For former Army Infantry Sergeant Sean Knapp, finding help for his addictions was a grueling, eight-year-long process. Even worse, it was one that nearly cost him, and his family, their lives.

After serving in the Army from 1994 to 2000, Knapp was honorably discharged and moved to Wisconsin, where he met and married his wife, Sharlene. It wasn’t long before the transition to civilian life, which he describes as “absolutely awful,” took a toll: Knapp sank into depression, started abusing narcotic pain pills and later turned to alcohol.

In 2007, he hit what everyone hoped was rock bottom: Knapp, brandishing a loaded gun, contained his wife and their two young children in their home while staging a four-hour standoff with police. “He was telling the police to shoot him,” Sharlene recalls. “He said he just wanted to die, but it was an obvious sign for help.”

Unfortunately, it wasn’t a sign that anyone at Veterans Affairs was paying much attention to: Despite being sent to a VA hospital, Knapp was offered little more than a once-a-week appointment with a psychologist. “It was almost like they were saying, ‘See how far you get alive, then we’ll help you,’” Sharlene says. “That they would do so little was truly incredible to us.”

Finally, when a nearly identical incident happened a year later, VA officials enrolled Knapp in an inpatient addiction treatment program. Two years and three stints in the program later, Knapp eventually kicked his habits.

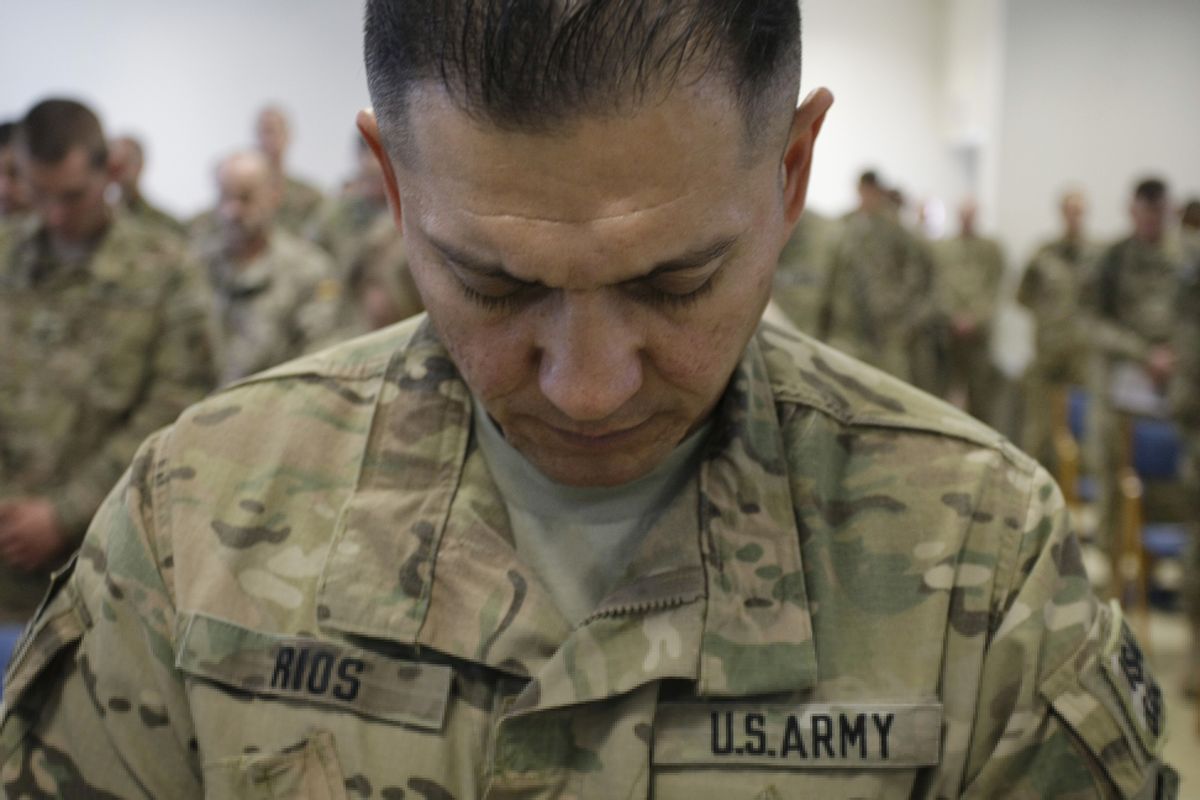

Among the thousands of soldiers and veterans who’ve coped with addiction, Knapp’s story is arguably on the extreme end of the spectrum. But it highlights a vital shortcoming concerning the military’s treatment for addiction: Care, among those willing to seek it out, has long been difficult to access and only middling successful.

