Studies have shown that memory and recall are more fallible than failsafe. That finding undermines eyewitness identifications—a critical prosecution mainstay—revealing them as far more fragile evidence than imagined. Just ask Rickey Dale Wyatt of Dallas, Texas. On January 4, 2012, he was released from prison after serving 31 years of a 99-year sentence for a rape he did not commit.

Studies have shown that memory and recall are more fallible than failsafe. That finding undermines eyewitness identifications—a critical prosecution mainstay—revealing them as far more fragile evidence than imagined. Just ask Rickey Dale Wyatt of Dallas, Texas. On January 4, 2012, he was released from prison after serving 31 years of a 99-year sentence for a rape he did not commit.

Police were sure that a single rapist had committed a cluster of rapes when they arrested Wyatt for three assaults.

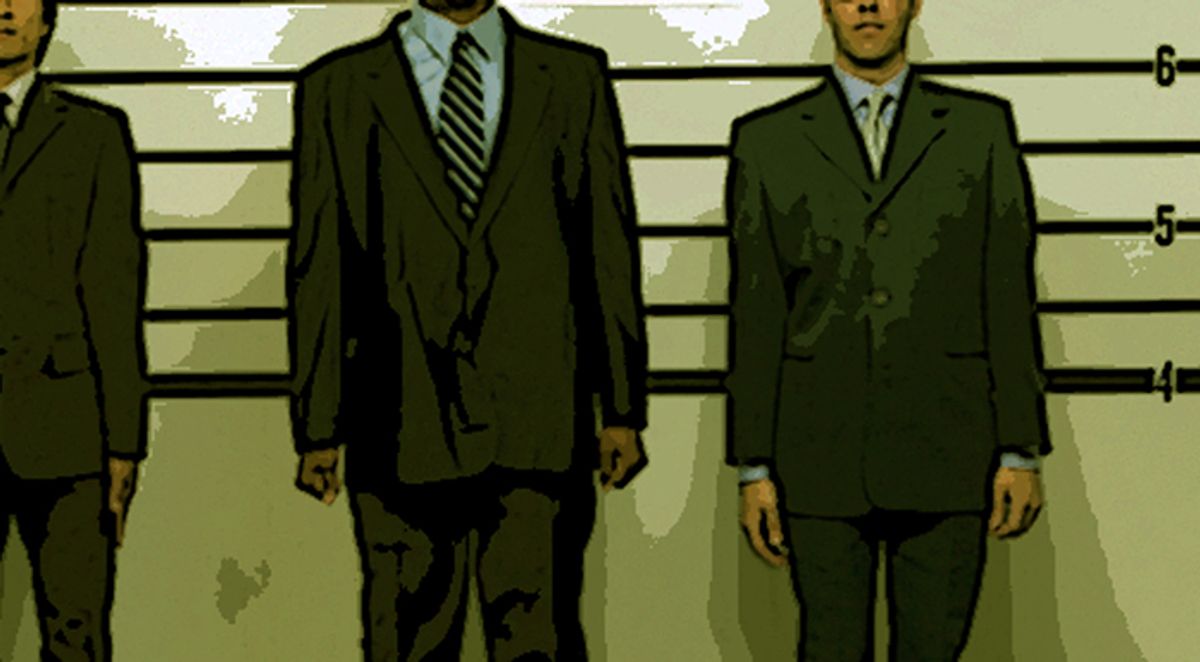

The third victim, who had been grabbed from behind and dragged at knifepoint to a dimly lit area, was the first to identify Wyatt. Ultimately, all three picked Wyatt from photographic lineups. All had described their rapists as being between 170 and 200 pounds, between 5’9” and 6’, and as having no facial hair. Wyatt is 5’6”, was close to 140 pounds—and he had abundant facial hair and a mustache.

While Victim No. 3 identified Wyatt in the photo lineup, she had failed to do so in a live lineup (which wasn’t recorded). That failure, and knowledge of the lineup’s very existence, was withheld from Wyatt’s defense attorney.

Wyatt stood trial for one rape: the first. While his nephew testified that he’d never weighed more than 140 pounds, a police officer testified that after Wyatt’s arrest the suspect had lost approximately 30 pounds in 10 days.

