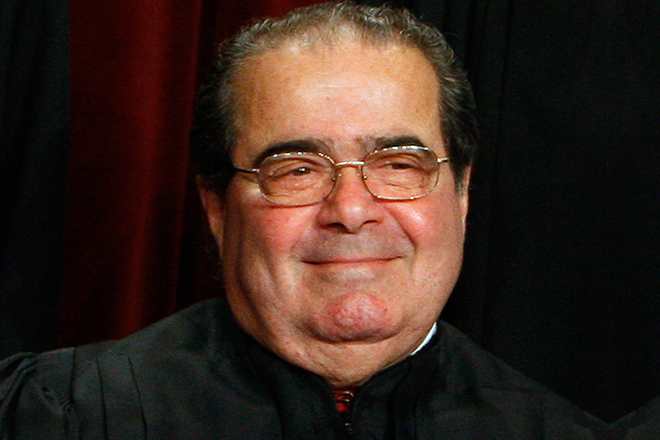

The Supreme Court is hearing arguments tomorrow in a case that is likely to result in a ruling that race-conscious affirmative action programs are unconstitutional. One thing is certain: Antonin Scalia will vote to strike down such programs because, according to him, the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits them.

This doesn’t get said enough: Scalia is an intellectual fraud who uses a phony methodology to get whatever judicial outcomes align with his political preferences, at least in cases involving issues such as affirmative action, where those preferences are strong.

Scalia’s method is what he calls “textual originalism,” and it’s supposed to work like this: When interpreting a legal text, judges should give that text the meaning it had at the time the law was enacted – and the meaning it had (and continues to have) is the meaning the people who enacted the law thought it had at that time. Thus, as he informed an audience earlier this month, questions about whether the Constitution prohibits the death penalty or laws criminalizing abortion or same-sex relations are easy to answer:

The death penalty? Give me a break. It’s easy. Abortion? Absolutely easy. Nobody ever thought the Constitution prevented restrictions on abortion. Homosexual sodomy? Come on. For 200 years, it was criminal in every state.

But wait – doesn’t this method require a judge who applies it to consistently find that affirmative action programs are permitted by the Constitution? Indeed it does. After all, the people who enacted the Fourteenth Amendment didn’t think it prohibited good, old-fashioned segregated schools, let alone affirmative action. (Legal segregation continued in America for nearly a century after the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment – indeed Washington DC’s own schools were segregated at the time the Supreme Court declared such segregation illegal in Brown v. Board of Education).

How does Justice Scalia, principled champion of textual originalism, get around these extremely awkward historical facts? It turns out that this, too, is “easy” enough for our clever jurist: He merely declares that the people who enacted the Fourteenth Amendment were outlawing “racial discrimination.” Mysteriously, their specific expectations at the time about things like whether schools would continue to be segregated are no longer relevant.

This is one of the oldest legal tricks in the book. If you want to find a law unconstitutional, simply define the relevant constitutional text at a sufficiently high level of abstraction without regard to what the enactors of the law thought they were doing. By contrast, if you want to uphold a law against constitutional challenge, interpret the constitutional text in the narrowest historical terms.

Thus, in the context of abortion or criminalizing same sex relations, the relevant question, according to Scalia, is whether the enactors of the Fourteenth Amendment believed they were preventing restrictions on abortion or prohibiting the criminalization of same sex relations. But in the context of affirmative action, the question suddenly becomes not whether the enactors thought they were prohibiting the use of racial preferences, but whether the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits “racial discrimination,” broadly defined.

Scalia’s most stunning employment of this sort of egregious methodological flip-flopping was in Bush v. Gore – a case in which he adopted a radically anti-originalist interpretation of the Constitution that allowed him and four other Supreme Court justices to hand the 2000 presidential election to their preferred candidate.

Now an interesting question is whether Scalia has any self-awareness that his supposed dedication to textual originalism is as phony as a three-dollar bill. The degree of that dedication is invariably inversely proportional to how much he cares about the outcome of a particular case. Consider Scalia’s portrait of the sanctimonious arrogance of the “activist” judge:

He contrasted his style of interpretation with that of a colleague who tries to be true to the values of the Constitution as he applies them to a changing world. This imaginary justice goes home for dinner and tells his wife what a wonderful day he had, Scalia said.

This imaginary justice, Scalia continued, announces that it turns out “the Constitution means exactly what I think it ought to mean.” No kidding.

That Justice Scalia can say such things with no hint of irony tells us quite a bit about sanctimony, arrogance and activist judging.