“You are going to suffer,” an old monk said to me upon my arrival at Wat Tham Krabok, a Buddhist monastery a couple of hours north of Bangkok, after I’d introduced myself as an opium addict.

Buddhist monasteries have traditionally acted as places of refuge. Wat Tham Krabok is no exception, but this particular wat (Thai for “Buddhist monastery”) goes above and beyond tradition. Here, under the auspices of monks, novices, and nuns in toga-like robes, you will find scores of recovering drug addicts from countries all over the globe, ready to take a particularly unpalatable cure involving five days of induced high-intensity vomiting.

The detox facility at Wat Tham Krabok had been founded specifically to treat opium addiction, but that was fifty years earlier, back when the vice was commonplace. Now, except for that one elderly monk, no one at the wat remembered ever having treated an opium habitué. He backed off from his initial pronouncement when he found that I had been heavily into it for only a few months. “We used to get addicts who had been smoking opium daily for ten or twenty years,” the old monk explained. “The local people used to complain that at night they could hear the addicts’ screams all the way into town.”

These were my unusual circumstances when I arrived at Wat Tham Krabok in November of 2007: After helping to report a story for the Asian edition of Time magazine in 2001, about how Chinese-style opium dens had somehow survived the 20th century in isolated, landlocked Laos, I had become a self-taught expert on opium paraphernalia. This in turn inspired curiosity as to how the relics were used, and I began experimenting with the drug—vaporizing opium in the traditional manner with a long bamboo pipe held over a glowing oil lamp while reclining on a woven grass mat.

But after seven years of curious dabbling I had awoken from my pleasant dream and found myself a voracious opium fiend with a 30-pipe-a-day habit. My costly and time-consuming vice had left my editors bewildered and my bank account empty. I needed a way to get clean with as little attention and expense as possible, and the monastery on the edge of the jungle seemed the only way out.

There were about fifty drug addicts in treatment at Wat Tham Krabok when I arrived, a handful of them foreigners like myself. The vast majority were Thai men who were there for methamphetamine; the Westerners were a mixed bag, both in gender and the habits which they were trying to kick. Among the Westerners, I was a standout not only for my anachronistic addiction, but for the fact that I was fluent in the local vernacular. Thus, despite having just arrived at the wat, I soon found myself acting as a liaison between the Thai monks and the Western addicts, many of whom had recently arrived in Thailand specifically to take the cure and were very much out of their element. My circumstances gave me some unique insight into the workings of the monastery and its unusual detox technique.

The daily routine began before long dawn, when the ringing of an old schoolyard bell shattered the morning calm and almost invariably startled me out of some fevered dream. A bed and surroundings to which I have yet to become accustomed usually guarantee that I’ll be visited by nightmares, and coming off opium seemed to push my nocturnal musings to disturbing levels of intensity. Yet awakening to find myself at the wat didn’t exactly bring immediate feelings of reassurance. Here I was starting my first day of treatment, wearing a strange uniform in a strange place, and surrounded by strangers.

The first order of the day was sweeping. Crude bamboo brooms were handed out and dead leaves that had dropped from the wat’s many mango trees were swept into small piles. The task was carried out in the dark, and there was minimal talking among the fifty or so addicts taking part. This daily chore was of the sort that could be termed “mindless,” but it also afforded some time for self-reflection. We swept leaves for about half an hour, and then made offerings of burning incense sticks to a shrine containing the mortal remains of the monastery’s founding abbot. Whispering in the darkness, we all regrouped for morning calisthenics.

