The five finalists for the 2012 National Book Award for fiction make for an exemplary shortlist — and I say that even though none of them is likely to end up on my own best-of list at the end of the year. There's a good variety: a popular short-story collection by the recent MacArthur recipient Junot Diaz ("This is How You Lose Her"), a debut novel about the Iraq War ("Yellow Birds" by Kevin Powers), a small-press title (Dave Eggers' "A Hologram for the King"), an overlooked midlist book (Ben Fountain's "Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk"), even the 14th novel by an established writer, Louise Erdrich's "The Round House" — precisely the sort of title people don't bother to read because they assume they already know what's in it.

What you won't find, however, is the book that many, many literary fiction buffs read and loved in the past six months: Gillian Flynn's best-selling crime novel, "Gone Girl." Flynn's book is inventive, shrewd, mercilessly observant and stylishly written — qualities that are very welcome and likely to be celebrated in a literary novel. Her theme, the dissolution of a marriage in recession-era America, is substantive. Her technique (which, at the risk of spoilage, I'll vaguely refer to as unreliable narration) is sophisticated. But let's face it: "Gone Girl" is still considered a crime novel, and the likelihood of any work of genre fiction being seriously considered for a major literary prize still seems as far-fetched in 2012 as the election of a black president looked to be in the 20th century.

The National Book Awards is no more to blame in this respect than any other prize: The Pulitzer, the Booker and the National Book Critics Circle prizes have all refrained from honoring any title published within the major genres. (True, some observers considered "Snowdrops" by A.D. Miller — shortlisted for the Booker last year — a crime novel, but the entire 2011 Booker selection process was enveloped in controversy arising from the judges' much-denounced remarks on behalf of "readability.") The genres have their own prizes, but the most prestigious of the awards remain the private reserve of literary fiction.

Yet we live and read at a time when the lines between genre and literary fiction are being persistently rubbed away. The literary quality of the best genre novels is higher than ever, and literary novelists have increasingly embraced elements of the genres in their work. Jennifer Egan won the Pulitzer last year for "A Visit From the Goon Squad," a novel that has elements of science fiction, and it's hard to regard "No Country for Old Men," by one-time NBA winner Cormac McCarthy, as anything other than a thriller. Flynn is only one among a cadre of women writers (along with Tana French, Kate Atkinson and Laura Lippman) who work within the established genre of crime fiction, expanding it into new and more challenging territory.

The traditional objections to genre fiction — that it is formulaic, psychologically inauthentic and indifferently executed — are not without merit, but then neither are the genre fans' familiar retorts that literary fiction is self-indulgent, feebly plotted, overwritten and dull. The average work in any fictional category will be underwhelming; what really counts are the best. I have a hard time seeing why Thomas Pynchon is regarded as an important novelist while Neal Stephenson, who writes in a similar vein but with (to my mind) more intelligence and maturity, is viewed as merely the high end of science fiction.

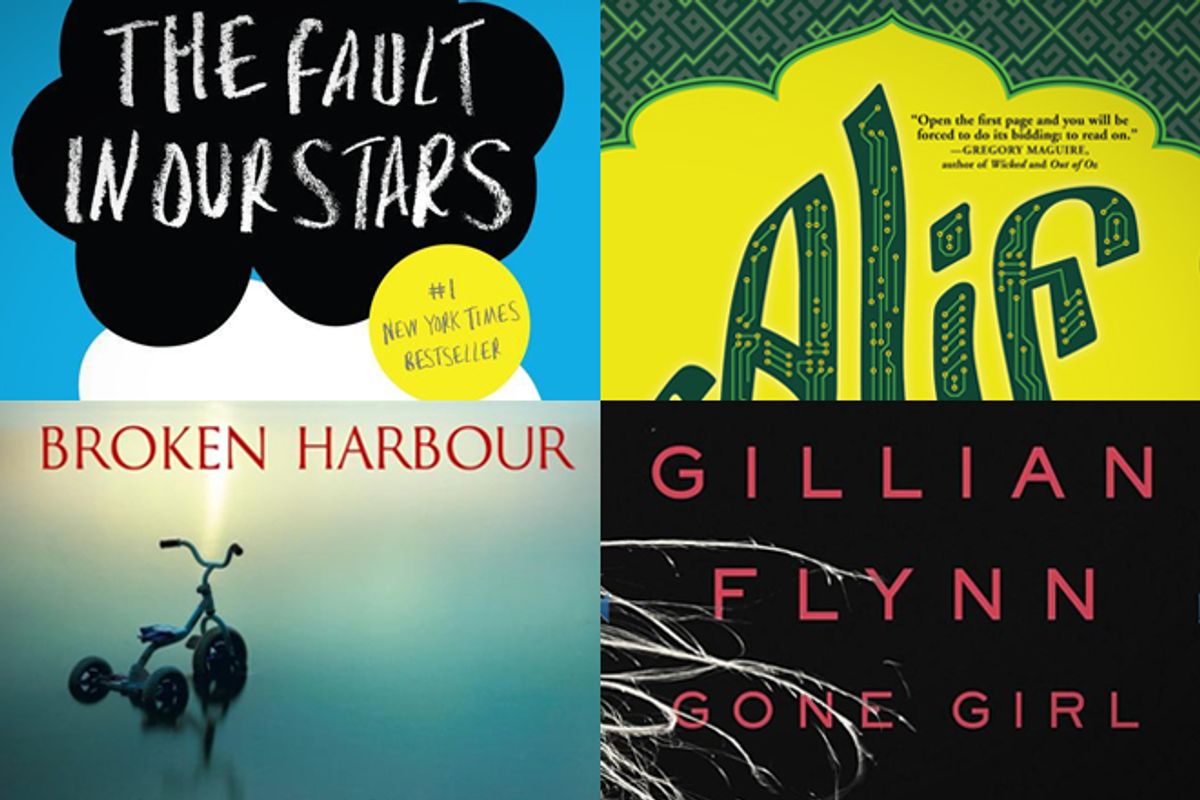

"Gone Girl" has succeeded in jumping the fence, but two of the best books I've read this year will never catch the attention of many readers who would surely love them, and that's solely because of their genres: G.Willow Wilson's "Alif the Unseen," a fantasy, and John Green's "The Fault in Our Stars," a YA novel. Although much of genre fiction caters to escapist wish-fulfillment — a persuasive argument for not regarding it as "serious" — these novels deal with subjects as intractable and consequential as those tackled by the most celebrated books of the year: political repression in the Mideast and mortality, respectively.

Often, genre categories seem more a matter of habit and convenience than anything else. An overburdened prize commitment finds it a relief to disqualify big chunks of possible candidates out of hand. People who prefer to read only naturalistic fiction can elide millennia of Western culture (including everything from "The Odyssey" to "The Tempest") and tell themselves that their taste just happens to coincide with true literary merit. On the other side, aggrieved genre partisans feel justified in ignoring books they might otherwise enjoy simply because the people who like those books don't respect the books that they like.

All of this is very silly, and the first acknowledged work of genre fiction to win a major literary prize will 1) cause an enormous uproar among such mounters of the highbrow/lowbrow barricades as Harold Bloom and 2) open up new vistas of books to readers (and critics) in both camps who have been far too accepting of the old distinctions. They will find that the authors got there first; I've yet to meet a truly interesting literary novelist who doesn't speak of genre writers among the colleagues she reads, admires and has learned from, and vice versa. "Gone Girl" might have been the book to achieve this revolution in the reading public's mind. If the moment has yet to arrive, it's not the books that aren't ready. It's us.

Further reading

Shares