I lost my wife in a glass elevator at the Hilton in Frankfurt, Germany. Never mind that I hadn’t exchanged my wedding vows with Marina yet, or tried on the ring that she had engraved with the prophetically impersonal message YOU ARE LOVED. Never mind that Marina wasn’t in the elevator with me or even in the same country when I pressed the button to my floor and felt the car start to rise into the upper reaches of the hotel atrium — that it wasn’t her face looking up at me for a first and long-awaited kiss, her waist trembling in my hands, her handbag sliding off her arm and landing on my foot. It wasn’t Marina who touched my face as if to make sure that I was real and said, “Ti amo, Ben. Ti amo,” and who would spend the night with me in the half-light of a high-rise in the middle of the city, in an airless double room on hotel sheets that felt all wrong against the skin. What was I doing there? It’s not as simple as a fling in a foreign country that I thought I could get away with, though it did cross my mind that I would never have to tell another soul about the elevator ride.

It started with a book. I’d spent the last three years sweating out a novel that never found its voice and filled me with dread up until the day I wrote the final page. I had dreamed it up in a flush of confidence that came from having the kind of career I had always wanted by the age of thirty: my first novel had been a modest hit and there were still foreign editions coming out and a film adaptation in the works at a Hollywood studio; my second book had fulfilled the promise of the first and brought me into the fold of the most storied literary publishing house in the city; I was starting to publish regular book reviews in the papers that mattered and I often got cornered at sweaty parties in identical Brooklyn floor-throughs to discuss the finer points of Philip Roth or the merits of McSweeney’s. I had arrived. At least, it felt like I was arriving. I knew what it was like to be envied by other writers who thought I had it made and to have strangers look up from their novel on the subway—my novel—and stare for a little too long while they tried to place me.

Marina was part of it. I had read her before we ever met: she had published a review of a novel by a bad boy British author in the Nation that had made my heart race with its unexpected disclosures and the fearless energy of its arguments. It felt like it was a love letter meant for me. I gripped the Nation so tightly while I read her review in my apartment that my sweat left fingerprint sized stains on the newsprint. I called Marina a few days later out of the blue at the arts and culture magazine in Soho where she was working, and when I stuttered through an introduction she stopped me and said, “I know who you are! Geez um. Are you calling to make me all nervous?” We arranged to meet at a party later that week thrown by another magazine, and when I walked in and saw her waiting in an empty row of chairs after the reading, I thought, Please let that be Marina. It was Marina. I didn’t have to worry. I sat down in the folding chair next to her and we grinned at each other for a long time without saying a word. The sum of her smile and her hazel eyes and her hair pinned up like a siren’s in a film by Matthew Barney was heady. There was a cocktail party going on behind us, filled with friends and smart young editors on the climb, swirling wine in plastic cups and staring right through the huddling writers who orbited them while pretending not to, but neither of us cared. We sat there grinning at each other instead.

“Hi,” she said, extending her hand for me to shake. She said her name.

I said mine. That was it.

I hadn’t finished my second novel yet, but I was close. I was riding the wave of good fortune in book publishing that only comes, I now know, when you have yet to lose a dime for anyone.

I was prone to bouts of romantic longing, and the city only made them worse. At lunchtime I went up to Union Square, bought a sandwich from a deli, and sat in the park to have lunch in the shadow of 19 Union Square West. The building was nothing special; it was an office tower of a certain vintage, what Henry James would have called a “skyscraper” when it had first been built, but now it looked dwarfed and crowded in by the newer city growing up around it. The stone exterior was drab and soot streaked, the exact color (if it is a color) of a wet newspaper. Somewhere in that building, though, high above the square—or so I imagined—in a book lined suite of offices smelling of old pipe tobacco and secret stores of whiskey, Farrar, Straus and Giroux was busy making books.

I knew a little about publishing, but not much. I had an agent whom I talked to on the phone about the short stories that she was submitting for me, so far without a lot of success, and I had spent two years in Iowa when I was much too young to be in graduate school sitting in workshops led by writers I’d admired on the page before I considered that they might be real people who used urinals and didn’t know how to drive a manual, and I had watched visiting luminaries glide in and out of town on the drafts of their reputations. But still, no matter how many writers I saw sweating through their shirts at the podium or droning on for so long that people started muttering in their seats and gasping, “Oh, come on!” I still had trouble picturing myself in their place. I haunted bookstores whenever I could, gravitating to the new fiction shelf to check out the freshly minted authors and running my fingers over the gently curving spines in neat rows, pulling out the first novels that looked promising and opening them up to the creamy white title page, pausing there before I turned to the copyright and Library of Congress catalog information and scanned them for any clues that might be encoded there, a password that would gain me entry at the gates.

