IN THE OLD DAYS there were angels who came and took men by the hand and led them away from the city of destruction. We see no white-winged angels now. But yet men are led away from threatening destruction: a hand is put into theirs, which leads them forth gently towards a calm and bright land, so that they look no more backward; and the hand may be a little child’s.

— George Eliot, Silas Marner

A recent sociological study found that atheists are America’s least trusted minority. Americans, the researchers concluded, “construct the atheist as the symbolic representation of one who rejects the basis for moral solidarity.” Most Americans, that is, apparently think of atheists not just as people who don’t share their specific beliefs about the existence of a divine being, but as ethical recusants who cannot be trusted.

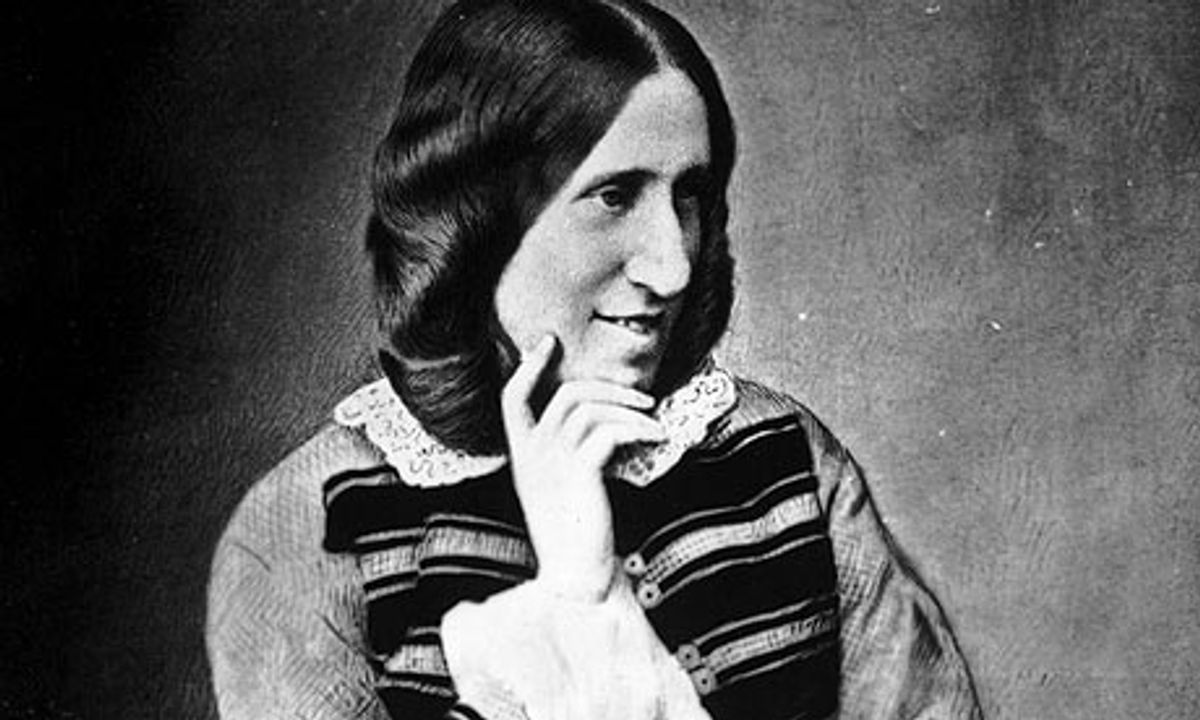

This is not an expert view, only a popular one: no preponderance of evidence supports it, and philosophers can readily explain how it is possible to be good without God (some have even argued it is impossible to be good with God). But prejudices are difficult to dislodge, and science and reason often, paradoxically, prove ineffective tools. Even those of us who tend to agree with “New Atheists” like Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and the late Christopher Hitchens can find their hectoring tone wearying. Perhaps what is needed to help move people past the differences they believe divide them — or, more precisely, past the different beliefs that do divide them — is neither a leap of faith nor a rule of logic, but an exercise of the imagination, a new construction of the atheist that would transform mistrust into sympathy, hostility into fellowship. One of our best allies in such a project is Marian Evans, who by her more familiar name of ‘George Eliot’ was (as noted by one of her contemporaries) “the first great godless writer of fiction.”

Eliot’s irreligion struck many of her contemporary readers as paradoxical. How could she be at once such a stringent moralist and an unbeliever? For, then as now, religion was popularly believed to be the essential foundation of ethics. And why was it, if she didn’t believe in God, that her fiction is deeply and often sympathetically attentive to people’s religious lives — or, at any rate, to their lives as religious people?