Wyatt, then 25, declined a plea deal for a 5-year sentence and defended his innocence in front of a jury. He lost.

There was much that jurors did not know. Innocence Project lawyers who eventually fought to free Wyatt found that police and prosecutors held back exculpatory photographic evidence of the physical appearance mismatch—then-recent photographs showing Wyatt with facial hair, weight approximately 135 pounds. They also alleged that a report in which the third victim put her attacker at around 200 pounds was suppressed; at his sentencing hearing, the third rape victim publicly identified Wyatt as her rapist.

Wyatt’s complex case had more problems than just lineup problems, starting with an inadequate legal defense. Body fluid tests did not link Wyatt to the rape, and his trial lawyer failed to challenge it. The attorney also failed to present evidence like recent hospital records that would have shown Wyatt had facial hair.

Wyatt’s conviction was vacated thanks to the efforts of the Innocence Project and Dallas’s Conviction Integrity Unit and District Attorney’s office, which pushed for DNA testing. Also key: the city of Dallas’ propensity for saving physical evidence likely to have been discarded elsewhere to save on the cost of storage.

The need to reform eyewitness identification procedures has been recognized in recent years, but actual changes have lagged. Although the Department of Justice issued its “Eyewitness Evidence, A Guide for Law Enforcement” (pdf ) in 1999, calling for written protocols on eyewitness evidence, many U.S. police departments still lack written protocols. Last June, 10 states including Texas enacted legislation requiring all law enforcement agencies to create written procedures.

Misidentification is the single biggest common denominator in wrongful convictions, and a factor in 72 percent of cases overturned by DNA nationwide. In 50 percent of those convictions, shaky eyewitness testimony was not shored up by physical evidence or other corroboration like a confession or informant testimony.

In 2001, New Jersey became the first U.S. state to adopt federally recommended guidelines on witness identifications after mounting awareness of the old methods’ fallibility (such as eyewitnesses being influenced by unintentional verbal or body clues from investigators).

But those improvements still didn’t go far enough, said experts.

The 2004 case of Larry Henderson, sentenced to 11 years for reckless manslaughter and weapons possession in connection with a fatal shooting in Camden, pushed New Jersey to examine its standards again.

In his appeal, Henderson argued that police had failed to follow the guidelines adopted in 2001 and that the police photo lineup conducted 13 days after the murder improperly swayed a witness to pick him out. The witness later testified that a police officer had moved the photographs around as if hinting which to select and that “there was pressure” to make a choice.

An appellate panel in 2008 called the Henderson lineup “a charade” and ordered a new hearing on the photographic evidence’s admissibility. The state appealed. In response, the New Jersey Supreme Court said that before it would address the issue, it wanted a full inquiry into procedures used in the state’s eyewitness identifications.

That’s when, says Barry Scheck, cofounder and co-director of the Innocence Project at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University, “they did something that courts should do much more with science and the law. … They remanded it to a special master, a very smart retired judge”—in this case former New Jersey State Appellate Judge Geoffrey Gaulkin.

Gaulkin’s task was to determine if New Jersey’s identification procedures were scientifically sound. He held hearings and reviewed more than 2,000 pertinent scientific studies published since the 1977 introduction of the Manson test. The test is a two-step process that first decides whether the eyewitness procedures police used to identify a suspect were impermissibly suggestive. If so, courts must then determine, using a five-part reliability factor test, whether the identification still should be admissible. Bottom line: even if there are problems with the procedure, unless there is a “very substantial” likelihood of an “irreparable” misidentification, courts must allow the identification into evidence.

In a June 2010 report (pdf), Gaulkin wrote that the short answer to the court’s question whether the test and associated procedures were “‘valid and appropriate in light of recent scientific and other evidence’ is that they are not.”

His report called for a major overhaul of the legal standards governing whether or not eyewitness testimony is allowed in court. And he recommended that memories be treated as “fragile, difficult to verify and subject to contamination.” During his research, he’d come to view them as more akin to trace evidence: “a fragment collected at the scene of a crime like a fingerprint or a blood smear, whose integrity and reliability needs to be monitored and assessed from the point of its recovery to its ultimate presentation at trial.”

Not only can law enforcement unconsciously lead a witness towards identifying a suspect, he noted, but they—along with other witnesses or family members—can unconsciously contaminate a witness’s memory. What those people say and do can bolster, indeed overinflate, a witness’s level of certainty in their identification.

