MY HIGH SCHOOL CHAPLAIN was the first person to tell me to read Bright Lights, Big City. We were doing an independent study. He told me to pay attention to McInerney’s velocity of voice, but now I suspect he was trying to tell me something else too. I suspect that he was trying to expose me, a would-be writer from suburban California, to New York and its literary scene, equal parts preppy and underground, dapper and grimy. I think he was hoping to give my writing some bite. That he was our chaplain gave him the leverage to be cool, to share secrets, while the rest of the teachers had to act dutiful. I didn’t read the book though. I took pride in the suburbs, in my t-shirt dominated wardrobe. I was sick of hearing about New York. I had some friends from there.

After college, I got a job in San Francisco at a company that owned restaurants and wine stores and wineries. I had enough money to pay the rent and go out on Polk Street. I started to learn about wine. I befriended a waiter at one of the company’s restaurants. He’d been in a punk band. He sensed that I should be doing something else with myself and one day he stopped by my office and gave me Bright Lights, Big City.

I didn’t like the way this book was following me around. I get out of college and meet one literate person and here’s the book he gives me. This was in 2004, 20 years after Bright Lights burst onto the scene. I didn’t like that I’d been told twice that I had to read it. I was miserable with my job, but taking a sickly sort of pleasure in doing nothing about it. Wine was enough. I thought it was sophisticated, even artsy. Sniffing the glass, decoding my senses, I thought that I was preserving my brain for some time in the future when I’d put it to work again. But I wasn’t quite ready to put it to work yet. I sensed that Bright Lights, Big City would push me to act. I was right. After a few weeks of letting it languish on my bedside table, I picked the book up and tore through it in a sitting.

¤

Bright Lights, Big City made Jay McInerney an instant literary celebrity, and at age 24, he, along with Bret Easton Ellis and Tama Janowitz, became the faces of a new literary brat pack.

For me, Bright Lights, 20 years after its release, felt like a guide to the way young writers should be. His world, it seemed, was the one that I should know if I wanted to write about something worthwhile — a world where high highs and low lows converged in a frenzy that seemed like the answer to my workingman’s doldrums. The chaplain had been right.

The chaplain was right about the voice in Bright Lights too. The book has a torrid, vulnerable, wounded voice, the sound of competing impulses — the narrator’s frequently mentioned desire to lead a quiet life, the narrator’s frequently acted upon desire for “Bolivian marching powder.” The voice is the sound of the narrator’s racing thoughts, the thoughts that have run together and blurred and blocked the memory of his dead mother, blotted out the image of his recently-departed (to Paris) young ex-wife — he cannot remember her face. He cannot bear to think about what he has lost, and so his thoughts churn, and he churns, wading through his days at work in a fog, charging through his nights in the city like a bat on fire.

“You were a good guy. You deserved some of the world’s booty. After you met Amanda and came to New York, you began to feel that you were no longer on the outside looking in. When you were growing up you suspected that everyone else had been let in on some fundamental secret which was kept from you.” This voice is muscular and delicate, hardened and innocent. The second person makes it confrontational and evasive. It’s overly declarative and insecure, like a fighter who’s cocked his fists without bothering to have words first. But most of all, the voice has this massive, over-compensating, flawed energy, the type of energy I felt when I was 22, trying to figure out what to do with the self I had bottled up, with the thoughts that raced between my ears but beyond my reach.

“An old lady with a Macy’s bag sitting across from you looks around as if to ask what the world is coming to between these Dracula Jews and zonked-out Africans, but when you smile at her she quickly looks away. You could start your own group—the Brotherhood of Unfulfilled Early Promise.”

The voice carries the book, but McInerney wields his voice, too, and the way he does so is what pushes the book from good to great. He uses the energy on the page to construct a curtain of static for him to slip the plot behind. With this curtain, he pretends that this is just a book about a troubled young man trying to figure things out. But behind that curtain, he turns the real plot on deft inflections — mentions of the smell of bakeries to setup the need for true sustenance, coworkers with maternal inclinations, the carving of a hole that McInerney eventually fills when, finally, his narrator reckons with the memory of his mother and the wound her death inflicted on him.

After I read Bright Lights, Big City, I felt as if my real reading, my real-life, post-college, non-required reading, had finally begun. And it’s kind of funny, to give so much credit to a slim novel about a coke-addled guy in New York. But I felt like with Bright Lights, I’d finally done away with the mental block I’d put up in high school when the chaplain first suggested it. I’d been nervous to expose myself. I’d been nervous to crack my brain open in the way that would force me to quit hiding.

