In their pursuit of liberty and equality in the marketplace, women’s advocates challenged conventional views of motherhood and the divide between public and private life in America. The women’s movement exposed the male-breadwinner model of the economy as a fiction, and women from all social ranks fought for new economic arrangements and cultural norms. In many respects, they succeeded; in some, they failed. Women gained new freedoms in the marketplace, but feminists did not fully resolve the dilemmas of motherhood or win political support for new initiatives to support it. Nor did they harmonize the interests of different groups of women. A similar story accounts for the successes and failures women met when they challenged, at the same time and with equal commitment, another dimension of American life that many considered not just deleterious but cruel and repugnant: their lack of control over their own bodies.

In the late '60s and '70s, women’s advocates cast the female body as a site of political struggle, the place where the intimate and personal became the legal and public and where the personal became the political. In doing so, they put forward reproductive rights as a bedrock of female citizenship. Abortion and forced sterilization emerged as the key issues. Across the country in the early 1960s, state laws prohibited virtually any form of abortion, turning hundreds of thousands of ordinary women each year into criminals, and dozens of states coerced women into sterilization procedures. In response, feminists from all walks of life demanded an expansive bodily integrity for women, which included access to abortion but also freedom from sexual violence and from forced sterilization and control over their own health and sexual identities. They sought to define what it meant to be a full citizen -- not in an abstract sense, but what it meant to be a woman with a body, with biology and with dignity alongside freedom -- and in that basic sense what women’s citizenship itself meant.

Before any progress could be made, women’s advocates had to bring the personal and private world of reproduction into the public realm. Nothing evidences the secrecy of abortion in the United States better than the hundreds of letters that arrived at Patricia “Pat” Maginnis’ San Francisco apartment each year in the late '60s. Written by women from all walks and all stages of life, they were composed when most abortions were illegal. Virtually all the writers were concerned with one thing: the safest and most discreet way to end a pregnancy. “I’m 42 years old, the sole support and mother of 3 children; thus I’m practically desperate at the thought of pregnancy at this point in life,” one wrote. Another hinted at the horrors that could attend the predicament of an unwanted pregnancy: “Last week I tried to do it myself with some pointed objects but nothing happened. I’m desperate and will do anything.”

