When the phone call came that changed his life forever, a BBC reporter asked Salman Rushdie this: "How does it feel to know that you have just been sentenced to death by the Ayatollah Khomeini." It was Valentine's Day 1989. Rushdie thought for a moment and replied, "It doesn't feel good." Then he closed the shutters and locked the front door.

That wouldn't be enough protection. The fatwa -- a death sentence handed down for writing a novel, "The Satanic Verses," which many Muslims believed stood "against Islam, the Prophet and the Quran" -- would stand for another nine years. For many months, fiery protests filled the streets of Muslim cities, but also in London, where Rushdie lived. His book was burned. His translators were attacked; one was even killed. Priests and politicians and protesters demanded he apologize. But Rushdie was an artist. His book was fiction. There was nothing to apologize for.

Principle came with a cost. The fatwa would erase Rushdie's 40s. It would stall the work of a novelist whose first book, "Midnight's Children," won the Booker Prize. It would cost him at least one marriage, and separate him from his young son far too many times. And as Rushdie writes in his new memoir, "Joseph Anton," he often thought that near-decade in hiding would cost him his sanity.

It often seemed that this was happening to someone else. It couldn't be real that there were armed guards in his house at all times, that his movements were restricted, that airlines wouldn't let him near a flight. It couldn't be him being driven 100 mph off the highway, in armored cars, by guards with double-0-licenses like James Bond, just to be sure the very real assassination squads weren't following. And that distance explains both the title and the approach of the memoir. Joseph Anton -- the first names of the writers Conrad and Chekhov -- would become his alias, and it's from that third-person perspective that Rushdie looks back on a decade spent in a virtual prison, all for writing a book.

Have the times changed? "Joseph Anton" arrives at a time when many cities in the Middle East and in Africa are filled with angry protests over the film "The Innocence of Muslims." Once again, Muslims are in the streets and some religious leaders are reiterating that the penalty for defaming the prophets must be death. And a semi-official Iranian religious foundation has reinstated the fatwa against Rushdie; the writer dismisses it as an attempt to generate headlines.