I read McInerney’s other books. The mediocrity of his follow-up efforts (with the exception, I’d argue, of Story of My Life) has been widely reported. The consensus, it seems, is that McInerney is a man who failed to live up to his potential. A teacher I had said that in Bright Lights McInerney showed us he had a voice, but in later works he showed us he didn’t have a brain. A friend loved Bright Lights but quit on McInerney after Ransom, his dashed-off sophomore effort, and said that McInerney was once a conflicted outsider and then he got successful so he became an unconflicted insider and his writing got boring. A writer I met said McInerney drinks too much and cares about “the scene” more than his work. As for me, I like his later works more than most people I know, but I wouldn’t shy away from admitting that they fail to deliver on the promise shown in Bright Lights, Big City.

¤

If you want to be a writer but you’re not writing, you need to feed yourself some kind of stopgap. You can’t just let your writing brain turn to mush. So you sniff on wine and you do your best to spell it all out. And it’s fun. It feels good. It’s extremely difficult to describe sense of smell. The ephemerality of the endeavor matches your mood. It’s consoling that it can’t possibly add up to anything, that this description won’t wind up on paper, that in the morning you’ll forget what you said, forget the true extent of that sniff, and be back to zero, the metric of your stasis that you feel an oddly compelling loyalty to. This zero has an intoxicating purity to it. But then for me it didn’t stop at wine and the next thing I knew I found myself talking about not just wine but morel mushrooms and porcini dust and then I woke up one day and realized, “What the fuck are you doing, dude? How long can you go on convincing yourself that you care about soufflés and tannins?”

Jay McInerney’s latest book is called The Juice. It’s about wine. This is his third collection of wine writing. His first two were collections of pieces he originally wrote for Home & Garden. This new collection draws from his work for The Wall Street Journal.

McInerney refers to wine frequently in his novels, often as a symbol. Champagne on the table at Christmas lunch towards the end of The Good Life is offered as Rubber Cement, intended to hold a family together. In Brightness Falls, a high-rolling publisher drops a bottle of ’61 Chateau Palmer, and Russell, the gourmand, once an aspiring poet, now engineering a hostile takeover of the publishing house where he’s an editor, remarks that he’s “willing to concede that even the illusion of the good life might occasionally be enough.”

¤

Story of My Life is McInerney’s second-best book. Like Bright Lights, Big City, the story follows youth and cocaine in eighties New York. This time, though, the story is told in the first person from the point of view of a woman. The first person gives McInerney the space to indulge verbal tics, to skip around on the page, to jumble things up. More importantly, perhaps, writing as Alison Poole forces McInerney to resist the urge to write like a smug member of the very world his narrator ogled in Bright Lights, a New York in which everyone either makes a massive amount of cash or does something relevant for literature. In his later work, he does not resist this urge, and he starts to sound like he’s saying, “I am a man and I know about things! You can trust me because I have sinned but now I’m on top of the world’s best city!” Whereas before, in Bright Lightsand Story of My Life, it’s, “What the fuck is this place New York and what about my good intentions?”

In Story of My Life, Alison Poole is a young woman who attends acting class and dates older men who work in finance. Writing in her voice, McInerney is often quite funny, and when he’s not taking himself too seriously, he’s at his best. “The next thing I know we’re at his apartment, still talking. It’s like we’re a dialogue machine or something. I tell him about my old boyfriends and that I’ve slept with thirty-six guys and I go, how about you?”

As in Bright Lights, the voice is electric and skittish, but it’s also introspective, and delicate. The voice itself provides tension, like it could shatter. Like the person behind these words could collapse at any second.

“So much for my education. Blanks that never got filled in. None of the above. Story of my life.” The voice makes teeming youth — the sleeping around, the drugs, the late nights, the schemes to get money — feel sad.

“And I’m thinking, boyfriend? Why did I say boyfriend? What’s the matter with me? I’m totally in lust.”