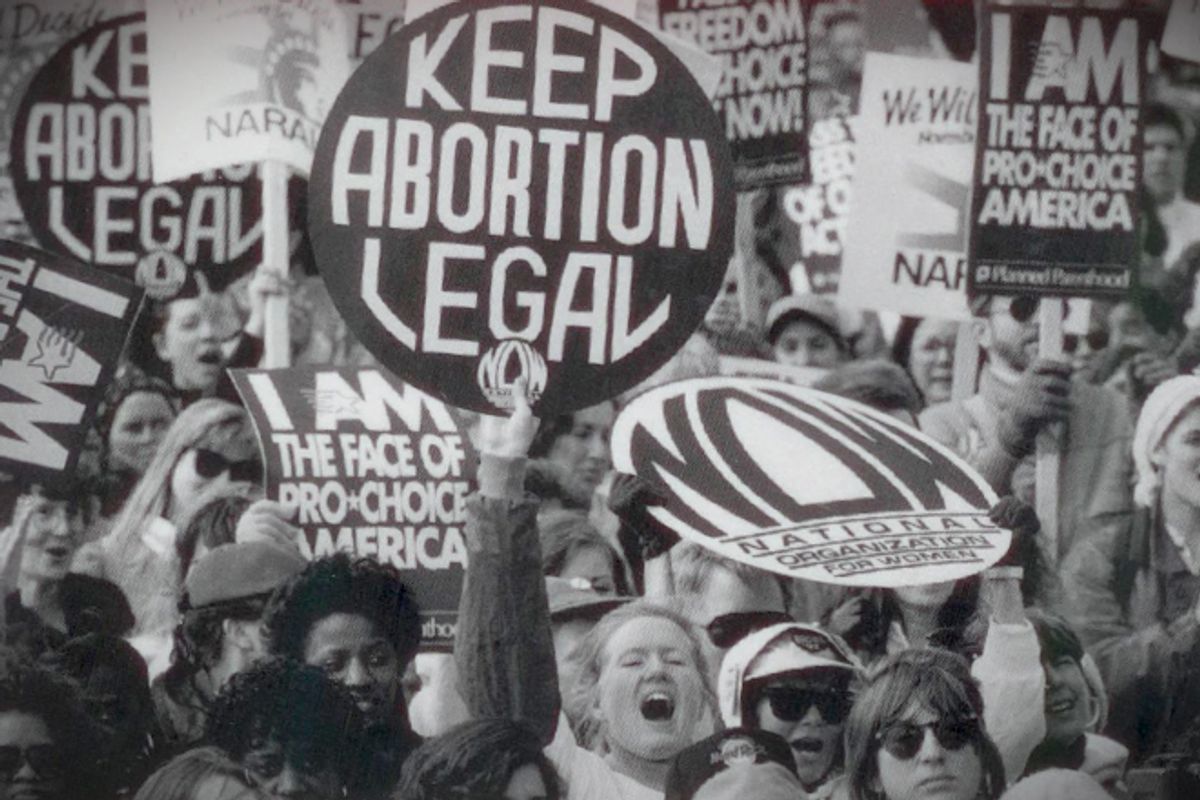

To break open the world of private secrets in which abortion dwelled and make it a public domain of rights required women’s advocates to adopt two parallel strategies. First, they had to wrestle the debate over reproduction away from the male physicians, clergy and population control activists who dominated public discussions of abortion for much of the 1960s. Not until late in the decade did women’s advocates have the numbers and the political leverage to do that successfully. Second, they had to craft cultural and legal arguments that would sway male-dominated legislatures and courts. The National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL) and NOW, the two largest reproductive rights advocacy organizations, eventually settled on “choice,” what they and others called a woman’s right to choose an abortion.

In addition to advocating choice, feminists, like homophiles, had to redefine “privacy.” They had to make abortion public and political in order to protect it as a woman’s private decision. Choice and privacy emerged as critical concepts in the space of seven years, 1967 to 1973, between passage of the first state abortion reform laws and the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade. As a tide of women massed behind demands for “reproductive rights,” liberal activists, justices, and politicians sought to organize such rights under the framework of privacy, a legal domain increasingly recognized by the Supreme Court after 1965. Privacy, it seemed to many, was one of the privileges of being an American citizen and was a liberty shared by men and women alike. However, as a negative right — the right “to be let alone”— access to privacy as a component of citizenship varied sharply by income and race (as well as sexuality). As a result, the possibilities of privacy promised to protect some groups of women while the dilemmas of privacy promised to leave others vulnerable.

Those dilemmas, just like the ones that confronted women in their pursuit of market liberty, derived from class and racial inequalities in American society. In the broadest terms, most reproductive rights advocates embraced individualism for women, a nearly radical concept in the 1960s. Every woman has the right “to determine her own biological destiny,” wrote Bella Abzug, the Manhattan congresswoman and fierce defender of reproductive freedom. Yet that freedom meant little to vast numbers of working-class and poor women for whom abortion procedures were too expensive (or forbidden in public hospitals and under public health insurance) and the indignity of forced sterilization was all too real. For them, in reproductive matters, as in the marketplace, freedom was insufficient without various positive rights to make that freedom meaningful. Thus, for the radical feminists who defended the poor and for feminists of color, “privacy” was too weak a protection for so fundamental a right. They called for “abortion on demand,” the availability of an abortion at no cost for any woman, whenever and wherever she required it, as part of a larger women-controlled health system. Anything less was “compulsory pregnancy” and, as one women’s liberation essay put it, subjugation “by the male medical establishment.”