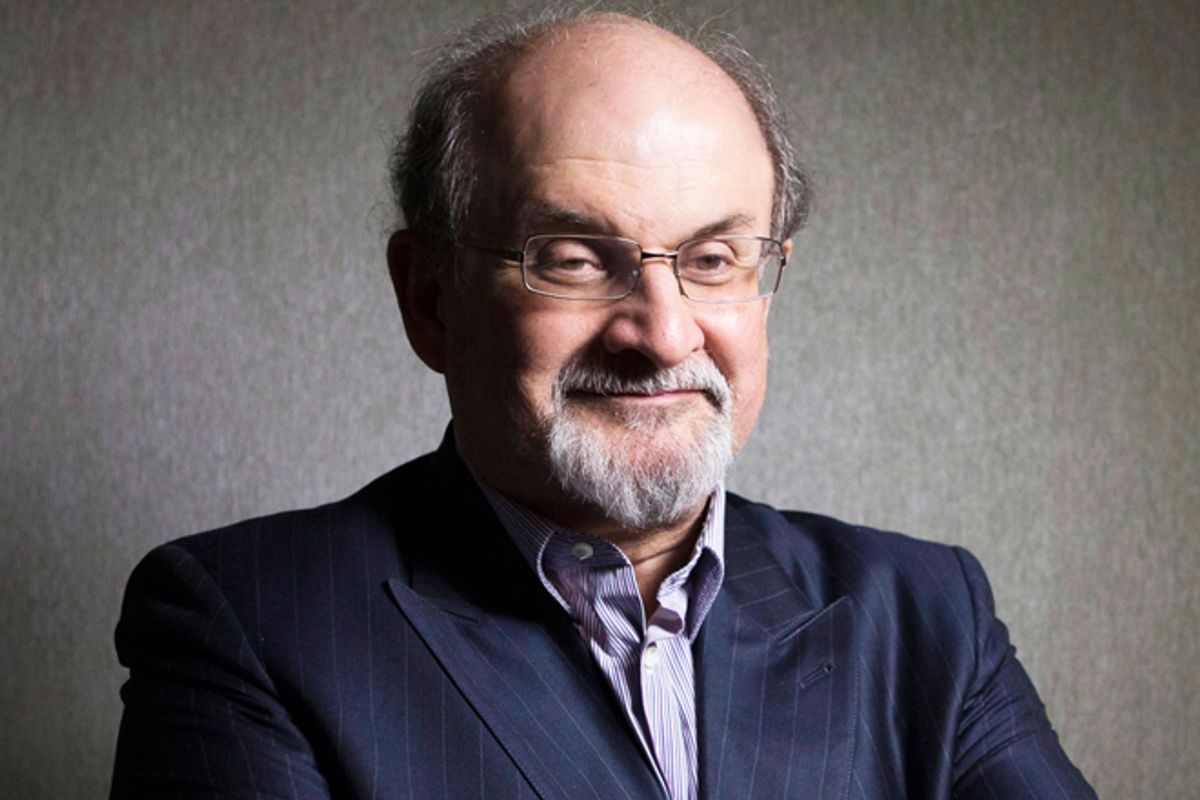

In an interview with Salon on Wednesday, Rushdie talked easily about the personal cost of the fatwa, how he managed to survive nine years in hiding, and about why freedom of speech is always worth defending, no matter the cost.

Were you surprised that there were so many people who were otherwise liberals, probably right-thinking people, in many other ways – in politics, in publishing, in the media, who all fell for this sort of false equivalency and thought that you should simply apologize for causing offense.

Well, yes, I was surprised. Just to balance that, my memory of those times is that the number of people who didn’t fall for it, and who were supportive, was a much larger number. That both in America and England, even in the Muslim world, I had the sense of being very well supported by writers, and even by a lot of journalists. This small minority of people who felt that they needed to shift the blame -- it was surprising, and it’s a thing that I found in many ways more upsetting than the Islamic attack. If bigots behave like bigots, it’s not a huge surprise. If, as you say, people you would expect to get it right don’t, it’s more upsetting.

There were some people on the left who took the cultural relativist stance: You had given offense to a great religion and should apologize. But there was also deeply personal criticism: That you were an opportunist who had intentionally poked a finger in the eye of Muslims, and others who went to the British press and simply called you arrogant and undeserving of being backed in this moment.

Yes, people like John Berger felt that I had just been opportunistic in some way, and done this for fame and money. It reminded me of an interview with Umberto Eco, in which he was accused of something similar – of having written "In the Name of the Rose" for fame and money. And he said yes, if you want to write a book to make yourself famous and a lot of money, you should set it in a monastery where nobody is having any sex -- and have lots of it in Latin. That’s how to write a real best-seller. And I felt the same way. I thought if I was writing a book to be No. 1 in the best-seller list, "The Satanic Verses" might not be that book.

But worse than that was the attempt to paint me as a very unpleasant individual, you know, somebody who is an unlikable character – greedy and arrogant and self-obsessed, an egomaniac, whatever. You name it, I was that. And therefore I was somehow not worthy of public sympathy. That part was very hurtful, and I think in some ways it still is hurtful.

You were "genuinely perplexed" over all the protests and controversy that erupted upon its publication. Did you have any sense that "The Satanic Verses" would cause this kind of uproar? You did have a dream in which you had a feeling the book might come with a "bill to pay."

No. If I had told you on publication day that the following things were going to happen, then you would have been right to call me an egomaniac. The idea that this would happen to a 600-page literary novel did seem to me very implausible. I’m not naive. I understand that the book has a, let’s say, dissident view of the birth of a religion not unlike Islam in it, and that there might be people who didn’t care for that. And I took the trouble to show the manuscript to a number of people who knew a great deal about that world, notably my good friend Edward Said at Columbia. He said, “Well, the mullahs won’t like it.” Both of us thought that with kind of a shrug of the shoulders. OK, that’s not a reason to not write a book, because priests don’t approve. And that was as much as we discussed it. Certainly none of us foresaw anything further than that. I assumed there would be people who wouldn’t like it, but those people hadn’t liked anything else I’d written either. So, oh well, I thought, I’m not writing for those people.

In the book, you write: "When, he wanted to know, did it become irrational to dislike religion, even to dislike it vehemently. When did reason get redescribed as unreason? When were the fairy tales of the superstitious placed above criticism, beyond satire? … It was Islam that had become phobic of a very wide range of ideas, behaviors and things." When, indeed – it's a good question. What do you think the answer is?

