WHEN THE NOBEL PRIZE in Literature is awarded, commentators often wonder if it was given to recognize the quality of the author's writing or for other reasons: jockeying within the committee, a desire to acknowledge a particular genre or style’s importance, the wish to make a political statement — or all of the above.

WHEN THE NOBEL PRIZE in Literature is awarded, commentators often wonder if it was given to recognize the quality of the author's writing or for other reasons: jockeying within the committee, a desire to acknowledge a particular genre or style’s importance, the wish to make a political statement — or all of the above.

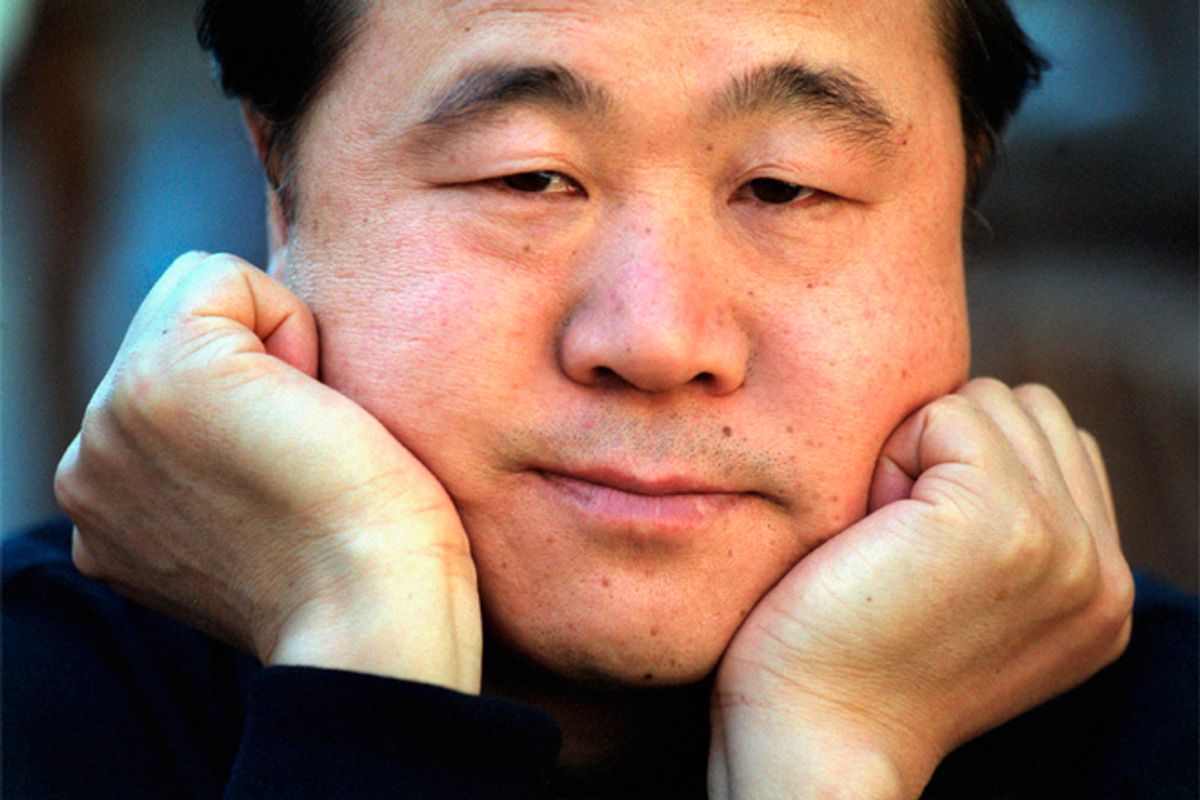

These questions will doubtless be raised about Mo Yan, the latest literary Laureate, but issues specific to China will also come up, such as how he compares to previous winners with ties to that country, like Pearl Buck, who wrote stories set there, and Gao Xingjian, the Chinese writer who won the prize after leaving his country to live and write in France.

To uncover answers to some of these questions and introduce — or reintroduce — Los Angeles Review of Books readers to Mo Yan, whose previous most famous Western exposure was as the author of the story that served as the basis for Zhang Yimou's film Red Sorghum (1987), we turned to Sabina Knight. She teaches Chinese and Comparative Literature at Smith College, and her specialty is contemporary Chinese fiction. A fellow in the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations' Public Intellectuals Program, Knight is the author of The Heart of Time: Moral Agency in Twentieth-Century Chinese Fiction (Harvard, 2006), and, most recently, Chinese Literature: A Very Short Introduction, a lively and wide-ranging work published by Oxford University Press earlier this year.

¤

Jeff Wasserstrom: What was your first thought when you heard Mo Yan was this year's winner of the prize?

Sabina Knight: My first thought was “It couldn’t have happened to a nicer guy.” Mo Yan is a genuine, decent, warm-hearted human being.

JW: Do you talk about him in your new book — and, if so, where does this discussion come in and what aspects of his career do you emphasize?