What all this meant for womanhood, and particularly for motherhood as it was understood in the postwar United States, remains central to the story. Over the first two-thirds of the twentieth century, family planning and the use of birth control grew increasingly acceptable for women; they did not offend “good” motherhood. For millions of Americans, however, that acceptability stopped short of abortion. Family planning remained rooted in the private domain of family and domesticity. But abortion and reproductive rights suggested a more radical liberation of women, an individualism that posited women as prior to, even outside, the family. For many Americans, this was an unacceptable breach of how they understood womanhood. Because abortion undermined their understanding of motherhood and family and constituted the taking of a “life,” for them it could never be the basis for women’s equality. Indeed, they found such an idea as deeply offensive and absurd as other women found strict abortion laws and constraints on women’s reproductive freedom.

* * *

The legal concept that would ultimately be invoked to secure abortion rights for women, privacy, was a compromise; it was the product of an emerging women-centered movement searching for a foothold and an American judiciary grasping for an underlying constitutional rationale to cautiously extend women’s liberties. From 1959 to 1969, abortion activists disagreed among themselves over how to argue for reproductive rights in state legislatures and the courts. The most basic division was between those who advocated reform of existing laws and those who sought repeal of all such laws. Those years deserve close scrutiny because the notion that a right to an abortion might be protected constitutionally by “privacy” had only a handful of advocates before 1969. This decade, characterized by an increasingly urgent debate about what abortion meant — to individual women; to the social order; to physicians and hospitals, under the law; and in the proscriptions of religion — is crucial to understanding how women’s advocates settled on privacy.

Two episodes from that period illustrate the shifting political terrain. In 1962, George McLain, president of the National League of Senior Citizens, testified before an all-male committee of the California Assembly considering reform of the state’s century-old abortion law. “A woman should have the right to determine whether or not she wishes to be a mother,” he told the committee, a notion that dated to the voluntary motherhood movement of the early twentieth century. He scanned the room for Eleanor York, his wife, seated in the audience, who had “done the research on my presentation today.” His dependence on his wife’s intellectual labor, while he sat at the microphone, was telling. The most intimate and personal decisions confronting women about their bodies were debated in the public sphere largely by men.

Seven years later in 1969, Betty Friedan delivered a passionate speech in a packed ballroom at the First National Conference on Abortion Laws in Chicago. There is “no full human dignity and personhood possible for women until we demand the control over our own bodies,” she insisted. Her audience was sympathetic but unprepared for such directness. Those in attendance were accustomed to male doctors and religious leaders, men like McLain, delivering sober appeals to moral conscience and championing cautious reform of existing abortion laws rather than their repeal. Something palpable changed between McLain’s testimony and Friedan’s speech: Women across the country began to seize the microphone, community by community, state by state. Their voices were to carry the abortion debate beyond the cautious reform proposals of the early 1960s and focus it on repeal. Few developments are more emblematic of the extraordinary transformations wrought by '60s feminism than the shift from male to female authority in the abortion debate.

There was widespread agreement in much of the psychiatric, medical and liberal religious communities in the early 1960s that the nation’s abortion laws were broken. Outlawed in every state, safe and legal abortions could be obtained only in the instance of life-threatening danger to the pregnant woman. As a result, each year hundreds of thousands of women — some estimates suggest a million — sought illegal abortions outside the medical establishment. Thousands died or suffered permanent injury. These numbers represented an increase from previous decades, and though there was no single cause behind the climbing figures, an important factor was women’s growing participation in the workplace. As women’s market work increased, and as education became increasingly central to women’s employment chances, so did the cost to them, and their families, of each individual child.

