At a time when two of Pennsylvania’s largest institutions have been exposed for turning a blind eye to the sexual abuse of children, the state is preparing to execute a victim of child sex abuse for killing his abusers.

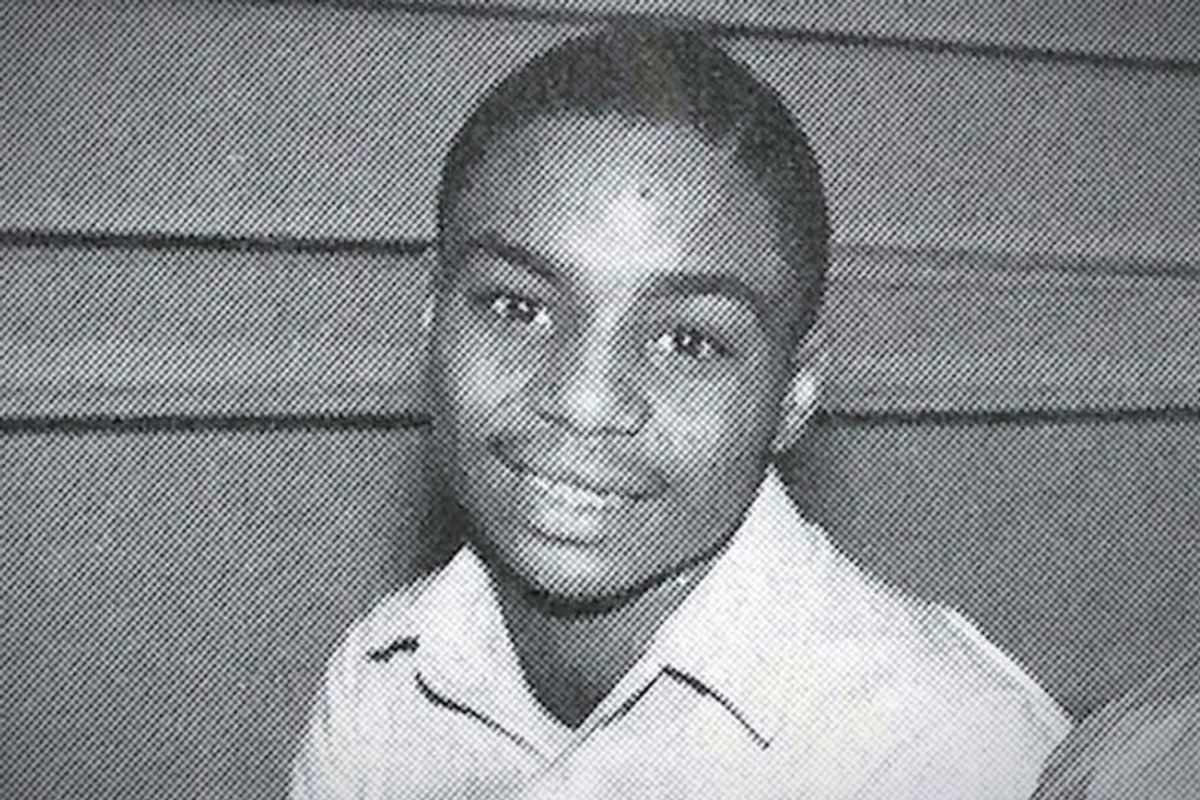

In 1984, less than four months after his 18th birthday — the minimum age required for capital punishment — Terrance “Terry” Williams was sentenced to death for the murder of 56-year-old Amos Norwood, a Philadelphia church leader. With the help of 18-year-old Marc Draper, the son of a police officer, Williams smashed Norwood’s skull with a tire iron, set fire to his body and dumped him in a cemetery. Just five months earlier, Williams was convicted of third-degree murder for killing 50-year-old Herbert Hamilton, who was found naked on his kitchen floor with a knife in his throat.

But according to Williams’ lawyers, both the jury and defense were deliberately kept in the dark about the true motive behind the killings -- the sexual abuse Williams, now 46, endured at the hands of Hamilton and Norwood. At the time, Williams now says, he was too ashamed to admit the abuse. Now he says he was violently raped by Norwood the night before the murder. Five of the jurors that sentenced Williams to death have testified that they never would have done so had they known about Williams’ history of childhood sexual abuse -- and had they known that his victims were also his abusers.

As Williams’ Oct. 3 execution nears, his attorneys are scrambling to save his life. On Monday, the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons rejected a clemency petition. Though the five-member board voted 3-to-2 in favor of clemency, unanimous approval is required for the governor to consider halting the execution. Williams’s lawyers have since asked the Board of Pardons to reconsider, citing an allegedly inaccurate statement made by assistant district attorney Thomas Dolgenos, though it’s unclear whether board rules allow for reconsideration.

Williams’ life currently rests in the hands of Philadelphia Common Pleas Court judge M. Teresa Sarmina, who has the power to grant an emergency stay of execution. Victor Abreu, one of Williams’ attorneys, tells Salon, “The state knew the real motive for the killing and yet presented evidence that was false.” Sarmina is currently reviewing whether this is indeed the case.

At the time of the trial, the prosecution alleged that the killing was motivated by robbery, using the testimony of Draper, Williams’ co-defendant, as proof. But Draper, also now 46, has recanted his testimony and says that he told homicide detectives and then prosecutor Andrea Foulkes on multiple occasions that Williams was motivated by sexual abuse, not robbery.

In an evidentiary hearing held on Thursday, Sarmina listened to nine hours of testimony from Draper and Foulkes, now a federal prosecutor.

Draper, who was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison without parole for his role in Norwood’s killing, says he was promised a shot at parole in exchange for testifying that robbery was the motive. He also contends that Foulkes promised to write a letter to the parole board on his behalf.