Cognitive neuroscientist Itiel Dror of the University College of London points to psychological research that shows “time and time again no correlation between confidence and accuracy.” Yet heightened confidence can easily be mistakenly read that way, leading a court to allow improperly overstated evidence and jurors to give it too much weight.

Gaulkin recommended that judges and juries alike be made fully aware of all scientific facts that can impact eyewitness identifications’ trustworthiness and that the burden be on prosecutors to provide proof that evidence and testimony is reliable. He concurred with Innocence Project recommendations that courts examine scientific variables that can impact accuracy by hearing testimony from eyewitnesses and police officers pre-trial at admissibility hearings.

“That was a very big deal,” says Barry Scheck. “For years, we’ve been working with experimental psychologists on eyewitness identification issues and on getting the courts to change their standards for assessing that evidence, and on changing the way they do pretrial reliability hearings to make them more in accordance with the science.”

Professor Daniel Medwed of the S. J. Quinney College of Law at the University of Utah, also favors pre-trial review. “It just enhances decision making at the front end,” he says. “And the better the decision on the front end, the better everything will play out. Because once you make a decision, because of cognitive bias, people often become very wedded to that initial decision. You can call it tunnel vision, confirmation bias, expectancy bias, whatever…but it’s very common.”

New Jersey set aside the Manson test in August 2011. Now eyewitness identification procedures must be captured by cameras. New Jersey judges also must hold hearings—mid-trial if necessary—to weigh fairness when a defendant presents evidence that an identification procedure was unfairly suggestive. And judges must convey to juries that memory is imperfect and that recall can be wrong or distorted. Jury instructions must explain factors that may affect identification dependability, including lighting, poor eyesight, the length of an encounter, whether a witness was under the influence of drugs or alcohol and whether a weapon was being brandished.

Plus, studies show people have more trouble differentiating faces of races not their own and more mistakes happen in cross-racial identifications. Innocence Project research found that to be the case in 53 percent of mistaken-identification cases where the race is known.

The Innocence Project wants states to mandate uniform procedures that include recording lineup proceedings and having blind administration: lineups with pictures or people shown one at a time by officers who don’t know if a suspect is even present. And it recommends witnesses write “confidence statements” immediately after they view a lineup, expressing—in their own words—their level of faith in any identification.

In 2006, a year-long field study conducted by Illinois state police seemed to contradict earlier research, which consistently found fewer mistaken identifications if eyewitnesses view lineup participants one at a time when making identification decisions. But the Illinois study’s design was deemed flawed, more research followed, and a recent study conducted by the American Judicature Society has added to earlier research showing fewer errors in lineups that are sequential rather than simultaneous.

Specifically, it found that viewing lineup participants singly rather than simultaneously—where witnesses must rely on their memories and not on making comparisons—doesn’t significantly reduce the number of accurate positive identifications. Nor does it impede a witness’s ability to make an identification. But it does lead to a significant reduction in witnesses selecting “fillers”—the non-suspects put in lineups. In simultaneous lineups, fillers were picked out 18.1 percent of the time but only 12.2 percent of the time in sequential lineups.

According to eyewitness expert and American Judicature Society study co-author Gary Wells, the future is likely to see a shift to computer-generated lineups designed to reduce bias or investigator influence. Wells also is studying what happens to an eyewitness trying to identify a perpetrator when their memories fail.

“Instead of the person sort of bailing out when memory fails and saying ‘Gee, I don’t know’ or ‘I guess I’m not going to identify anyone,’ secondary processes kick in,” Wells, an Iowa State University psychology professor exploring these issues for 35 years, explained in a statement. “And rather than the primary processes, which are automatic, these secondary processes require more thinking. We call them deliberative. People tend to be more conscious of these. They’re engaged in a process of reasoning and they tend to be more verbal.” As far as misidentifications go, says Wells, these processes “tend to be the dangerous ones.”

Lineup designs, meanwhile, continue to improve, as do legal protections. Thanks to its Supreme Court ruling, New Jersey now has the nation’s toughest guidelines and offers a blueprint—“a new legal architecture,” as Scheck calls it—that may spur nationwide reform.

Shares