That seemingly fine distinction is actually a good clue about how these apparent inconsistencies resolve. A devout evangelical Christian in her youth, Eliot gave up her faith due to her studies in science and in the German “higher criticism” of the Bible, which examined it as a historical rather than a sacred text. The first conspicuous result of her changing perspective was the episode she called her ‘Holy War,’ in which she defied convention in general and her family in particular by refusing to attend church: “I could not without vile hypocrisy and a miserable truckling to the smile of the world,” she wrote to her outraged father, “…profess to join in worship which I wholly disapprove.” Atypically among holy wars, this one ended in compromise, with Marian agreeing to maintain at least a superficial conformity. She eventually came to see her initially inflexible stance as a sign of immaturity, of an egoism that too readily sacrificed fellow feeling to rigorous principle: “The first impulse of a young and ingenuous mind is to withhold the slightest sanction from all that contains even a mixture of supposed error.” Years later, she was to write to a friend, “As for the ‘forms and ceremonies,’ I feel no regret that any should turn to them for comfort, if they can find comfort in them: sympathetically, I enjoy them myself.” But while she reconsidered the relative importance of form and feeling, she made no concessions to the Christian doctrines she had renounced.

Though convinced that there was no divine authority, Eliot did not believe that we could not therefore find and follow moral imperatives. Instead, she sought them in secular, rather than sacred, texts, and appealed to logic, philosophy, and her own conscience rather than to God. A dedicated student of German philosophy, she was influenced particularly by Ludwig Feuerbach in her recasting of so-called “Christian” values as humanistic ones. In his 1841 book Das Wesen des Christentums (which Eliot translated as The Essence of Christianity twelve years later), Feuerbach argued that “God” is not an external being but a projection of our own best qualities. Thus, in worshipping God people are, in effect, worshipping themselves: everything they credit to supernatural forces is really the result of the human capacity for generosity, sympathy, and love (on the side of virtue), and for egotism, hatred, and cruelty (on the side of vice).

On this view, religious belief is not so much a “delusion,” as Dawkins would have it, as a confusion, a mistaken attribution; it’s not, as Hitchens wrote, that “god is not great” but that what we call “God” is only as great, or as terrible, as we are. Ultimately all of Eliot’s fiction shows that the real object of our moral hopes and fears should be ourselves. But because Eliot understands religion as the form through which many people have, historically, expressed their best moral impulses, she shows none of the disdain towards believers qua believers that some find alienating in the work of these “New Atheists.” In fact, Eliot believed that “the idea of a God who not only sympathizes with all we feel and endure for our fellow-men” could “pour new life into our too languid love, and give firmness to our vacillating purpose.” Unlike Alain de Botton, whose “religion for atheists” preserves the forms of religious observance while casually dismissing the content, Eliot offers an atheism for believers — provided their religion leads them above all to “sympathize with individual suffering and individual joys,” which, as she asserts in one of her letters, she considers the only real measure of our moral progress.

¤

Of course, Eliot was not a philosopher but a novelist, and it’s significant that she chose to make the case for her secular ethics not through polemics or disquisitions but through her fiction. Art, she argues in “The Natural History of German Life,” a famous early essay, is “a mode of amplifying experience and extending our contact with our fellow men beyond the bounds of our personal lot”:

The greatest benefit we owe to the artist, whether painter, poet, or novelist, is the extension of our sympathies. Appeals founded on generalizations and statistics require a sympathy ready-made, a moral sentiment already in activity; but a picture of human life such as a great artist can give, surprises even the trivial and the selfish into that attention to what is apart from themselves, which may be called the raw material of moral sentiment.

For Eliot’s purposes, ethics and aesthetics are inseparable. All of her novels, which she called “a set of experiments in life,” show her trying out different literary strategies to extend our sympathies. Her greatest, Middlemarch, exemplifies on a grand scale her fusion of form and philosophy. An extensive web of interconnected characters and plots, Middlemarch achieves an extraordinary resonance through the comments of its wryly intrusive narrator, but also through its complex manipulation of point of view, which makes palpable the moral value of attention to what is apart from ourselves. The same technique, however, insistently reminds us that it is we, not some supernatural force, who make life better or worse for “our fellow men.”