I kept a list in my head of the publishing houses that I wanted to work with the most. Farrar, Straus and Giroux was at the top. It was not just a publisher in my eyes; it was more like the Promised Land. Their books had a shabby, almost European elegance to them, like they knew they belonged on the bookstore shelf—if not in the window, where I often saw them sunning on their backs—and they didn’t have to work too hard to get your attention. The authors won awards and prix and fellowships and medals; they looked haunted in their photos on the jacket, deadly serious about “the craft,” as if they started each day by reading Faulkner’s Nobel Prize address about the human heart in conflict with itself and spent the rest of their time laboring to keep literature alive for the ages.

We don’t publish books, FSG’s motto went, we publish authors. I liked the way that sounded. It had been passed along to me on a fire escape somewhere in Queens by a poet who had been inside the offices once to meet an assistant he had asked on a lunch date. “National Book Awards?” he’d said with a knowingness that filled me with awe. “They paper the fucking place. It’s like a shrine in there. You whisper.” I fell silent in the middle of the party and let it all sink in. We don’t publish books, we publish authors. I thought I knew what it meant. Or did I? I clung to this koan with the fervor of an aspirant who is waiting to be chosen, writing late into the night and in the morning before I went to work in self-inflicted solitude in order to become what I wasn’t yet: an author.

I wondered—as I sat on the benches in Union Square, my lunch spread out in my lap on white deli paper, the park’s jumpy squirrels foraging for leftovers at my feet, and homeless men wheeling past with mountains of empties lashed down to their shopping carts, what kind of mysterious rite I had to pass through or conversion I would have to undergo before I could get up from the bench and leave the park and cross through traffic to 19 Union Square West and sign in with the bored security guard at his desk, letting it slip without looking up from his black binder, “FSG. I’m an author.”

Would it be anything like the Latvian solstice festival I had been to once in high school with my best friend, Michael, when I had stood in a clearing in the woods in New Hampshire and watched seventeen-year-olds vault over a ten-foot bonfire with their skin glowing and cigarettes still dangling on their lower lips as they flipped untouched through rising sparks and landed on the other side? Or would it be simpler and more sudden, like the message I had listened to on a pay phone outside a ferry station in Maine telling me that I had won the fiction contest at a men’s magazine and they were publishing my short story in their next issue? I had celebrated with a pint of Ben & Jerry’s that I ate in the shadow of a Dumpster while I looked out at the lobster boats slicing in and out of Bass Harbor at high tide, then I had climbed in my family’s outboard and sped back across the channel as fast as 35 horsepower could carry me to the island where we had our summer house, grinning into the salt spray while the boat pounded over swells and not caring that I was getting soaked through and shivering myself blue in the sun and the wind.

It happened on a train. Marina and I had caught an afternoon Metro-liner from New York to Union Station in Washington, D.C., at the same time that the bidding for my second novel was coming to a close. I didn’t have a cell phone yet. Not everyone did then. I was still a few years away from the first phantom vibrations inside my pockets, the Pavlovian twitch when someone in the restaurant has the same ring tone. Marina and I were still too new to have raised the topic of living together, but I had started to spend most nights of the week at her apartment on Degraw Street in Carroll Gardens—all it took was one of the ironic “intifada” parties that the hipster Israelis in my building used to throw a floor below me before she had declared my place in Williamsburg unlivable. “Wow,” she said to me the next morning, once we’d finally woken up with a debauched feeling that we hadn’t earned, “I forgot what it’s like to sleep over in the cool kids’ dorm.”