And with heightened tensions across the Middle East, the situation of today's troops and veterans threatens to grow even more dire. With the increasingly less dim prospect of these latest conflicts, precipitated again last week by a deadly assault on the US embassy in Libya, escalating into yet another war, the military is poised to continue its cycle of injury, PTSD, addiction and suicides. Accompanying that, of course, will be a federal budget even more frayed, potentially unable to help the rising tide of suffering soldiers.

On paper, the military looks to have its bases covered on the treatment front. Every service branch offers both inpatient and outpatient substance abuse programs for men and women on active duty. Early this year, for example, the Pentagon reported 215 different outpatient programs across the country.

For veterans, the VA offers several types of “substance use disorder” treatment programs, from once-a-week outpatient counseling to intensive, 28-day, 24-hour residential initiatives like the one that Knapp relied on for his recovery.

But despite the seeming breadth of services to help soldiers and veterans, myriad complications and defects keep many from getting often desperately needed help: Both the military and the VA are plagued by shortages of counselors and space; access to treatment remains a challenge, whether due to stigma, bureaucracy or geography; and because soldiers and veterans often suffer from a unique complexity of mental health problems (like PTSD) and addiction, the bar for successful treatment is unusually high.

This situation is increasingly dire as the veterans from the two Gulf wars come home and attempt, against unprecedented odds, including a stalled economy, to return to civilian life. (One bright spot: In August the unemployment rate for veterans hit a three-year low, 6.9%, thanks to recently implemented Obama administration initiatives.)

“It was like they were saying, ‘See how far you get alive, then we’ll help you,’” Sharlene says.

“In many ways, addiction is a universal phenomenon,” Amy Singer, senior vice-president at New York’s Phoenix House, a rehab center that offers special programs for addicted personnel and veterans. “The challenges we’re seeing in treating military populations, though, really puts them into a category of their own.”

It’s a category that, as the military and the VA admits, continues to grow. Where alcohol abuse is concerned, for example, the military saw a 56% increase among those seeking treatment between 2003 and 2010. Data on other types of addiction is outdated, but in 2009 the VA noted that 19% of current conflict veterans who sought mental health counseling were abusing at least one substance.

“The bottom line is, we don’t have accurate numbers,” Dan Abrahamson, a director at the Drug Policy Alliance who co-authored a 2009 report on military addiction, told the Navy Times. “Veterans are just getting lost as they come back home.”

Even for soldiers and veterans who don’t get lost, the military acknowledged a lack of adequate facilities for treatment seekers. Last year, former Army Vice Chief of Staff Peter Chiarelli warned that the service urgently needed another 130 qualified counselors merely to handle the current load of substance abuse cases, which is expected to grow as more soldiers endure repeat deployments or troubled transitions to civilian life. The problem “needs to be rectified as soon as possible,” he urged.

Among veterans, the crisis may be even more severe. The VA earlier this year announced plans to hire an additional 1,900 mental health counselors to tackle health problems including PTSD, depression and substance abuse among veterans.

But as a memo from leaders at the American Psychiatric Association noted earlier this year, the move will come too late for many: Most veterans, the APA noted, suffer long wait times to access initial help, and then only see their VA psychiatrist two to three times a year “due to access demands.” A 2012 report by the Government Accountability Office found that the average wait time for evaluations and benefit for active-duty troops was close to 400 days.

In some parts of the country, such as Fort Harrison near Helena, Montana, VA clinician shortages are so severe that newly built clinics can’t even open. Officials at Fort Harrison said they can’t recruit enough staff to open a year-old, $7 million inpatient facility for veterans with mental health or substance abuse problems—forcing vets to seek help from VA clinics in other states.

“I’m very comfortable in the knowledge that even though we don’t have those programs up and running, the veterans are getting a high standard of care where we are sending them,” Robin Korogi, director of Montana’s VA healthcare system, told the Billings Gazette in March. “My number-one goal is that they get the treatment they need.”

The quality of that treatment, however, remains an open question. Because of the military’s enormous problem with substance abuse, some soldiers and veterans are referred to one of more than 1,000 civilian treatment facilities whose services are covered by TRICARE, the Pentagon’s healthcare program. But services at those facilities are so poorly supervised and audited by military officials—little more than a few pieces of paperwork are necessary to receive federal approval—that one independent investigation, by NextGov, maligned the process as less rigorous than “[what] Consumer Reports applies to the testing of toasters.”

“Trouble is, there aren’t very many senior folks in the military who understand, or care about, treatment for alcoholism,” one retired Army officer, who struggled with addiction, told the publication at the time.

