death" is not so very different from that teenager -- fuming with disillusioned disgust at everyone from his mother (a "drama queen") to the justice system and, especially, the arbitrary and often sadistic prison authorities. Of course, Echols' disgust is extremely well-founded, but it's also markedly passive and distinctly adolescent in flavor. He still sees himself as the helpless if defiant object of utterly contemptible figures and institutions in power, rather than as a disenfranchised citizen fighting to recover his rights. That's understandable -- no one's more powerless than a prisoner -- but it's not the attitude of most convicts who campaign for their own release. And, in truth, Echols' wife, Lorri Davis, seems to have been the driving force behind the legal battle to free the West Memphis Three. (When Arkansas prosecutors negotiated the men's release, one of them was heard to ask, "Is this going to get rid of Lorri Davis?")

I mean this as no knock on Echols; he entered death row as an adolescent and, for all that his sufferings have changed him, in some respects he's never had the chance to fully grow up. It's a situation that, perversely enough, makes his memoir more fascinating. One of the ironies of Echols' story is that the very interests and attitudes that made him a pariah in West Memphis aroused the sympathies of not only Davis but the musicians, actors, filmmakers and other artists who have come to his defense. Johnny Depp, Eddie Vedder, Metallica, Peter Jackson, Marilyn Manson and others have contributed funds and called attention to his plight. (And it's worth pausing here to think about how differently this story might have turned out if Echols were, like most death row inmates, merely poor and black.)

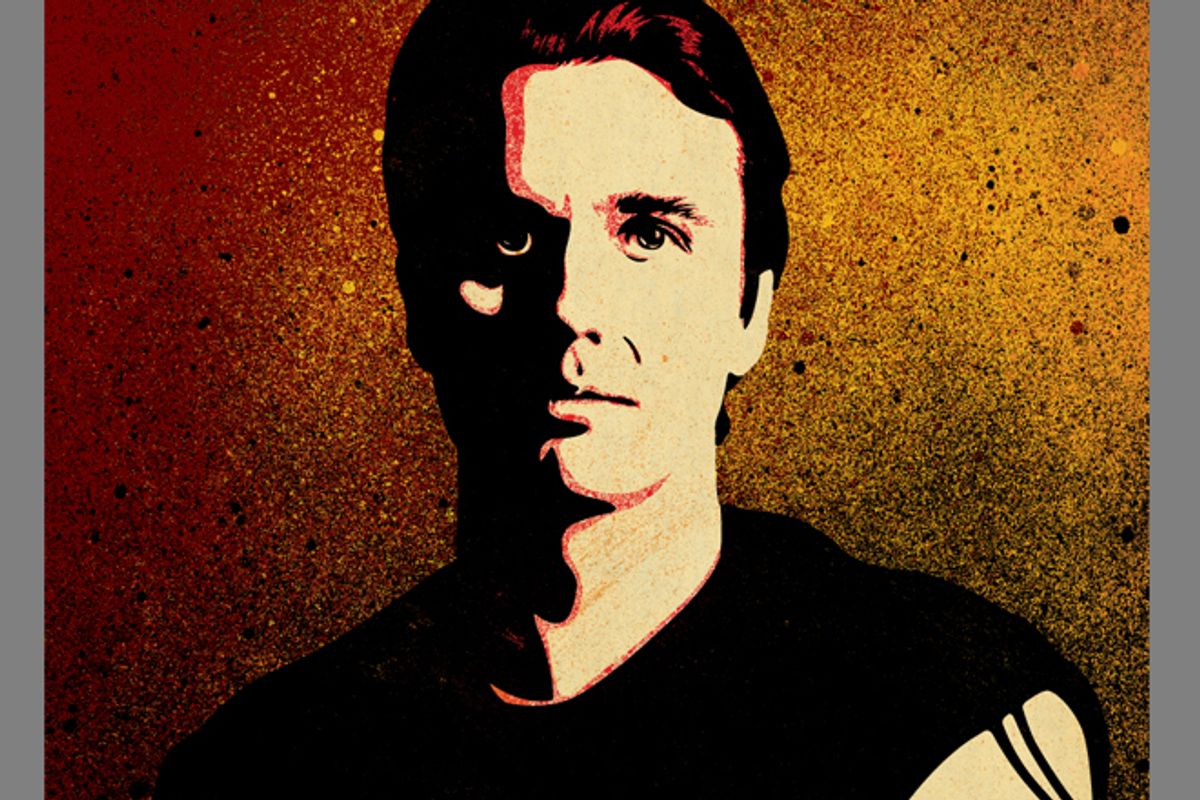

All these creative types no doubt took one look at Echols' brooding image and saw their own weird, ostracized, angry teenage selves. That same self is vividly present in "Life After Death," somewhat filtered and refined by experience and nearly two decades of intensive reading. Echols has also spent countless hours searching for and losing himself in memories of his pre-prison years, in contrast to the usual adolescent eagerness to grow up and leave it all behind. The Echols you see in the first "Paradise Lost" film is manifestly bright, but he has a hard time expressing his thoughts and feelings. The Echols of "Life After Death" is uniquely positioned to articulate that heightened, emotionally saturated and achingly desirous teenage state of mind, from the sweeping resentment to the thwarted love to the grandiose fantasies to the resentful alienation to the epic despair.

This ability becomes the most arresting aspect of "Life After Death." There are moments of florid metaphorical overkill ("Time itself has become a cruel race toward an ash-colored sunset") but there are far more that impress, especially on the subject of time. "The year, the idea of a year, has become paper-thin," Echols writes of life in prison. "I can almost reach out and tear a hole through it with my fingernail." Longing to spend Christmas beyond its walls, he imagines, "In the outside world the air would feel like a music box."

Echols' passionate love of the winter, of Charlie Brown TV specials and Guns 'N' Roses -- these are the endearingly intense, taste-based identity badges of adolescence. In "Life After Death," however, they've been protected and concentrated by a cherishing vigilance, in the same way that, while in prison, Echols refused to eat Hershey's Kisses for 11 months of the year in order to preserve their ability to remind him of December. Where bad adolescent writing is sweeping and generic, Echols has learned the power of the specific image: a prison wall black with mosquitoes, an inmate who tied perfume inset cards from magazines over his face to protect himself from his neighbor's farts, a comparison of the the health hazards of prison life to "that old video game Frogger. Sooner or later he always gets squashed. The only question is how long you can prevent it from happening."

There's not much about the 1992 murders in "Life After Death," no doubt because Echols had nothing to do with them. There's also relatively little about his trial. I picked up this memoir looking for those two things, but after a couple of chapters I never missed them. What you get instead is an unusual, indelible portrait of a fledgling soul in extremis. Echols turned out to be tougher than even he expected. The man who has emerged from death row at last is not quite a hero, but he's something far more interesting: an artist -- and, most definitely, well worth meeting.

Shares