Well, I think the attack on "The Satanic Verses" was the first time we had become aware that it had happened. And then it’s been happening more and more ever since. I was 21 in 1968, so I’m as much a child of the '60s as is possible to be. In those years the subject of religion had really almost disappeared; the idea that religion was going to be a major force in the life of our societies, in the West anyway, would have seemed absurd in 1968. We all believed that that conversation was long gone. We were talking about other things. We were talking about civil rights and feminism and the Vietnam War; the subject of religion just never crossed one’s mind. The idea that we would again have to reckon with the militant and aggressive and powerful religious movement or several of them, it just would have seemed like nonsense. I think we all took our attention away from that -- and then it grew back. So I think to that extent it’s our fault we neglected what had happened.

You paid the price, losing nine years of your life to the fatwa, living under the threat of murder and violence. What did it take from you as a writer? How many books do you think you lost as a result, and is that one of the things you look back on with the most bitterness?

I probably lost one, if not two, books in those years. Partly because of the overwhelming force of the event and how much it knocked me off balance for a time, and partly because later on when I sort of regained my balance, just the sheer day-to-day business of trying to run an international political campaign, trying to arrange meetings with governments in different countries with very limited resources, with the help of a small human rights organization and a few friends, was just astonishingly time consuming. There were certainly a couple of years in there where the idea of writing a novel had to be put on the back burner.

But I didn’t do so badly. I wrote “Haroun and the Sea of Stories,” “The Moor’s Last Sigh,” “East, West.” I published a book of essays. I wrote “The Ground Beneath Her Feet,” and toward the end of all this I wrote “Fury.”

Which came out right around Sept. 11.

Yes, I am a little tired of these coincidences. I want them to stop, please.

But the thing that I feel most saddened by is the fact that I lost my 40s, essentially. I was 41 when this started, and the 40s are supposed to be the prime of a man’s life. Instead my 40s were all this crap. I know friends of mine who were around me and helped me through this said to me, years later, in my mid-50s, that “you look younger now.” If I look back at the pictures, I can see exactly what they mean. One of the reasons I didn’t want to have photographs in the book was because I didn’t like the way I looked most of that time.

How did you handle the pressure? You also had a marriage disintegrate during this time, you had a son to raise, and later had a second child. You write about drinking more, and the struggle to control that. Therapy must have been out of the question.

That's the American way. I’ve never had very high regard for therapists. I owe my health, my mental survival, to my friends and loved ones. Bill Buford said "your friends will form an iron ring around you, and you will be able to live inside," and that's exactly what they did.

And how did you manage to write throughout this time? It took several years, but you finally realized Hemingway was right when he said you simply have to sit yourself in the chair and get it done.

I hesitate saying this because it sounds vain, but crisis reveals character -- and one of the things that happened was I discovered I was able to resist. Had you asked me on Feb. 14, 1989, if you had said all of these things are going to happen to you, how do you think you will deal with it? I would probably have said, “I don’t think I will deal with it that well.” I would not have bet on myself to come through it in one piece, and to be able to function. That would not have been my forecast.

But I discovered that I was tougher than I thought, really. I also kept telling myself -- I don’t know if this sounds inflated or not -- but I was inspired by the history of literary persecution. I thought, this has happened before; I am not the first person to whom this has happened. Writers have been in terrible situations and have yet managed to produce extraordinary work. I thought of Jean Genet in prison. I thought of Dostoevsky facing a firing squad. I thought of the writers of Samizdat literature, so on and so on. We both know that the history of literature is full of moments in which writers in dreadful situations have produced great stuff. And I thought to myself, "OK, well, if this is your turn, if you find yourself in the latest of that line of people, don’t make excuses." Yes, you are, as the police said, in a “hell of a jam,” but that’s not an excuse for not doing your work. So, you know, get on with it, I told myself.

As this goes on, year after year, with the fatwa renewed every Valentine's Day, you compare your life to the Bill Murray film "Groundhog Day." You said you never would have made it if you'd known at the beginning that you would have to stay in hiding that many years – that you'd have lost your mind. And in order to try and keep any sense of self, you had to separate yourself – Salman – from the person who is the subject of all these stories and protests – this character you call "Rushdie." And meanwhile you're using another name, Joseph Anton, to stay hidden.