Access to abortion procedures had not always been so limited. In the 1930s, law enforcement officials in major American cities had permitted select hospitals, physicians and clinics to perform extralegal abortions. This imperfect, ad hoc system did not guarantee universal access, but it functioned on the realist premise that abortions were a fact of life. Between the 1930s and the 1950s, however, city and state governments, spurred by the growing public awareness of the ubiquity of abortions and the subsequent moral agitation, all but eliminated this option. Alongside the lavender scare and other war-time and Cold War era efforts to guard domestic normalcy, the mid-century resurgence of a hallowed, and anxious, vision of motherhood drove abortion underground.

Physicians, psychiatrists and public health professionals, mostly male, were among the first to respond to the restrictive legal environment. In 1959, the American Law Institute (ALI) recommended a model abortion law that legalized pregnancy terminations to protect the woman’s health, in the case of rape, and when the fetus was deformed — so-called therapeutic abortions. Deferring to public opinion and with feminism at its nadir, however, the ALI embraced the view that sex outside marriage was immoral, choosing not to frame its law in the language of women’s rights. The ALI model became the basis for the abortion law reform movement, which took shape in the early 1960s and was endorsed by prominent physicians, particularly those associated with Planned Parenthood of America, such as New York’s Alan Guttmacher, who became the organization’s president, and Mary Steichen Calderone, its medical director.

In the early 1960s, a small number of activists began to insist that women’s voices assume a larger place in the abortion debate. Women such as Maginnis, the underground Chicago women’s abortion collective known as Jane, and Rev. Howard Moody’s Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion in New York City asserted the primacy of women’s experience in considerations of abortion. They stressed the harsh reality of illegal “abortion mills” and the dreaded “back alley abortion.” They emphasized women’s anguished search for safe abortions. Others, especially social workers and clergy who worked with poor women, pointed to the class bias of contemporary abortion restrictions. The safer solutions, including expensive trips to legal clinics in Japan, Mexico or Sweden, were viable only for wealthy Americans. Neither argument was doctrinaire, however. Women’s advocates combined aspects of each in eclectic ways as they searched for a language that captured women’s experiences and the social consequences of restrictive abortion laws.

Far too often those consequences were emotional and physical agony. Maginnis and Moody knew the stories by heart. In a typical one, “Susan,” from Tallahassee, Fla., traveled to New York City in the mid-1960s to seek the help of a friend to obtain an abortion. Furtive phone calls led to a midnight visit to a New Jersey doctor. After checking to ensure that “Susan” was pregnant (“Sometimes policewomen try to trap me,” he said), the doctor told them that “I can set up an operating room in twelve minutes in a hotel room.” After a nervous nighttime car ride, a terrifying procedure in a hotel and an $800 dollar payment (more than $4,000 in 2010), the pregnancy was terminated. Unable to access such underground networks or to afford to pay, other women turned to homemade remedies — inserting objects (usually coat hangers or knitting needles) into the vaginal canal, flushing the uterus with soap, chemicals or Coca- Cola, and ingesting a variety of chemical compounds (such as camphor gum, quinine, and turpentine). Illegal abortions were unfortunately common. In New York City, one study of low-income women found that as many as one in ten had attempted a self-induced abortion, and more than one-third knew someone who had. In 1962, 1,600 women were admitted to Harlem Hospital for incomplete abortions. A pastor and abortion counselor in Chicago estimated that “in Cook County hospital, in Chicago, 4,000 women each year are treated for complications resulting from botched abortions.”

The fact that this life-and-death urgency did not yet drive the abortion debate was a source of endless frustration to those who worked directly with women struggling with unwanted pregnancies. Instead, reformers continued to embrace a wide range of rationales for changing abortion law. Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 book "The Population Bomb," which advocated abortion as “a highly effective weapon in the armory of population control,” influenced the founders of an organization called Zero Population Growth, which made “freely available” abortions a central aim of their agitation. Ehrlich’s book sold hundreds of thousands of copies in its first year in print and decisively influenced a 1970 American Friends Service Committee’s (AFSC) study titled "Who Shall Live?" Bemoaning the population pressures exacerbated by the illegality of abortion, "Who Shall Live?" observed, almost as an aside, that abortion laws “invade marital privacy.” The AFSC endorsed abortion law repeal, going beyond mere “reform” of existing laws, but its focus on population control over privacy concerns typified the eclecticism among abortion rights activists in those years.