The trip to D.C. was our first as a couple. I hadn’t planned it to coincide with the final round of bidding on my novel, but I was aware, as the train lurched out of Penn Station and broke into the light, that the excitement of closing a book deal while we headed down the Eastern Seaboard on Amtrak could only help my cause. One problem: I would need to use her cell phone. I had listened to it chirrup for attention from the depths of her handbag, and I had watched her squint at the numbers on the little screen when an incoming call interrupted our night, and I had waited a few paces away on the sidewalk, trying not to feel jealous, while she threw herself into a conversation with someone else right in front of me, but that was the extent of my experience with her Sony handheld. “The Thing,” I called it. As in, “The Thing just rang.” Or, “Do you have to bring the Thing?” Or, if she couldn’t find it anywhere and looked stricken: “Don’t worry, the Thing would never leave you.”

“I just heard it,” I told her early in the trip, somewhere at the mouth of New Jersey. We were sitting in our own four-seat suite on Amtrak, side by side. The call. It was definitely the Thing.

Marina reached into her bag and rooted for the phone. “Hold on,” she said. “I know it’s in here ...”

“Um,” I said. “Can you hurry?”

She knotted her brow in concern. Her arm was missing up to the elbow. “Oh, dear.”

“Please? ”

Marina found the phone in mid-ring, thumbed one of its buttons, and pressed it to my ear. Then she beamed at me. “This is when you talk,” she said. “Unless it’s for me.”

It was my new agent, Leo. He had good news. There were two bidders left in the running, both editors we’d targeted and whom I knew I wanted to work with. One worked at an imprint at Doubleday that published fiction I admired and read on my own; the other bidder was a rising young editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

“Give me a number,” Leo said.

I gave him a number. It wasn’t high—a year’s salary at the magazine where I was working plus enough to take a research trip to Europe with Marina.

“Let me call you back,” he said.

The phone rang again outside of Philadelphia. I was holding it this time. I’d had a hard time concentrating when I tried to read, so I just stared at the Thing and waited.

“What button do I press?” I asked Marina. “‘Button’?” she asked. “Did you say ‘button’?” “What’s wrong with ‘button’?”

“It’s just wrong,” she told me. The phone kept on ringing.

“I need to answer!”

“It’s a phone,” she said, “not an elevator.” She pointed: “There.” I pressed the little green phone and put the Thing to my ear. “Hello?” I said.

It was Leo again.

“We’ve got your number,” he said. “From both.” I could hear one of the other agents in his office talking on the phone behind Leo. He had a second career as a TV actor and his voice was shrill enough to carry through concrete block. The bids had improved from the last call, Leo told me over the other agent’s monologue, and they differed in ways that he would explain.

“FSG met the number?” I said. I wanted to be sure that I’d heard Leo right.

I had. They did.

“Where are you?” Leo asked. “Philadelphia,” I told him.

“Think about it,” he said. “Call me back in Baltimore.” “But I don’t need to think,” I said to Leo. “It’s FSG.”

The monologue behind him kept going on. “Do it anyway,” he said.

I looked at Marina beside me on the train. She was so excited for me that she was trembling. I was an author. I had Marina. I had an advance coming that was big enough to last me a year, maybe twice that long if other sales worked out. It felt like I had everything I’d ever wanted. It felt like I had everything.

There are secrets in publishing that no one ever tells you when you’re young. Most books die at their first printing. That’s the biggest one. Some of the books that die are roughly handled on their way to an unmarked grave at Potter’s Field. Others die alone in shipping boxes and no one ever notices. There are the books that arrive with every promise of making their way, garlanded with quotes or launched with an assault on the air waves—still they die like all the others. I remember when I got my first premonition that my novel might turn out to be the rule and not the exception: that it would be published to a faint chorus of reviews, some good and others mixed, a book party at a Chelsea gallery that would merit a line or two in a weekly industry round-up, a few readings at bookstores and performance spaces around town and a few more in other cities to four rows of chairs in the Cookbooks section of a Barnes & Noble or over the whirring of a blender making frozen coffee drinks on the other side of Diet & Health.

A year had gone by since Marina and I took that Metro-liner to D.C. I had already quit my job. I was writing “full time,” which meant that I looked for paying assignments most of the day and spent the rest of it trying to write. My manuscript had gone through rounds of careful edits and there was no more work to be done. I could only wait. And hope.