Middlemarch is a tremendous achievement; it’s no wonder that Virginia Woolf called it “the only English novel written for grown up people,” or that Henry James declared that it “sets a limit to the development of the old-fashioned English novel.” But Eliot’s humanistic ideals are at their most accessible in an earlier work, Silas Marner, a tiny masterpiece that beautifully illustrates her method of philosophical fiction. A moving fable of loss and redemption, Silas Marner is also a shrewd commentary on the ways supernatural explanations get superimposed on wholly natural events. The gratifyingly sentimental conclusion of the novel moves us past these abstractions, however, as Eliot believed art must do, drawing on the affective power of fiction to convert us to faith, not in God, but in humanity.

The basic plot of Silas Marner is simple enough. Framed for theft (by a friend who also steals his fiancée) and suspended from membership in his church, Silas Marner finds himself bereft at once of belief in man and in God. Exiled from his home, he settles near the remote village of Raveloe, where he ekes out an isolated existence as a weaver. His life is reduced to “the unquestioning activity of a spinning insect”; his only comfort and companionship comes from the growing pile of gold coins with which he is paid for his cloth, which becomes the governing purpose of his days.

He might have continued indefinitely in this blighted state if his life had not intersected with another’s, this one damaged not from without but from within. Dunstan Cass, a child of privilege, relies on good family and good luck to protect him from the consequences of his actions. While Silas hoards, Dunstan squanders, and he entangles his weak-willed brother Godfrey in his web of debt and deceit. Making his way home one foggy night after recklessly destroying the horse that was to restore his and his brother’s fortune, Dunstan passes Silas’s cottage and steals the miser’s unguarded gold. Silas’s grief when he finds his treasure missing is wrenching, but the theft has a silver lining: after years of estrangement, Silas is propelled by his despair into the “strangely novel situation of opening his trouble to his Raveloe neighbours.” Thus he takes a tentative first step back into the human community.

It takes a second home invasion, however — this time leaving, rather than taking, something precious — to complete the transformation. This time the nocturnal wanderer is a golden-haired child who appears inexplicably on his lonely hearth. When Silas’s weak eyes first glimpse her bright curls, he thinks it’s “his own gold — brought back to him as mysteriously as it had been taken away!” The child’s mother is found dead by the road and no other claim is asserted to counter Silas’s unexpected declaration, “I’ve a right to keep it.” So he becomes the adoptive father of the little girl he names “Hephzibah” and calls (more kindly) “Eppie.”

In a clear parallel to another little child who arrives mysteriously and becomes an instrument of earthly salvation, Eppie is the means by which Silas’s redemption is completed. She does not teach him how to live and love through sacrifice and death, however. Rather, she reconnects Silas to the world and the people around him: “the child created fresh and fresh links between his life and the lives from which he had hitherto shrunk continually into narrow isolation.” While the story of that other child turns on miracles, Eppie’s influence is entirely natural: “Eppie was a creature of endless claims and ever-growing desires, seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and living movements; … and stirring the human kindness in all eyes that looked on her.”

Caring for Eppie prompts Silas into precisely that “attention to what is apart from himself” that Eliot considered essential to moral life: “The gold had kept his thoughts in an ever-repeated circle, leading to nothing beyond itself; but Eppie was an object compacted of changes and hopes that forced his thoughts onward.” As she flourishes, so does Silas, redeemed by her presence from his miserly misery:

The little child had come to link him once more with the whole world. There was love between him and the child that blent them into one, and there was love between the child and the world—from men and women with parental looks and tones, to the red lady-birds and the round pebbles.

This is the stuff, as the novel’s heart-warmingly sentimental conclusion shows, from which happy endings are rightly made.

But touching as Silas Marner is, heart-warming sentimentality is very much the means, rather than the end, of the novel: our emotional engagement moves us to feel satisfaction at a conclusion that is much more subversive than it seems. Like so many Victorian novels, Silas Marner ends with a wedding, but en route we have been schooled less in romance than in philosophy. Though we sympathize with and celebrate the characters’ happiness, the narrator’s commentary throughout the novel has created a thin but resilient analytic layer between their experience and ours. Silas Marner’s journey is an emotional one, but Silas Marner’s, and ours, is also an intellectual one, a movement towards readiness for a world without God.