Privacy entered the rhetoric of repeal advocates through the Supreme Court’s 1965 decision in Griswold v. Connecticut in which the Court held that state laws preventing the distribution of birth control to married couples violated “marital privacy,” a concept that protected, the majority wrote, “the sacred precincts of the marital bedroom.” A breakthrough in birth control politics, Griswold was nonetheless a limited one, bestowing privacy rights only on married heterosexual couples. Harriet Pilpel, a member of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women under President Kennedy and one of the architects of the legal strategy in the Griswold case, envisioned a more far-reaching ruling. She published her vision in Harper’s. “A strong argument can be made that when a woman is denied the right to terminate a pregnancy which threatens her well-being or that of her family,” she reasoned, “[it] jeopardizes her life and liberty in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.” She saw in the concept of marital privacy the promise of individual privacy. And drawing on the work of psychiatrists and psychologists who reported on the personal trauma caused by unwanted pregnancies, she interpreted “well- being” to include psychological and economic health.

But why privacy, as opposed to some other legal framework? The answer requires a brief detour into legal history. As the Court had articulated it in Griswold, privacy was the classic negative right. Subsequent decisions that relied on Griswold consistently grounded privacy in women’s “liberty” to make choices about their lives. In doing so, justices typically cited the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and Ninth Amendment rights “retained” by the people. But just as there had been when “liberty” assumed a central place in women’s access to the job market, there were substantial drawbacks in a similar approach to reproductive rights. Judges could have also invoked, but manifestly and repeatedly refused to do so, the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, which requires a law to treat all citizens equally. An equal protection argument for reproductive rights, as it was later articulated in early-1970s feminist legal circles, had two dimensions. First, it asserted women’s right to control their bodies as a foundation of their basic sexual and economic equality with men. Second, it demanded that all women, regardless of economic circumstances, benefit from abortion reform or repeal. Negative liberty, the equal protection argument went, could not guarantee equality. Only positive rights could.

An equal protection argument was not constitutionally available to women until 1976, however. The Warren Court had not identified women as a suspect or protected class under the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment, as it had African Americans and other nonwhite citizens. Not until a series of cases bookended by Reed v. Reed (1971) and Craig v. Boren (1976) did equal protection become available to women. By then, however, the judicial logic of privacy outlined in Griswold had become the de facto basis for pursuing abortion rights in the courts; few other rationales were ever recognized by judges. Equal protection in reproductive rights cases was also limited by the San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez decision in 1973 (the same year as Roe v. Wade), in which the new Burger Court ruled that the range of protected classes of citizens did not include the poor. That decision marked a conservative turn in equality law with broad implications for the future of reproductive rights in the United States, virtually ensuring that access to abortion would continue to vary with economic class. With equality law effectively dismissed by the legal establishment, abortion rights advocates leaned heavily on the liberty argument available under due process.

Pilpel had not been alone in seeing privacy as an avenue for judicial invalidation of abortion laws. The journalist-activist Lawrence “Larry” Lader, author of the groundbreaking 1966 book "Abortion"; attorneys in the ACLU (after 1972 the ACLU Women’s Rights Project); and a third-year law student at New York University, Roy Lucas, who was to write a key law review article on privacy in 1968, all had begun elaborating the concept of privacy in 1965 and 1966. Without a decisive Supreme Court ruling on behalf of women as a protected class, legal minds in the late 1960s believed that when it came to intimate life and the family, privacy was the soundest basis on which to overturn abortion laws.