Writing in the second person in Bright Lights, McInerney creates this massive amount of static and frees himself to manipulate the plot behind it. In Story of My Life, the voice serves a similar purpose — this time to throw static between Alison Poole’s sound and Alison Poole’s self. Behind this fast-living, quick-witted schemer from Virginia is a vulnerable, sad young woman. And behind all the sex and drugs, the reader glimpses a worldview that’s both wholesome and sentimental. We get the sense the author believes Alison would recover, would return to herself, if only her mom or her dad or any one of her friends or lovers would stop for a second and give her a hug.

¤

The best place to find the clues as to what went wrong for McInerney are in Brightness Falls and The Good Life. These books share the same cast of characters, and they both focus on the collapse of the good life, or, the indictment of the good life, or the indictment of the life that Alison Poole and Bright Lights’ unnamed narrator are helpless but to pursue.

In Brightness Falls, Russell, the gourmand, the book editor, takes advantage of a frantic atmosphere on Wall Street to enlist an investment banker and a corporate raider to try to take over his publishing company. The idea is that greed corrupts this onetime aspiring poet, now successful book editor, and everything goes to hell.

In The Good Life, two married couples are bored with each other. The plot follows the dalliance between Jeff, a onetime investment banker, now aspiring novelist, and Corrine, Russell’s wife, a onetime stockbroker who has a good heart. Jeff and Corrine seem to be destined for true love, but things don’t work out.

Brightness Falls and The Good Life fail because they don’t deliver the indictment that their setups demand. Rather than deliver a decree on the good life, McInerney resorts to cheap plot devices, a world apart from the voice-enabled light touches of Bright Lights, Big City. In Brightness Falls, the plot feels cribbed from an airport financial thriller, and it feels this way because, being unable to deliver his indictment, and being pigeonholed by the sobriety of his third person voice, his story has nowhere to go but into an excess of plot. “Ok, ok, ok,” you’re thinking to yourself, as you flash through moments of McInerney brilliance, but then, “Shit! Stuff is happening! Stuff is happening again! Why all the affairs and rehab and Wall Street when all I want to know is where my good man Jay Mac went!”

In The Good Life, he does the same thing with a love affair that could only be described as basic and uninspired, despite being set against the backdrop of September 11th. At the end, I threw both books down in frustration.

¤

One of the many problems with Brightness Falls and The Good Life is that McInerney was never writing about the good life to begin with, so in a sense he’s attempting to indict something that was never even his main concern. In Bright Lights and Story of My Life, he was writing about youth. The sadness in those books is not that these young people have flawed notions of what the good life is. The sadness is that they’re young, and that youth is painful and traumatic and lends itself to idiotic decisions, and that youth is going to shatter and crash and come to an end. All the coke and money and society references in both Bright Lights and Story of My Life aren’t necessary. What’s necessary are the voices of these young people, the confusion, the doubt, this combustible coupling of energy and aimlessness. The coke and money are enablers of this energy — they exaggerate it. But in the end, he’s writing about something far more powerful than a couple of enablers, and judging by his later books, it seems like he doesn’t even know it. When McInerney says that he’s writing about the good life, as he does in Brightness Falls, in The Good Life, and in his wine writing, he’s cheating. He’s denying that, when he was young, he was writing about something bigger. Maybe he thinks that his meditations on the good life constitute some big moral concern. In his novels, McInerney hints at the impact of a good bottle of wine — he sets up the symbol; he puts it on the table, as if to make some kind of promise. But in his wine writing, he writes about what this wine tastes like. And fuck, I don’t really care what ’61 Chateau Palmer tastes like. I want to know about the spell it casts on Jay McInerney before he even pops the cork.

¤

In part thanks to Bright Lights, Big City, I got over my t-shirts and came to New York. I’d decided that if I wanted to write, I had to try the place. I moved there in 2008. I had, by now, quit my serious job in favor of less serious day jobs so that I could work on a novel. At first I lived on a friend’s couch. This friend, at 26, was running a hedge fund.

In Bright Lights, Big City, a coworker at McInerney’s fictionalized New Yorker advises the narrator, “Write about [business.] That’s the subject now. The guys who understand business are going to write the new literature.” In Story of My Life, Alison Poole observes, “[Artists] hardly ever talk about their work, they’re always talking about the stock market or something like they’re trying to convince you they understand the real world […]” In Brightness Falls, the poet merges with the banker; in The Good Life, the former banker falls for the wife of the poet.