I was at a recording studio somewhere in Midtown, where my publisher had booked me for an hour. They needed me to read from the book—just a few pages—for a CD that would be included with the advance reading copies (ARCs) they sent to booksellers. I’d chosen a passage from the novel that I thought would be a knockout. Ethan, my editor, agreed. I had practiced until I had the passage close to memorized and every emphasis and dramatic intonation in the right place. In the studio, I sat ready at the microphone. The pages I would read from were stacked and squared in front of me. The engineer in the sound booth had given me my instructions. The recording light went on. He pointed from behind the soundproof glass. I started reading.

I could hear the nerves in my voice at first, but soon the language took over and the hint of a nervous tremor melted away. At some point while I read, the momentum of the scene building and the words rolling out of my mouth, I looked up from the page to see the engineer’s reaction. He was fighting off a yawn behind the glass. It was a monster. That much I could tell. He rubbed his eyes while he listened on his headset. He sipped from a large deli coffee. He froze in his seat with a stricken look, and then it came. He yawned. It was one silent yawn in a sound booth in Midtown, but it carried on for months. It was contagious. I wrote a book. The world yawned.

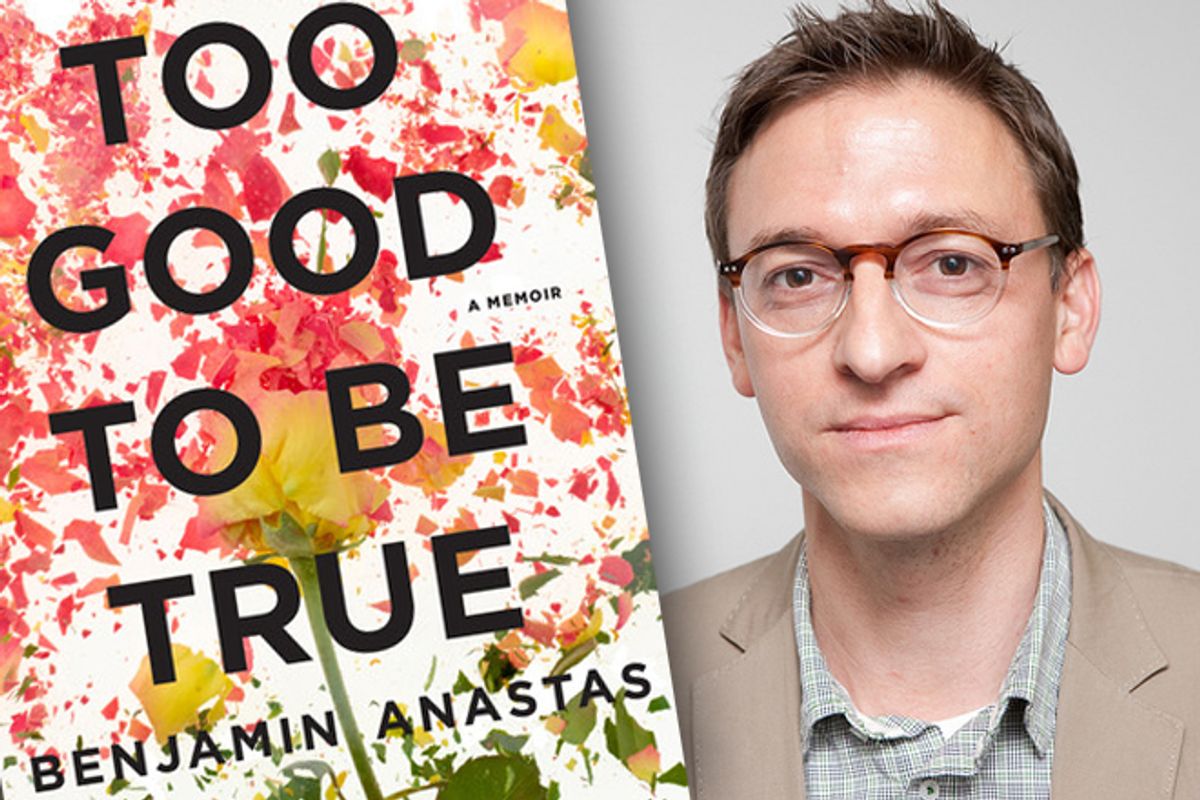

Excerpted from “Too Good to Be True” by Benjamin Anastas. © 2012 by Benjamin Anastas. Published by Amazon Publishing/New Harvest October 2012. All Rights Reserved.

Shares