¤

It is the stories we tell ourselves about the world that interest Eliot, and that she subtly influences us to change. From its first page, Silas’s story is embedded in a discussion of storytelling itself, one that highlights the ways people make sense of what they see, and how they fill in the gaps left by what they can’t see themselves, or can see but can’t understand. Before we meet Silas himself, for instance, we learn of the general class of itinerant weavers to which he belongs. These men arouse misgivings in the villages they pass through because their origins are unknown: “how was a man to be explained unless you at least knew somebody who knew his father and mother?” To the villagers, “the world outside their own direct experience was a region of vagueness and mystery.” This provincial ignorance is a breeding ground for superstition: no doubt, the local shepherd thinks, the unfamiliar trade of weaving could not “be carried on entirely without the help of the Evil One.” Limited knowledge, that is, does not prevent people from interpreting what they see — only from interpreting it accurately.

Silas becomes our case study in this process of mistrust and misinterpretation. Like anything and anyone “that was at all unwonted,” he is seen through a haze of uninformed suspicion. To the villagers of Raveloe he has “mysterious peculiarities which corresponded with the exceptional nature of his occupation, and his advent from an unknown region called ‘North’ard.’” His reclusive habits, odd appearance and occasional inexplicable “fits” all add to their wariness. Silas’s skill at his work protects him from persecution, though not from hostility, but he also owes his security to the “vague fear” that he has not just unknown origins but also unnatural backing.

We know otherwise, however, because the narrator tells us in detail “the history of Silas Marner until the fifteenth year after he came to Raveloe.” In place of the villagers’ dubious speculation, she gives us an explanation rooted in her theory of determinism, which, as Eliot scholar George Levine explains, “entailed a total commitment to the notion that every action has its causes, and only by a meticulous examination of those causes can any action be seen as comprehensible.” When you know enough, there’s not only no need to guess, but no need for hypotheses outside of nature. That such full understanding often eludes mere mortals explains but does not justify otherworldly theories, especially as these inhibit sympathy and responsibility, for Eliot the twin pillars of morality. Man, Feuerbach protested, thanks God

for those benefits which have been rendered to him even at the cost of sacrifice by his fellow-man. … He is thankful, grateful to God, but unthankful to man. Thus is the moral sentiment subverted in religion!

Silas Marner affirms that gratitude and blame are properly directed at our “fellow-man.” There’s nothing Satanic about Silas: he left his home because his friend betrayed him and his colleagues cast him out; he keeps aloof from his neighbors because he’s depressed; and he suffers from cataleptic seizures, not demonic possession. Because we know all this, we watch with amused detachment when Silas’s actions and motives are construed by the unscientific people of Raveloe as evidence of his unnatural affiliations, and we appreciate their gradual enlightenment once they are thrown into closer contact with Silas:

Instead of a man who had more cunning than honest folks could come by, [...] it was now apparent that Silas had not cunning enough to keep his own. He was generally spoken of as a ‘poor mushed creature,’ and that avoidance of his neighbours, which had before been referred to his ill-will, and to a probable addiction to worse company, was now considered mere craziness.

Closer study, that is, yields better data, which in turn generates a narrative that is both closer to the truth and more conducive to sympathy.

The theft of Silas’s gold is treated in a similar way: speculation and misinterpretation flourish among the characters, but our comprehension is fuller thanks to the narrator’s “meticulous examination” of causes. We know the thief’s identity and history; we see how motive, means, and opportunity combine to create an utterly human crime — yet Silas, not knowing what we know, wonders whether the gold was taken by “a cruel power that no hands could reach, which had delighted in making him a second time desolate,” and the first explanation at the Rainbow is that “this ill turn had been done to Marner by somebody it was quite in vain to set the constable after.”

Eppie’s arrival, too, is no mystery to us. “The child was come instead of the gold,” is all Silas can think; “It’s been sent to you,” says his kindly neighbor Dolly Winthrop. But we know that Eppie is the daughter of Godfrey Cass and poor opium-addicted Molly, who struck out into the winter night in “a premeditated act of vengeance” to demand acknowledgment as his wife. We follow Molly’s journey as we followed Dunstan’s, the literal movement rendering tangible the paths that connect individual lives into complex histories. It’s opium, not fate or divine intervention, that overcomes her and causes her to let go her child, who then “toddle[s] through the snow … to the open door of Silas Marner’s cottage” and is lulled to sleep by the comforting warmth. There’s nothing miraculous about her arrival, in other words. But is her plight, or Silas’s startled joy, any less moving because of that?