As abortion activists plotted their legal challenges, contending legislative approaches emerged. One sought the reform of existing state law based on the ALI model (abortion to protect women’s health), while the other focused on the repeal of abortion statutes altogether (complete legalization). The two approaches had advanced furthest in California, New York, Illinois, Hawaii and Michigan, although activists in a handful of other states, especially Colorado, Iowa and New Jersey, were not far behind. Legal reform efforts were typically advanced by professionals, mostly male doctors and clergy, and middle-class women, usually employed in health care. Repeal efforts, by contrast, were led by a more eclectic group of college-age volunteers, radicalized women volunteering their time, social workers who worked closely with those seeking abortions and, increasingly, feminist attorneys. Reform advocates focused on the physical and emotional harm to women and children, the threat of population growth and the problem of underground markets in abortions. Repeal activists shared some of these concerns, especially the physical and emotional trauma to women, but they spoke in an incipient language of women’s rights that grew increasingly self-assured over the second half of the 1960s.

The experience of abortion activists in California sheds light on the tension between reform and repeal movements as well as on the growing opposition to any change in abortion law. The failure of ALI-style reform bills in the state assembly between 1963 and 1965 led a sympathetic group of physicians, clergy and professionals to form the California Committee for Therapeutic Abortion (CCTA). Its speakers suffused the state, addressing more than 300 meetings in a ten-month period in 1966. They lobbied legislators, published a newsletter and drew more than two dozen statewide organizations into a big-tent coalition. Just over a year later, in June 1967, the assembly passed the Beilenson bill, based on the ALI model, which Governor Ronald Reagan signed. Beilenson, like most such state laws, created state boards to oversee abortion decisions and monitor the number performed by individual hospitals. Though less restrictive than previous abortion laws, it nonetheless fell far short of broad access.

As the CCTA was leading the drive for reform, Pat Maginnis launched a repeal campaign. She founded the Society for Humane Abortion Laws in 1965 and, along with a small group of like-minded activists, traveled across the state teaching women how to perform abortions on themselves and doing radio interviews, all while running an abortion referral service out of her home. She personally referred thousands of women to physicians and clinics in half a dozen countries, as well as to underground abortion clinics in the United States. She fervently believed that reform was a dead end, and her frequent arrests testified to her unwavering commitment. Reform still left far too many women treated as criminals for actions she believed to be a right. “The most gross invasion of privacy,” Maginnis said after she had been arrested for distributing literature on abortion, “is the use of police surveillance to control what should be a private matter between a woman and her physician.”

Reform and repeal advocates disagreed over how much freedom women should have in reproductive matters, but their opponents fought all proposed changes to abortion law with equal passion. In California, as across the nation in the 1960s, the principal opponent of both reform and repeal was the Catholic Church. The U.S. church had emerged from the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) divided into a liberalizing laity and a hidebound leadership. A 1966 statewide poll in California revealed that half of all Catholics disagreed with the church’s teachings on abortion while, at the same time, leading bishops were calling for a “murder in the womb” campaign against any changes to the law. Labeling the cautious ALI-style bill an “infant slaughter law,” California’s Catholic leadership spoke of the “slaughter of innocents” and fought liberalization at every turn. Catholic antiabortion activists published photos of unborn fetuses, labeled abortion “infanticide” and likened it to the eugenic practices of fascist Germany. After the passage of the Beilenson bill, California’s experience became the national experience and set the tone of the abortion debate for decades to come. While reformers and repeal advocates saw abortion in terms of public health and rights, opponents framed the issue in terms of human life, the “sacred” life of the fetus. They spoke past, rather than to, one another.