Furthermore, most civilian treatment centers don’t even come close to offering the kinds of care that soldiers and veterans need. One pressing issue, according to Singer, is that most veterans would rather seek treatment from someone with military experience.

“We tried to hire individuals who were either veterans or had experience working with them,” she says of Phoenix House, which itself was founded by a former Navy psychiatrist. “In many instances, we find that a veteran feels like a community member, like they can speak freely, when they’re cared for by someone who knows, firsthand, what they’ve seen.”

Civilian rehab centers are also less likely to offer services that treat what’s often a combination of substance abuse and some other mental health problem, like PTSD, wrought from years of grueling combat and brain injuries. In fact, only eight of the civilian facilities used by the Army have the capacity for this kind of integrated treatment, according to Pentagon documents.

Admittedly, the problem of comorbidity is a treatment challenge that still vexes even clinicians working within the military and the VA. In one 2010 survey of over 200 VA clinicians, respondents noted that treating a veteran with combined PTSD and substance-use disorder was, not surprisingly, “more challenging” that treating one of the issues on its own.

PTSD is also notoriously difficult to diagnose, and some experts believe that is both underdiagnosed (for example, many active-duty soldiers hide their symptoms for fear of retribution) and overdiagnosed (for example, some may exaggerate their symptoms in order to be eligible for benefits. Leading PTSD researchers nationwide are hoping to get $50 million in federal funding to launch a long-term, large-scale trial of veterans to look for biological markers for the trauma syndrome in hopes of clarifying the diagnosis.

“In terms of systems issues, [respondents] reported frustration with a lack of integration of PTSD and substance-use disorder treatment within the VA,” the study notes. “As well as policies that sometimes decrease the quality of care.”

The frequency of addiction and PTSD, when coupled with the inadequacy of treatment, have a predictably dire result. Among the 2 million men and women who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan, suicides are rising at an unprecedented rate. In July, 26 active-duty Army soldiers were reported to have taken their own lives, a three-year monthly high. The number of active-duty suicides this year is on schedule to exceed 2011's count of 165. As for the other forces this year, the Air Force has seen 55 suicides; the Navy, 39; and the Marines, 32, according to the Army Times. The numbers are even worse for veterans, who are taking their own lives at the rate of 18 a day.

To their credit, officials with the Pentagon and the VA are taking steps to ameliorate shortcomings in substance abuse treatment—both access and quality. Among them is the Army’s introduction of financial incentives to lure highly qualified counselors, and the Navy’s groundbreaking plans to initiate random alcohol testing in addition to conventional drug screening.

Arguably most notable is an executive order, signed in late August by President Obama. The order will see the VA hire 1,600 additional counselors within a year, and also assembles a task force that will evaluate mental health and substance abuse treatment, and make a series of recommendations to improve both. “As part of our ongoing effort to improve all facets of military mental health, this order [will]...take steps to meet the current and future demand for mental health and substance abuse treatment services,” Obama’s order reads. “For veterans, service members, and their families.”

For Sean Knapp and his family, however, those efforts aren’t kicking in fast enough. After two years of sobriety, Knapp was recently told that his access to a VA counselor would soon be revoked because of a lack of agency resources. Meanwhile, pending battles over budget cuts in Congress and between the presidential candidates do not bode well for the future of VA health services.

“They told us, ‘You can’t stay in counseling forever,'” Knapp, whose wife Sharlene recently published a book, Blind Devotion, in an effort to help other struggling veterans, says. “But one of the biggest reasons I’m doing well is because I see a counselor in the first place."

Now, Knapp will likely rely on weekly AA meetings and appointments with a civilian therapist to sustain a sober lifestyle, though he says he’d rather meet with someone who, like his VA counselor, has a military affiliation.

“The VA is trying to save money, and I understand that, I guess,” Sharlene says. “But they sent someone somewhere, and now that person is broken. It doesn’t seem to matter to them that all of us, the entire family, is still in recovery. They’re done with us, but we’re not done getting better.”

More the Fix

-

Shaq attacks campus binge drinking

The NBA legend, who lost his uncle to a drunk driver, joins a campaign to highlight the dangers of college bingesSeptember 18, 2012 -

Flying Tomato Crashes to Earth

Double Olympic gold medalist Shaun White is arrested for wreaking drunken havoc at a Nashville hotelSeptember 18, 2011 -

Are Methadone Moms Unfit to Keep Their Babies?

When an addict gets pregnant, doctors advise her to do methadone, not go cold turkey. But to child welfare officials, the woman is still a junkie—and a danger to her newbornSeptember 17, 2012

Shares