It's true that one of the really difficult things to deal with is these kind of issues of identity. It’s not only one Rushdie who is out there, there’s a lot of people inventing Rushdies to serve their own agendas. And not all of them are hostile, because I felt that even some of the people who were defending and supporting me invented a sort of idealized Rushdie, a kind of iconic Statue of Liberty Rushdie, and I didn’t feel like the Statute of Liberty either. I think one of the things I really set out to do in writing this memoir was to try and say that there was an attempt to demonize me on the Muslim side, there was an attempt in some parts of the defense to idealize me, and I wanted to say “I’m not an ideal individual nor am I a demonic individual. I’m a human being in the middle of this with all the messiness of human beings trying to get through this the best that I can.” And I wanted the book to have a feeling of humanity, to dismiss those false identities, and if you like, reclaim Salman from the crowd of Rushdies.

There are moments in the book -- locking the front door as if it would protect you, escaping London in the early days of the fatwa and going through a McDonald's drive-thru, being given a panic button by your security force that doesn't ever work, walking down the street in New York and having someone stop you and say, "wowie" -- that almost would have felt funny if they happened in a novel. Could you ever see the humor in these circumstances?

It was a thing I used to say to my friends in those days, “If this thing wasn’t not funny at all, it would be quite funny.” With those incidents and others, there were moments which even at the time I had sufficient detachment to say, you know, this is actually funny, even if it's also at the exact same time embarrassing, humiliating, frightening, weird, bewildering. It’s all those things too. But as well as all those things, it’s funny. And I think that happened over and over again.

There's a famous line from "Midnight's Children," originally the first line, that "most of what happens in our lives happens in our absence." Your absence from important moments in your son's life, for your friends, from, as you said, your entire 40s, it was enforced.

I do feel that I managed going on being a good father to Zafar first of all, and then later when he was born, to Milan as well. It was really important for me to do that. It was the absolutely priority above everything we’ve been discussing. That was the absolute priority. A lot of my effort in those years was dedicated to my being able to be a father to my firstborn son and then two sons.

I write in my book about my great nervousness about having a second child, because I thought, you know, what am I going to do? What’s he going to do? Is he going to grow up inside this bubble? How does he go to school? How many lies does he have to learn to tell almost from the moment he’s born? What do we do when he wants to invite his friends home to play? Just how does he have an ordinary life in this situation?

And in the end, deciding to have the child and having him, was just an act of extreme optimism. It was an act of saying, “You know what? I will not accept that this thing will go on forever, and that I will be able to bring him up properly, and he will be able to have a good life.” I just decided that. And by great good fortune, that’s what turned out to be the case.

Are you still carrying any bitterness?

I had to adopt an attitude of trying very hard to let things go, to not carry burdens around with me of who said what about me or who did what, because then I would have been carrying some very heavy baggage all the time. And writing it down, keeping a journal, became a way of letting it go. I could sort of fulminate to myself in the pages of something I knew that nobody would ever read in that form exactly.

So I did try very hard not to literally bear the grudges, because I was trying to not be crippled by this event. I set myself the task very consciously of trying to be the writer I’d always been. Trying to not be too deflected by this event, into cowardice or into bitterness, and that required a lot of letting go. One of the things I do take some pride in, is that if you had never read an article about my life, if you knew nothing about me, except that my books were being set in front of you to read, and if you were to read those books in sequence, I don’t think you would say to yourself, “Oh my God, something terrible happened to this writer in 1989.”

But "The Satanic Verses" is certainly looked at differently. We talked about the separation between Salman and "Rushdie." Something similar happened to the novel when it went, as Martin Amis said, off the books page and onto the front page. There's the novel on the shelf, and the novel that some people think you wrote, the novel they protested and burned.

That was very, very difficult because it was so often particularly at the heat of the storm, in the beginning, the way in which the book was described, all the time, seemed to me to bear almost no relation to the book that existed -- the way in which it was kind of sloganized and reduced to a series of statements which were then described as insults was profoundly upsetting. Some of it still goes on.

This memoir, I was really happy to see, has had a lot of favorable notices, but it’s receiving a very hostile notice in the Guardian, and one of the things that this critic quotes is this fact that is simply not a fact. He says that the novel describes the prophets’ wives as living in the brothel. And if 24 years after the publication of "The Satanic Verses," he still doesn’t know that that doesn’t happen in the book, that’s really, well it’s either stupid or willfully malicious.