As additional states held hearings and considered reform legislation similar to California’s between 1967 and 1969, it became increasingly clear to repeal advocates that a woman’s right to control her own body was not driving the conversation. Three moments of public activism in 1969, however, reoriented abortion politics around women’s voices and bodies. In February, the Redstockings -- one of the first women’s liberation collectives, which was founded in New York City by Kathie Sarachild, Shulamith Firestone and other young radical feminists -- attended hearings on a proposed abortion reform law in Albany, N.Y. Fourteen men and one woman were scheduled to address the committee, and the lone woman was a Catholic nun. After sitting quietly through several speakers, Sarachild leaped to her feet and bellowed, “Now let’s hear from the real experts!” Others joined her, shouting, “Repeal the abortion law, instead of wasting time talking about these stupid reforms!” For the first time a state legislature was forced to engage directly with the women’s liberation movement. No longer content to see women sitting in the back of the room while men cautiously debated issues central to women’s experience, the Redstockings, along with NOW members picketing outside, declared women the “only experts” on abortion the assembly needed to consult.

The second moment took place the same week when more than a dozen organizations and 350 individuals met in Chicago to convene the First National Conference on Abortion Laws: "Modification or Repeal?" It was in front of this audience that Friedan demanded “control over our own bodies.” In the same speech, she echoed the Redstockings’ Albany refrain: “I am no expert on abortion, but I am the only expert there needs to be now ...” Organized by the physician and feminist Lonny Myers, a tireless advocate for the legalization of abortion, the Chicago convention led to the creation of the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL). Myers and Ed Keemer, an African American physician who had been jailed for performing abortions in the 1950s, assumed the reins of NARAL, which quickly drew into its orbit a national network of feminist activists, such as Maginnis, Carol Greitzer, Shirley Chisholm, Lucinda Cisler, Lana Clark Phelan and Lee Gidding (who was to become executive director). Within a few years, NARAL’s board of directors would be dominated by feminists who ensured that women’s reproductive rights remained at the center of the national debate over abortion.

The third development followed quickly on the heels of the other two. In March 1969, at a church in Washington Square on the edge of Greenwich Village in New York City, twelve women “rapped” about their own abortions before an audience in excess of 300 people. The first abortion speakout, as it became known, represented the emerging women’s liberation call to reveal the personal to be political. Sponsored by the Redstockings, the speak out had a straightforward aim: to push the most deeply private matters of being a woman into the public arena and thereby to expose the grip of patriarchy on women’s lives. Reclaiming their bodies, for the radicals at the speakout, meant more than reproductive choice. It meant reclaiming female sexual desire and sexual freedom, which was impossible so long as women bore responsibility for unwanted pregnancies yet could not abort them. “The laws are not made in terms of a woman,” one woman said at the speakout. Moreover, women were imagined as owing their reproductive capacity to society, another observed. Women are thought of as having “a debt. We have no debt.”

Thus was 1969 the turning-point year in the national debate over abortion. The energy of that year — indeed, of just its first three months — was the product of forces unleashed by the emergence of women’s liberation. Between 1969 and 1971, women threw their support behind their local NOW branches, NARAL and scores of local and state-level organizations devoted to abortion law repeal. Others eschewed such traditional advocacy and founded women’s collectives, liberation “cells” and all manner of women-only groups based on the principles of participatory democracy and women’s self-determination. Both inspired by and deeply disgusted with the 1960s New Left, women turned their backs on its cult of masculinity.

In thousands upon thousands of consciousness-raising groups, in women’s centers, in living rooms and in other formal and informal settings, women began to rethink feminism. Now, as never before, sex — the act, its politics, its outcomes, its cruelties, its joys — mattered. For many women, this new feminism was a reaction to what Robin Morgan called “the counterfeit male-dominated Left”: the antiwar and civil rights men who condescended to or dismissed women’s issues while taking women’s labor for granted and assuming their bodies to be sexually available. For Michele Walker, a founding member of the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO), it took “three years to understand that the countless speeches that began ‘the black man ...’ did not include me.” Morgan and Walker were joined by Gloria Steinem, Frances Beal, Kathie Sarachild, Flo Kennedy and perhaps two or three dozen other prominent writers and organizers who emerged as spokeswomen for the diffuse women’s liberation and Third World feminist movements.