Living with my friend, I suppose I saw a few scenes worthy of McInerney — former Ivy League athletes playing Never Have I Ever for lines of cocaine, a 10 thousand dollar bank roll in my friend’s sock drawer (I was looking for his porno DVDs…). But really, aside from our shared but fading past, we didn’t have that much to say to each other. I didn’t care about his all-night phone call to “his guy” in Germany about something having to do with Volkswagen, and the day I read him few pages from my book, he listened politely.

I needed to get out of there. I needed a job, and I found one at a wine store on the Upper West Side that specialized in Riesling. (“Your sommelier knows that German Riesling in its semidry form currently represents the best white wine value and that it’s the most food-friendly wine on the planet.”) I ran deliveries and worked the register. I drank in the back room. I rode the subway back to Brooklyn with that warm kind of wine drunk that didn’t seem to leave me with such bad hangovers, and now that I was writing, I didn’t need wine to keep my brain alive, so I was free to enjoy it again, to sniff it without an agenda.

Drinking wine without an agenda, as it turns out, is exactly what McInerney advises. “American wine lovers need to broaden their vision and relax: to see wine as just another aspect of the well-lived life.” He decries the American tendency to think too hard about wine, to be monomaniacal about it, and suggests that we drink to enjoy it rather than treat it as if it were science homework. And before I get any further, let me just say: Jay McInerney is one hell of a wine writer. Wine is complicated and technical. But he makes it so easy to read about. He weaves together the juice, the places, the people, the stories without appearing to expend any energy. He makes it feel perfectly natural to read about oxidation and yeast and all kinds of stuff that, coming from anyone else, would put me to sleep.

¤

Model Behavior might be McInerney’s trickiest book to make sense of. With quick chapter breaks and irreverent chapter titles (“An Okie Abroad”, “How To Get Your Beau To Pop The Question”), it’s got the frenetic energy of Bright Lights. It’s funny, and free of the propriety that damns The Good Life and Brightness Falls — in one memorable scene, the narrator’s father pulls his dick out in a restaurant. It’s personal and introspective. And the plot’s great — a guy gets left by a model and is left to deal with a hilariously vapid sort of heartbreak.

Yet, I couldn’t put down Story of My Life or Bright Lights, but I spaced out all the way through Model Behavior. I recognized the energy, the introspection, McInerney’s totally redemptive self-satire — the narrator writes celebrity puff for a magazine. But I wanted him to push harder. I wanted him to put himself on trial.

¤

In all three of his wine books, at first I was looking for clues to McInerney’s personality. But his wine writing is so good that a third of the way through each of them I was making lists of the bottles I want to try. I flew to Chicago after reading Bacchus and Meand went out to dinner with friends. One of my friends gets migraines from wine. The other drinks bourbon and beer. I ordered an expensive bottle of Chianti. (“Like burgundy, Chianti complements a far greater range of food than most wines made from those two slightly arrogant and cosmopolitan grapes, [Cabernet and Merlot].” My friends were polite enough to drink a small glass each. I got drunk. After reading McInerney, I had to drink some. I couldn’t stop myself.

McInerney restores wine to its natural place on our table; he recovers it from the realm of hard-sniffing monomaniacs. He makes drinking excellent wine feel like the right way to live. He makes you want to drink. I spent all my time reading his wine writing wanting to get drunk. I went out to the new restaurant in my neighborhood, Franklin & Company in East Hollywood, and started with a Gruner Veltliner (“Besides being chlorophyll-friendly, Gruner Veltliner harmonizes beautifully with one other food group: crustaceans.”) and then tried the Au Bon Climat Chard (“I find [Santa Rita Chards like Au Bon Climat] particularly compelling, edgy and extreme, sometimes tasting like turbocharged Chablis…”) and skipped my way down their by-the-glass list, smiling like an idiot, talking to everyone around me, pissing away a hundred bucks as contentedly as possible. Usually I piss away 18 bucks on Bud Light at Birds, the improver’s hangout next door. But drinking good wine is a lot of fun.

¤

Working at the wine store was good but I didn’t make enough money. So, with the help of my wine knowledge, a friend, and a lot of luck, I got a job waiting tables at Minetta Tavern, the restaurant that, at the time, was the latest venture from Keith McNally, the guy who opened The Odeon, the restaurant that appears on the cover of both paperback editions of Bright Lights that I’ve ever owned.