But that’s what I’m saying. That kind of sloganizing of the book was very powerful, there were like 10 or 12 statements that the book was reduced to. And those seemed to me all very disconnected from the words on the page in the actual book. It happened to me afterward, there’s a couple of incidents that I describe in the memoir, of people coming up to me, young Muslim objectors of the novel, saying, "Well, then we finally read your book and we couldn’t see what the fuss was about.” They had been the people making the fuss. Because all they had been shown up until then was this set of statements, you know, decontextualized and interpreted as deliberate insults.

For instance, there’s a scene in the novel, in the early days of after the birth of this religion, that in the novel is not called Islam, in which a group of hostile people in this city, which is not called Mecca, were abusing the faithful, which indeed happened. In the real history of early Islam there was a degree of persecution of new Muslims in Mecca, and so I’m describing a scene rather like that, and so obviously if you are dramatizing a scene in which there’s a hostile mob abusing the believers, the hostile mob has to be allowed to abuse and says some abusive things.

And then those abusive things are taken out of the novel and put on a fact sheet with bullet points as being what I’m saying about Islam. And everybody thinks, “Oh, look, he’s saying all these rude things.” That’s the way that the novel was transformed. One of the things I’m pleased about now is that people are reading it like a book at last. Reading it like a novel, after all these years. After almost a quarter of a century, it’s finally being allowed to be a novel. And then it has the ordinary life of a novel. Some people love it, some people are bored by it, some people like it a bit. All of that, which is all fine. People are finally having a literary response to it. Well, it was a bit of a fight to get to that point.

That fight is still ongoing. Across the Middle East right now, there are riots over a video -- a video that was clearly intended to provoke this kind of response. Your novel and the film are two very different things, but the rage in the streets is similar, and once again, people are being asked to apologize for offending Islam. Will this cycle ever end? How do we get out of it?

There’s no end to the conversation about this. But I would say that there’s two things. One is that we need to have the courage of our convictions. That we need to understand that we are privileged to live in one of the relatively few countries in the world where we get to say what we think. Yes, that means that some of those utterances will be unlikable, even objectionable, even insulting, because not everybody thinks well, not everybody’s a nice person. But if you’re going to have the good fortune of living in this kind of society, then you have to cherish it and defend it, that’s just full stop.

We have to not negotiate that. Because it’s too valuable. There are too few places in the world that let you do this. And most of the citizens of the earth do not have these privileges. Increasingly, India doesn’t allow you these privileges. There’s more and more restrictions on free speech in India. China? If you put India and China together that’s two-sevenths of the human race. Add up most of of Africa; try having free speech in Zimbabwe with Mugabe watching you. In most of the world, people do not have this privilege and desperately want it. And we have it, so we need to defend it. That’s one thing. No compromise, no negotiation. This is what we have and we’re not giving it up.

The other side, I think, is to recognize the extent to which there is now a deliberate attempt in the Muslim world -- for reasons of power, not religion -- to manufacture outrage, in order to put mobs on the street, to create an atmosphere of violence and to show yourself a person of great consequence by doing so. You’ve got in Egypt now a Muslim Brotherhood president trying to bid up against the extremists to try and retain the ability to be the person who decides where the country goes.

So on the one hand, we have to hold our ground, and on the other hand it has to be exposed for what it is, the outrage in the street. That it’s not about religion, it’s about power. We need to expose the ruthlessness and the unscrupulousness of these leaders who are doing this for completely corrupt and venal reasons. Exploiting religion in order to create a political atmosphere that they think will benefit them. It’s an old fight, but it’s a fight we need to have.

When the fatwa was lifted, you said that it had been a privilege to defend that right. Still feel that way, despite everything?

Yes, I do think that. I think it more every day.

When I go on a book tour like this, one of the things that always strikes me is that the front line was not me; the front line was bookstores. These are people without armies, without great wealth or resources, without the ability to create a great security environment around themselves, and yet, nobody caved in. I thought that was extraordinary, what these people did -- not so much for me, but for themselves, for believing in the kind of world they wanted to inhabit. The booksellers, and behind them the publishers and translators, that felt like an incredible privilege to be defended by those people and have them standing up for what they believe in and succeeding. We managed to defend this book.

You write that you and your publisher, fortunately, could afford to defend the book. But there's one throwaway line where you mention that had you gone with Bloomsbury as your publisher, things would have been different -- and Bloomsbury might not have been able to discover an unpublished author by the name of J.K. Rowling. You made Harry Potter possible.

Exactly! (laughs) Well, I hope she's fucking grateful.

Shares