Even more than sex, the body moved to the center of women’s politics. Women’s liberationists recognized that what they had been taught to think of as personal and private was in fact social and political — not unlike homophile activists and their eventual successors in the gay liberation and gay rights movements. Bodies might be individual, but their treatment by society, medicine, the media, and other male-dominated institutions constituted a collective political problem for women. This newfound understanding, coupled with an ethic of togetherness, produced a surge of activism and institution-building nearly on par with the black freedom movement. Their energy and their numbers, as much as any other single force, changed the context in which Americans discussed abortion.

“Women’s liberation played an important part in the passage of this bill,” New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller declared when he signed the nation’s most liberal abortion law in April 1970. Albert Blumenthal, a Democrat from Manhattan, and Constance Cook, a Republican from Ithaca, led the legislative fight for abortion reform in New York State, but as Rockefeller and other leaders of the liberal wing of the Republican Party recognized, absent the lobbying, demonstrations and publicity generated by the women’s movement -- and especially abortion rights activists and organizations from New York City, Syracuse, Buffalo and Ithaca -- their efforts would have met with defeat.

The notion of reproductive rights enjoyed a spectacular ascent in the nation’s consciousness in the last years of the 1960s. In 1965, abortion had been a taboo subject, rarely discussed in public. Five years later, millions of women viewed restrictive abortion laws as an obstacle to their full citizenship to the same degree as workplace discrimination. During this period of activism and reform, four states — New York, Hawaii, Washington and Alaska — eliminated nearly all restrictions on abortion within the first trimester. Other states, notably California, Colorado, New Mexico, Georgia and Oregon, passed ALI-style reform laws, and 10 other states passed some kind of reform bill. Though these results fell far short of what most activists believed necessary, in historical perspective the transformation in both law and public opinion had been swift.

The successes of abortion activists at the state level were a direct result of their ability to build powerful coalitions composed of women’s groups, liberal clergy and medical professionals. These groups united around the notion of choice. Calling abortion a woman’s private choice, however, is not the same thing as grounding the right to make that choice on the legal concept of privacy. NARAL and other women’s advocates asserted the “inalienable right” of every woman, as Shirley Chisholm said at NARAL’s inaugural press conference, “to choose whether or not she will bear children.” However, the constitutional doctrine of privacy did not then, and does not today, secure anything close to the inalienability Chisholm desired. Because it is a negative right — “to be let alone” — privacy does not ensure that any woman who needs or desires an abortion will be able to have one. Attorneys forged ahead with the privacy argument regardless, because it remained the most powerful legal tool at their disposal. In September 1969, the California Supreme Court ruled in People v. Belous that the language of the state’s pre-reform abortion law was unconstitutionally vague and that “a ‘right of privacy’ or ‘liberty’” included a woman’s “fundamental right to choose whether to bear children.” Two years later in United States v. Vuitch, the U.S. District Court for Washington, D.C., cited “a woman’s liberty and right of privacy” as the linchpin of reproductive rights.

“Privacy” was thus a compromise between women’s emerging struggle for self-determination and a jurisprudence set in motion by Griswold. The concept had multiple advantages. Among religious Americans, it suggested an individual conscience wrestling with a complex and difficult moral decision. Motherhood as the responsible choice of an individual woman resonated with broader, liberalizing shifts in American attitudes toward consensual sex — at least heterosexual sex. Nonetheless, privacy and choice, with their undeniable commonsense appeal, made the fight for abortion rights a fight for individual freedom. And as with the fight for workplace rights, conceiving of access to abortion as a “negative” right to individual liberty meant that social inequalities would as often as not determine the quality of the liberty afforded by privacy. And, like employment law, abortion law was left vulnerable to erosion by its opponents and subsequent Supreme Court decisions.

Excerpted from "All in the Family: The Realignment of American Democracy Since the 1960s" by Robert O. Self, published by Hill and Wang, a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright © 2012 by Robert O. Self. All rights reserved.

Shares