Minetta was a stressful experience, mostly because I barely knew how to wait tables. But I got the hang of it, and the next thing I knew I was waiting on Kirsten Dunst and The Decemberists. I was flirting with that blonde girl from Blue Crush and running into Brooke Shield’s breasts because she’s really tall. I was sleeping with the hostess and getting drunk and staying up until dawn and I wasn’t writing too well and when I saw people I’d gone to school with, I hid and pretended I was somebody else.

¤

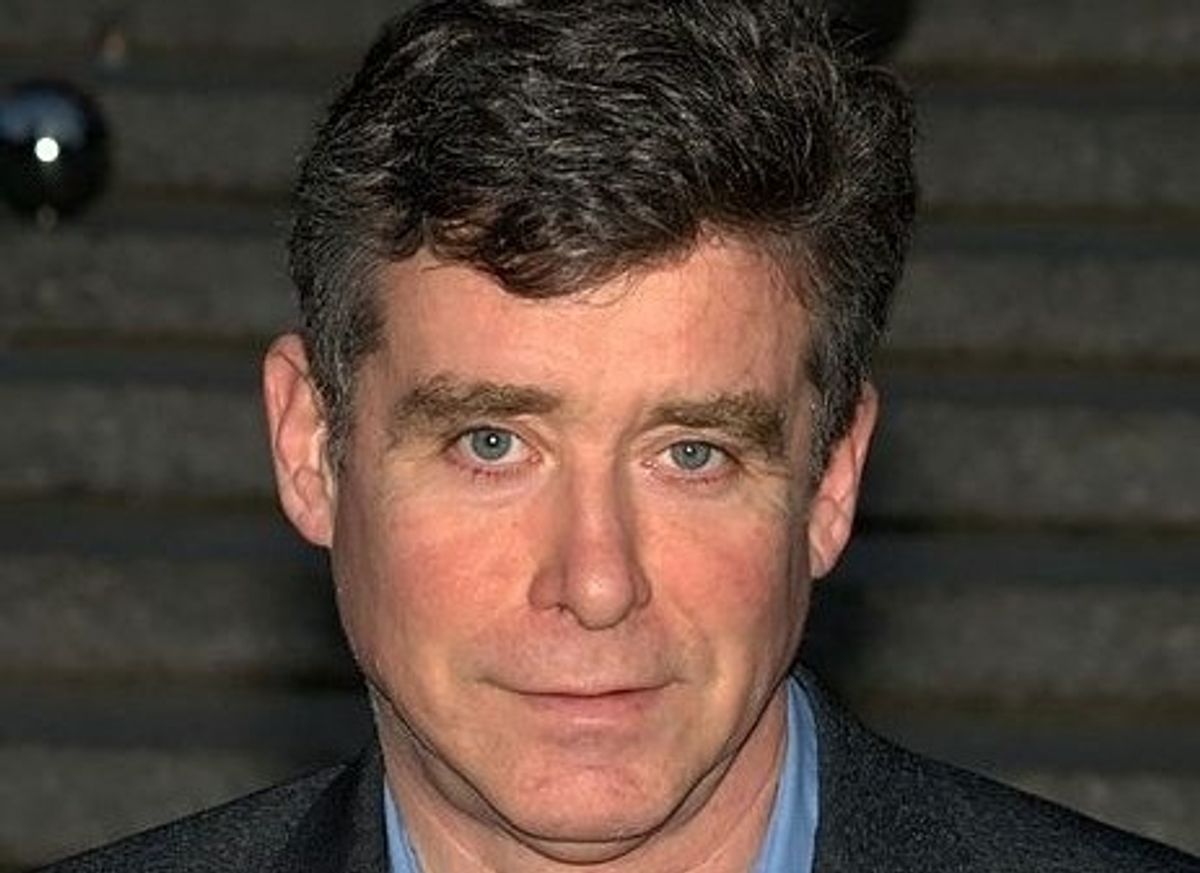

It was table 61, a red booth in between the less desirable bar area and the more secluded back area. The first to arrive was an insanely skinny Asian woman with very long hair. I didn’t know who she was, but one of the managers whispered something about her into my ear. I never knew who anyone was. Everyone was always passing me Post-it notes with names on them, but I’d read these names and they wouldn’t mean anything.

The woman ordered cheap rosé and no food and was soon joined by a rowdy group of middle-aged men. The table was a disaster. They were drunk. They tried to crowd too many people into the booth. They drank only the cheap rosé. They didn’t get any food. They were the single worst table I’d ever waited on. This was one of those tables that make waiters break down at the end of the night and plead with the heavens for reassurance that they’re human beings. The men reminded me of frat boys or something, the type of guys who see getting drunk in public as a way to assert prowess.