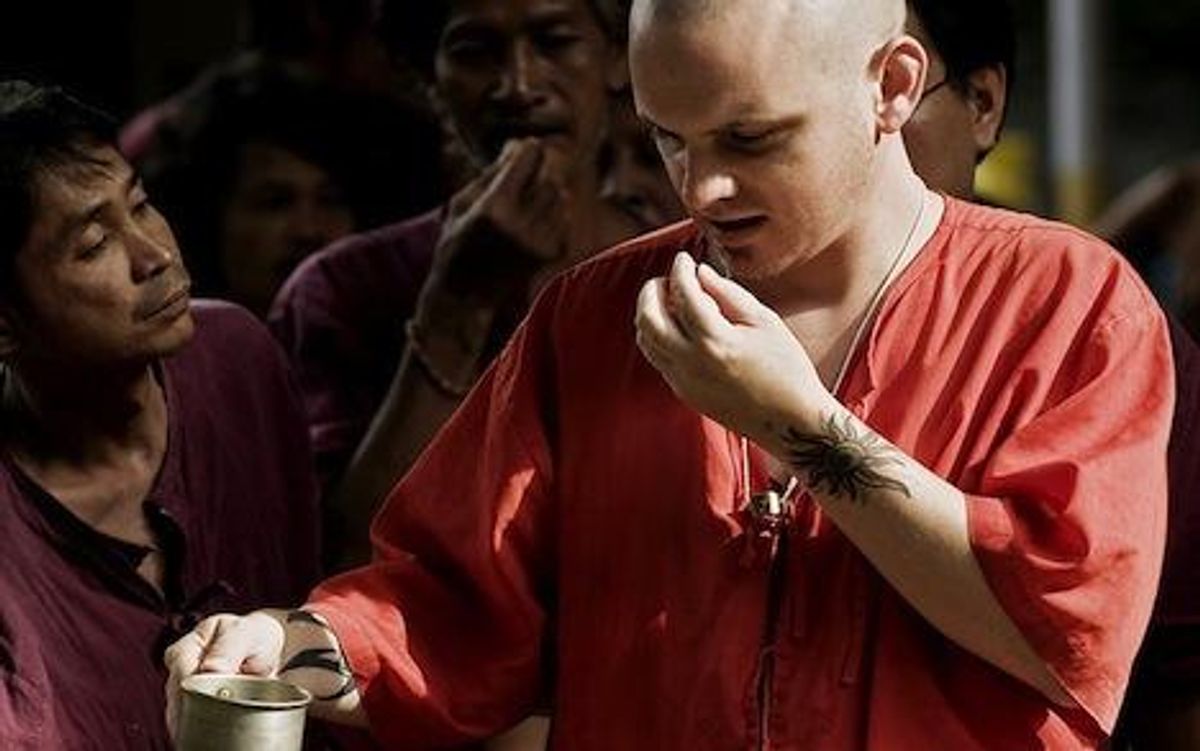

Thai culture is by nature non-confrontational, but I noticed one of the monks carrying a yardstick-length bamboo stick just in case some persuasion was necessary. Still, for a place housing scores of young men coming off meth, the monastery had a surprisingly mellow vibe. The morning routine ended with roll call and a cup of bitter tea that was said to cleanse the blood of toxins. After breakfast, addicts who had already completed their initial five days of detox (which included the all-important vomiting cure) were grouped into working parties and led off to different corners of the monastery. For the newly arrived like myself, the midday hours were free, and this allowed me to get to know some my fellow addicts and the Thai staff.

It was during this time that I met Saundra, a forty-something former heroin user from England who had completed the detox years before and then decided to take the vows of a Buddhist nun and extend her stay at the monastery indefinitely—something all successful participants in the program have the option to do. With a shaved head and eyebrows, and wrapped in a white robe, Saundra described to me how the vomiting cure was supposed to work.

I was to take this most important part of the treatment over five consecutive days. A secret elixir, the ingredients of which were said to have come to its discoverer in a dream, had to be downed from a shotglass in a single gulp. The potion was a purge and not to be digested. The articles I had previously read about Wat Tham Krabok were illustrated with photos of spectacular bouts of projectile puking—but this was not typical. Saundra told me that I might have to stick a finger down my throat to get the vomiting started. I would be joined by a number of other addicts who were also on their first five days of the cure.

The treatment was the main event of the day and very much public. In fact, busloads of schoolchildren were sometimes in attendance—in hopes that the nauseating spectacle would be a deterrent to future drug use. “The trick is to stay relaxed and focused,” Saundra advised. “Block out the noise around you. As long as you stay focused you’ll not have any problems.”

I might have backed out of the program had I known beforehand exactly what I was getting myself into. The purge was done outdoors on a wide concrete patio, where I kneeled with a handful of other addicts over a shallow cement trough. There was no doubt about what function the reeking pit was going to serve.

Without ceremony, a monk poured the muddy potion from a bottle into a shot glass, and then handed it to me. I did not stop to think about what was about to happen or sniff at the glass, but instead knocked back the dose like it was a shot of tequila. The taste was absolutely vile, and I shuddered. But despite the withering vapors venting through my nostrils and the burning lump sliding into my gut, I did not immediately vomit. A monk instructed me to drink as much water as I could hold, and I gulped down cup after cup until I was woozy. Still there was no urge to vomit. As Saundra had advised, I then jammed two fingers down my throat and, as though priming a pump, this act brought forth torrents of rust-colored puke.

I vomited until the deluge became dry heaves. Exhausted, I wiped the strings of saliva and snot from my mouth and nose and tried to catch my breath. Saundra shouted at me over the noise of the crowd: “You’re not finished! You have to get all the medicine out of your body. Drink more water! Just like before, drink until you are going to burst!”

Addicts on either side of me were doing the same, all while a crowd of spectators sang songs to conga-drum rhythms and cavorted about while we gagged and retched. All of it was meant to be encouragement, of course—moral support from the addicts who had already completed their five days of vomiting. In the end Saundra was right: Staying focused on the goal of breaking my addiction got me though a week that was as demanding as it was miraculous.

Except for food and drink, treatment at Wat Tham Krabok is free, and, like all Buddhist monasteries, it relies on donations. Anyone contemplating a visit should remember that the place is not a day spa. Show up expecting to be waited on hand and foot, and you will not last long. Living conditions at the wat are very typical of Buddhist monastic life, which is to say they are decidedly rustic.

Statistics on how many are able to stay clean and how many have relapses vary widely, but at Wat Tham Krabok one thing is certain: You can only do the cure one time. Once you check out of the monastery’s drug detox program, you will not be allowed to check back in, no matter how unique your excuse for having had that setback.

On my last day at the wat, I met with the abbot. He placed in my hand a ring with the monastery’s name engraved around a blue stone, and a slip of paper with a short Buddhist mantra written on it. Both were to remind me of my time at Wat Tham Krabok, and to help me fight temptation. The abbot made it clear that the week I had just completed was the easy part—that the real test lay ahead. In my jubilant state, newly free of my 19th-century addiction, I failed to take his warning seriously.

Freelance writer Steven Martin was born and raised in San Diego, and has spent the past three decades traveling and living in Southeast Asia. Steven’s memoir, Opium Fiend: A 21st Century Slave to a 19th Century Addiction, was published in July by Villard, an imprint of Random House.

Shares