SK: My new book only briefly discusses Mo Yan because it spans 3,000 years of Chinese literature in just 137 small-format pages. But I do mention Mo Yan to illustrate how post-Mao writers exhume traumatic memories of the Cultural Revolution, by depicting historical periods before 1949. My example is Mo Yan’s magisterial Red Sorghum, a novel made up of five overlapping novellas in which the narrator imagines his grandparents’ experiences during the Japanese invasion of their village.

I treat Mo Yan’s work at more length in my earlier book, The Heart of Time. His works are among the most memorable of contemporary world fiction because they depict characters that assume real choices in deciding their lives, even as they succumb to powerful forces of instinct, sexuality, and history. One of Mo Yan’s most important themes is whether responsibility for evil lies within individuals or in forces beyond their control, such as fate, lust, or history, forces that can be destructive, but also potentially liberating.

JW: When serious speculation about his potential to win the prize started, jokes began to fly around the Chinese internet. I saw one reference to and translation of at the invaluable China Digital Times mentioned that there have been previous Chinese winners of the prize, but one of them couldn't "get in" and the other couldn't "get out," a reference to literature prize winner Gao Xingjian, who is banned from returning to his homeland, and the 2010 peace prize winner Liu Xiaobo, who is serving a long prison term for his role in drafting "Charter 08," a protest document. A tweet I saw within hours of the news breaking was in Q & A form, asking what one had to do to win a Nobel Prize in China, with the answer being that one had to "shut up," which could be interpreted either as saying one needed to stay quiet about taboo subjects or could have been a play on the meaning of “Mo Yan” (a nom de plume), which means “say nothing.” Is it fair to imply, as some of these jokes do, that Mo Yan is a cautious writer in political terms?

SK: Mo Yan is a brave and unflinching writer. His novels portray graphic violence, rape, even a butcher skinning a prisoner alive, as well as the corruption of officials enforcing the one-child policy. He chronicles many of the horrors of twentieth-century Chinese history, and in my interpretation that includes Mao’s Cultural Revolution. But rather than depict the Cultural Revolution directly, he sets many of his works during World War II when the Japanese brutally invaded China. This historical setting adroitly sidesteps the Party’s sensitivities, and thus flies underneath the censors’ radar. But astute readers may perceive a subtext grappling with the horrors that Chinese citizens inflicted on one another during Mao’s cultural revolution.

JW: Do you have a favorite Mo Yan short story or novel?

SK: The Garlic Ballads (1988) and Frog (2009) are in my view his most accomplished novels, and Shifu, You’ll Do Anything for a Laugh (1999) is full of stories unbeatable for their heartbreaking humor, as many will agree who’ve seen Zhang Yimou’s film adaptation Happy Times (2000). But the work I love most is a 1985 short story, “White Dog and the Swing.” The story describes the narrator’s guilt over his role in an accident that disfigured a childhood friend and changed the course of her life. When he returns years later, the now married mother of disabled triplets pleads with him to conceive a child with her, and the story ends as he faces the momentous decision. The story’s power lies in the conflict between the narrator’s great empathy and his ambivalence about cuckolding her husband to conceive a child with her. (Huo Jianqi made the story into a movie named after the woman, Nuan, in 2003.)

JW: In a piece that Louisa Lim and I did for the New York Times Sunday Book Reviewlast June, we referred to a "gray zone" in which some Chinese writers operate, a space where they can avoid being censored while also saying things that go against the grain of official dictates. You've written a lot about one such "gray zone" writer, Yu Hua. Would you characterize Mo Yan as someone who often, occasionally, or almost never makes use of the "gray zone"?

SK: Mo Yan is usually writing in the grey zone. The works situated during World War II may safely evade criticism of the current regime, but his works on the post-Mao period walk a fine line. In The Garlic Ballads (1988), for example, Mo chronicles a garlic glut that leads to a riot of small-scale farmers against corrupt officials. The stench of rotting garlic infuses the novel, a novel that was initially banned in China. But it was later released, and many readers today may recall its prescient images of warehouses full of rotting garlic as warehouses in China now fill up with overproduced toys and other unsold products.

JW: If readers unfamiliar with Chinese literature want to know more about Mo Yan or about China and Nobel prizes, what book should they order or check out from the library and start reading — other than your own, of course?

SK: If you want to know why I love Chinese fiction, read Chinese fiction. If you want to know why I love Mo Yan, just read anything by Mo Yan. His works seethe with a life force, and his grappling with human aggression transcends national borders. His works shed light on the dark depths of our psyches, a darkness on which China has no monopoly. And under the duress of that darkness, in a world of extreme greed and corruption, his characters also vindicate the human spirit through their passion for life and their abiding devotion to one another. The life force powers destruction, but it also powers what the narrator of Red Sorghum calls “the iron law of love

More Los Angeles Review of Books

-

Jeffrey Wasserstrom interviews Jonathan Campbell

Punk and protest in China and Russia

Shares