They left around one in the morning. I stood by the table and watched them go, dazed and relieved. An older waitress, still an aspiring actress at age 50, came up and said, “Now there goes a cautionary tale.”

I didn’t know what she was talking about.

“That was Jay McInerney. You know, the writer.”

In the dim light and fast pace, I’d failed to recognize him, and now I fell into an internal tailspin of ranting and raving that lasted for the next 12 hours.

¤

I was upset that this guy whose book I’d loved was such a lout. I was mad that someone whose name got brought up within seconds whenever I talked about my own book had abused the power he had over my work. Drunken assholes get the artist’s reprieve when their writing is great. But this guy’s writing wasn’t great anymore. I wanted to scold him, to send him to his room to consider his bad behavior.

And I was mad that the old waitress who called herself an actress thought of him rather than herself as the cautionary table. Hers was the fate I feared for myself, not his. And I was mad that Jay Mac made it easy for her to think that. Before I knew who this guy at my table was, I’d already decided I didn’t like him. I never disliked any strangers. Except the ones at this table. And then, that old waitress told me who he was, and I almost lost my mind. I couldn’t sleep. Over and over I found myself telling some phantom editor or agent why my book was good, and why not to compare it to Bright Lights, Big City, and why Bright Lights, despite what’s inside its pages, was a total sham.

¤

At first I thought I was tired of waiting tables, but really I was tired of New York. So I left. I moved to Milledgeville, Georgia, where I wrote all day and read thick books and when I got stuck on the thick books, I bailed myself out with Jay McInerney. Reading McInerney in Georgia, his work came to feel like an elegy for a phase I was glad to be done with. And, reading McInerney in the South has its charms. He writes about the South a lot. Alison in Story of My Life is from Virginia. The Last of the Savages takes place in the Delta. Jeff from The Good Life recovers from his affair’s fallout in Tennessee. But reading Jay Mac from the distant precinct of the Deep South, his world started to look, maybe, quaint? Like, taking it as self-evident that beautiful women, financiers, and writers made for the sexiest possible conglomerate of people was a tired-out trope?

¤

I met a girl in Milledgeville. We were at a party and I was fucked up out of my mind and I’ll never forget how her entrance sprung me from my stupor, so incredible was her beauty and command of the room. I did not dare talk to her. I knew that if I did, it would be disastrous, garbled as my thoughts were, unsteady was my gait. In the morning, though, I woke up, opened my journal, and saw “Call Lucy” in huge letters with a phone number below.

I called. She was on her way out of town, back to Athens, but we stayed in touch. She moved to New York last Spring. A few weeks ago, on account of a layover at JFK that became a cancelled flight, I spent the night with her, and next Friday, I’m going back. I don’t know what the hell’s going to happen with her, but at least she’s 21 now, so when I pull into town, I can take her to dinner at Minetta and we can legally split a bottle of wine.

I have a fantasy that Jay Mac will be seated right beside me. I still have a lot to say to him, more than I did when I waited on him. But I’m not angry anymore. I know Bright Lights, Big City is the best possible voice-driven post-college young-man-who-wants-to-be-a-writer-in-New-York book outside of This Side of Paradise. I know that what I’m doing now is my own thing. I don’t need Bright Lights, Big City to guide me anymore. And occasional dinners with Southern bombshells aside, I’ve moved on from the young man in New York fantasy. I was always too Californian for it anyway, even if I didn’t know it. But I still have a lot to say to the man.

“Jay,” I would start, “You always believed that the good life was scandalous, and that those who strived for and attained the good life would have to pay a price. But then you got there. You broke through. And instead of having to pay, you realized you were the same guy you’d always been and nobody was going to put you in jail — there would be no trial, there would be no punishment — and you got bored. The problem with your later books is that they’re boring. They’re boring because you’re bored. And you should be writing books about being bored. You should write about yourself. In The Juice, you recall the moment when Winston Churchill asks the much younger Alexis Lichine to do the talking. Well, I’m doing the talking now. And I’m going to read whatever you write either way. But what I want is this — a story about a middle-aged drunk who’s reckoning with the fact that he’s squandered his talent. That is the subject on which you are America’s foremost authority.”

Shares