Foulkes called Draper’s claim that she ignored evidence of sexual abuse and instructed him to change his testimony “a complete lie,” though she acknowledges having written a letter for him to the parole board in 1988. The hearing is scheduled to continue on Monday.

Ironically, it is Pennsylvania's Republican Gov. Tom Corbett — under fire by some critics for how long it took to bring charges against former Penn State football assistant coach Jerry Sandusky when Corbett was state attorney general — who signed Williams’ death warrant in early August. Some critics have said that Corbett deliberately understaffed an investigation team, so much so that it took three years to arrest Sandusky, during which more children were likely abused.

As a result, it will be interesting to see whether Corbett chooses to intervene on behalf of Williams, a popular high school quarterback and also a victim of sex abuse whose abusers, like Sandusky, appear to have been repeatedly ignored despite being suspected of wrongdoing.

Marc Bookman, executive director of the Atlantic Center for Capital Representation in Philadelphia, tells Salon that, “If there is any state that has a sense of what sexual abuse does to someone, it’s Pennsylvania.” Bookman says he is “cautiously optimistic” that the state will spare Williams. “I would hope that the governor’s experience in the Sandusky case would make him more sensitive and more understanding of the incredible trauma that Terry Williams underwent.”

Despite declarations of sympathy for child victims of sex abuse by Pennsylvania’s politicians and bureaucrats, the prosecution has elected to blame Williams for failing to raise the issue of sexual abuse at his trial. “Instead,” says deputy district attorney Ronald Eisenberg, “[Williams] chose to present false testimony that he wasn't there.” However, Williams lawyers explain that the reason it took Williams so long to reveal his abused history is because he was frightened and ashamed, as are most child victims of rape.

On another occasion, Eisenberg called Williams' plea for clemency a "massive public relations campaign.” Eisenberg’s remarks echo the prosecution’s belief that Williams’ alleged abuse is unimportant in deciding whether he lives or dies. In a statement following the rejection of clemency, district attorney Seth Williams accused Terry Williams “of manipulative and malevolent behavior,” calling his claims of sexual abuse “a last ditch effort to escape punishment for his crime.”

Shawn Nolan, another one of Williams attorneys, has expressed outrage at the prosecution’s argument, saying in a statement, “It is unconscionable that district attorney Seth Williams, who considers himself an advocate and defender of victims of abuse, has allowed prosecutors to characterize the evidence in this case as a 'gay prostitute rage defense.'”

As a child, Williams was no stranger to abuse by older men in positions of authority. The clemency petition filed by Williams’ attorneys describes his childhood as wrought with “abuse, neglect and deprivation,” which “made him an easy mark for sexual predators.” His mother was cruel and abusive, and his stepfather was a violent alcoholic. The sexual abuse Williams suffered began at the age of six, when he was raped by an older boy in his neighborhood. “He came home in tears, bleeding from his rectum. Terry reported the assault to his mother, who saw the blood on his backside but never even sought medical attention for her son, let alone counseling or mental health treatment,” states the clemency petition. Later, Williams was raped by his middle school teacher, Timothy Johnson, and at 16, he was gang raped by two older men in juvenile detention.

Hamilton and Amos, the men Williams ultimately killed, are described in the petition as “middle-aged sexual predators who preyed on teenage boys.” Hamilton, a prescription drug dealer, abused many teenage boys, one of whom testified in the petition. According to Williams' defense, his attempted abuse of Williams resulted in a knife fight that ended with Hamilton’s death.

In an unprecedented outpouring of support, 36 child advocates and sexual abuse experts, 38 law professors, 48 mental health professionals, 55 religious leaders and 36 former prosecutors and judges are calling on the state of Pennsylvania to spare the life of Terrance Williams. Mamie Norwood, the elderly widow of Amos Norwood, one of the men Williams killed, is also among those calling for clemency, saying, “His execution would go against my Christian faith and my belief system.”

Furthermore, over 350,000 people have signed a petition at Change.org urging clemency. The European Union has even chimed in with an “urgent humanitarian appeal” to Corbett and the Board of Pardons, calling the case “particularly distressing because he has been reported to have been sexually abused by the person whom he murdered, a fact which appears not to have been taken into account during his trial.”

Meanwhile, in a letter sent to Corbett and the Board of Pardons, over two-dozen child advocates and sexual abuse experts argue that Williams’ actions were a direct result of sexual abuse. “Terry's acts of violence have, alas, an explanation of the worst sort: Enveloped by anger and self-hatred, Terry lashed out and killed two of the men who sexually abused him and caused him so much pain,” they say. “Terry was left alone to develop the means to deal with the horrors of his daily life.” The letter continues:

His crimes are an undeniable reflection of this internal suffering and are directly connected to his history of abuse and trauma. The violence of his crimes is a window into the true agony with which he struggled. We are saddened by what could have become of Terry Williams' life had someone, anyone, intervened on his behalf.

The letter also points to the significance of understanding the effects of child sex abuse in the wake of Pennsylvania’s recent sex abuse scandals involving Jerry Sandusky and the Catholic Church, saying, “In our Commonwealth, we have seen very public and analogous examples of this phenomenon as major institutions in Pennsylvania have come under scrutiny regarding the sexual abuse of children.”

Though Pennsylvania has the nation’s fourth highest number of death row inmates, prisoners are rarely executed due to a high reversal rate, making the notion that Williams is among the worst of the worst and is deserving of death absurd in the eyes of his advocates. Only three people have been executed since the state reinstated capital punishment in 1978. Williams would mark the first Pennsylvania execution in 13 years as well as the state’s first non-volunteer execution since 1962.

Shares