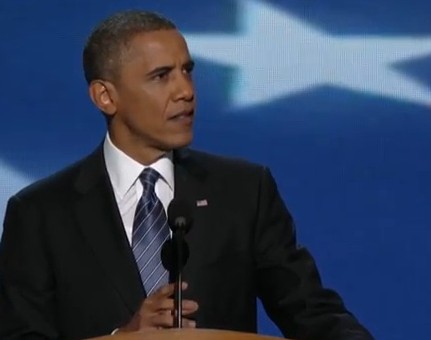

Until not long ago, there was a widespread assumption that the economy could well be Barack Obama’s undoing. After all, no president since Franklin Roosevelt had been re-elected with unemployment as high as it is now, so if Obama were to prevail, it would take an unusual combination of factors that usually matter only on the margins — the skills of the respective candidates, a foreign crisis or two — to allow him to win.

Until not long ago, there was a widespread assumption that the economy could well be Barack Obama’s undoing. After all, no president since Franklin Roosevelt had been re-elected with unemployment as high as it is now, so if Obama were to prevail, it would take an unusual combination of factors that usually matter only on the margins — the skills of the respective candidates, a foreign crisis or two — to allow him to win.

But then something strange happened. The political scientists who think about these things began releasing their forecasts (all of which rely heavily on economic variables), and it turns out that most of them project that Obama will win after all. According to these models, the economy isn’t doing so bad after all. It’s enough to make Republicans tear their hair out.

James Carville may have been right when he put a sign reading “It’s the economy, stupid” on the wall in Clinton campaign headquarters in 1992. But what we mean when we say “the economy” is good or bad, up or down, is less than entirely clear. It also may not mean the same thing as it did ten or twenty years ago. Back then, you would have been forgiven for thinking “the economy” was synonymous with “the stock market,” given how much breathless coverage we saw of every hiccup of the Dow. But since the crash of 2008, few seem to see the market as having anything but the barest relationship to the economy’s overall health. If it did, Barack Obama would be a lock for re-election, given how spectacularly it has performed since he took office. When Obama was inaugurated the Dow stood below 8,000; today it is over 13,000.

But we haven’t heard Obama talking too much about the stock market, even if its rebound has made millions of Americans’ 401Ks a lot healthier than they were four years ago. So which economic indicators do matter?

Each of us can see only a tiny corner of the overall economy — whether we or people we know have lost a job, whether stores near where we live are going out of business. But Americans don’t vote based primarily on their personal situation. This is something political scientists have understood for decades, since they identified the power of “sociotropic voting,” a fancy way of saying that people vote based not on how they’re doing, but how they perceive the whole economy is doing. That means they’re getting much of the information that matters from the media, since if you want to know about the national economy, that’s where you’ll find out. So multiple studies have found that people’s perceptions of the nation’s economy and how they judge the president’s performance on the question are shaped by what appears in the media (see here, for example).

Equally important is that voters’ judgment isn’t about how the economy has done over the incumbent’s entire term — which might seem the most reasonable criterion — but how the economy has been doing lately, or at least as recently as they can recall. As Gabriel Lenz has shown, people’s perceptions of how the president has done on the economy over the course of his term are mostly a function of how they think things are going right now. If I asked you what the state of the economy was in September 2010, you’d probably have a hard time remembering, but you know what you think about today.

That may explain why Gross Domestic Product, the broadest measure of the economy’s health, has a highly imperfect relationship with the outcome of elections. In fact, many of the economic indicators most discussed in the media aren’t particularly good predictors of what will happen in the presidential race. Last year, Nate Silver examined 43 different indicators to see which best predicted the outcome of all the elections since World War II. He found that GDP was only a marginally good predictor of election outcomes, ranking seventh and explaining 33 percent of the variation in the results. The unemployment rate, which is reported constantly and any political commentator could tell you off the top of her head, turns out to have almost no relationship with election outcomes. But the change in employment during the election year was the second-best predictor of the result. In other words, where we are matters less than the direction we’re heading. A good example is Ronald Reagan’s 1984 re-election, which is remembered for his “Morning in America” advertisements showing America as a veritable nirvana where work was plentiful and the population existed in a blissful soft-focus glow. The unemployment rate that November was a high 7.2 percent, only slightly lower than it is now. But what mattered to people was that it had declined from 10.8 percent two years before.

But no matter which economic indicator you’re choosing, 2012 may present the most complex economic picture in generations. We lived through a horrific crash, then the economy rebounded, but not as vigorously as we would like. So how do we judge the president? Barack Obama would like people to sign on to a narrative that extends back before he took office, one of destruction (caused by Republicans) and recovery (led by Democrats). So this is the chart he wants people to see. It begins in December 2007, just before the downturn began. Obama gets inaugurated, and after a few more months of agony, the job losses begin to ebb and the picture finally turns positive in March 2010. You might notice that this shows only private sector job growth. Why? Because it makes for a better picture. The public sector has lost over 600,000 jobs since the Great Recession began, and hasn’t recovered.

Republicans believe that this chart tells the wrong story, spreading blame too far into the past. But the best friend Barack Obama has in getting voters to sign on to this economic narrative is George W. Bush. Rather remarkably, even at this late date, Americans still give Bush more of the blame for the economy’s problems than Obama. This no doubt drives Republicans nuts, but it has changed only slowly as Obama’s term has gone on.

Americans also tend to view the economy through partisan lenses (at least when they talk to pollsters). When there’s a Democrat in the White House, Democrats are far more likely to give the economy positive marks than Republicans; the situation is reversed when the president is a Republican. And in the wake of the party conventions, Democrats’ assessments improved dramatically, likely through some combination of hearing lots of rhetoric about how things are improving and the activation of their partisan identity that the convention produces.

Presidents tend to get more credit than they deserve when the economy is doing well and more blame than they deserve when it’s doing poorly. And one of the striking things about the economy in recent years has been how different indicators don’t move together. Even as incomes have stagnated and job growth has been slow, corporate profits and the stock market have been going gangbusters under Obama (if he’s a socialist class warrior, he’s not very good at it). Ironically, this could contribute to a kind of fatalism on the part of voters that works to Obama’s advantage — no matter what happens, many may conclude, the little guy is going to get screwed, and putting a new person in the White House isn’t going to change that. If things are going just OK — not terrible, but not great — they may decide there’s no particular reason to think the opposition will produce a better economy, however you choose to measure it.