As the story continues, the characters often infer the governing presence of some higher being: “There’s good i’ this world,” Silas says reflectively to Dolly, “I’ve a feeling o’ that now; and it makes a man feel as there’s a good more nor he can see, i’ spite o’ the trouble and the wickedness … there’s dealings with us—there’s dealings.” We’ve seen, however, that those dealings are between ordinary, imperfect men and women. Dunstan, Godfrey, Silas’s treacherous Lantern Yard friend: they all make decisions that hurt those around them. Each of them also lets luck stand in for justice, trusting to chance or taking chances, thus abdicating their own moral responsibility. And that is really the nub of the problem, and the reason Eliot’s novels typically direct our attention not forward, prophetically, but backwards, historically. In order to act morally we need to understand both the causes and the consequences of our actions — or, more generally, we need to understand that all actions have both causes and consequences. The more we trust to luck or put our faith in God, the less focused we are likely to be on ourselves as sources of what, in Middlemarch, Eliot calls “the growing good of the world.” Our mental effort, then, should be dedicated to discerning the complex operations and interactions of nature and society and personality: our perspective should be scholarly, not visionary.

The principle that deliberate human action is morally central explains why, though Silas Marner ends with Eppie’s wedding, its dramatic climax is not the marriage proposal but a proposal of another kind: Godfrey’s assertion of his “natural claim” on Eppie, and his offer to “have Eppie, and treat her in every way as our own child” — which, after all, she is. But biological parentage is in its own way accidental. It is certainly not destiny: Godfrey’s “natural claim” does not outweigh the conscious choice he made not to be Eppie’s father, as Silas, “not without a touch of parental fierceness,” is quick to argue:

“then, sir,why didn’t you say so sixteen year ago, and claim her before I’d come to love her, i’stead of coming to take her from me now, when you might as well take the heart out o’ my body?”

Godfrey’s changed mind does nothing to change his past deeds. Deeds, indeed, are a more burdensome progeny than children, for as Eliot observes rather grimly in Romola, “children may be strangled, but deeds never: they have an indestructible life both in and out of our consciousness.”

In contrast to Godfrey, Silas chose to care for Eppie, without obligation, duress, or promise of subsequent reward. The people of Raveloe believe “he had brought a blessing on himself by acting like a father to a lone motherless child,” and Eppie’s presence is indeed a blessing for Silas. But that’s because she is a real child with needs he can meet and affection he can return, and because he acts responsibly and lovingly. Silas and Eppie earn, they are not sent, their happy ending, and therein lies the moral of the story.

It’s a happy ending here on earth, too: one reason it’s so important to take responsibility for helping or harming each other, after all, is that in a material universe there are no rewards or punishments to come later. The idea of future rewards for virtue, Eliot wrote in a characteristically rigorous 1855 review of an ethically unsatisfactory novel, “undermines all true moral development by perpetually substituting something extrinsic as a motive to action, instead of the immediate impulse of love or justice.” In another review, of a poet whose verses proclaimed that belief in immortality is our only protection against self-interest, she offered an eloquent rebuke of such ‘other-worldliness’:

It is a pang to me to witness the suffering of a fellow-being, and I feel his suffering the more acutely because he is mortal—because his life is so short, and I would have it, if possible, filled with happiness and not misery.

¤

Eliot was clearly capable of making her case through direct argument. But arguments are rarely won through reason alone: as she observed in that early essay, “generalizations and statistics” aren’t usually enough to surprise us into new ways of thinking. Fiction, however, can carry us imaginatively across many different boundaries, and through our vicarious experience we can lose our fear of the alien and the unknown. By drawing us in emotionally, fiction can also help us feel acutely the suffering of our fellow-beings, and thus chafe against any teachings that inhibit our attempts to relieve them.

“It seems to me,” the novelist MarilynneRobinson has said, “that anything that is written compassionately and perceptively probably satisfies every definition of religious whether a writer intends it to be religious or not.” Like Eliot, Robinson asserts continuities between belief and unbelief, but she does so by identifying as religious what Eliot saw as intrinsically human feelings. Call them “religious” if you like, Eliot might have said. “I have no longer any antagonism,” she wrote in her letters,

towards any faith in which human sorrow and human longing for purity have expressed themselves; on the contrary, I have a sympathy with it that predominates over all argumentative tendencies.

Against those “argumentative tendencies” that seem to define the cultures of atheism and religion alike today, Eliot offers us novels like Silas Marner, novels that express her own faith that with sufficient understanding and attention to what is apart from themselves, people can be their own salvation. It’s a vision at once rigorous and humane, one that could lead us to a new, shared “basis of moral solidarity.”

Shares