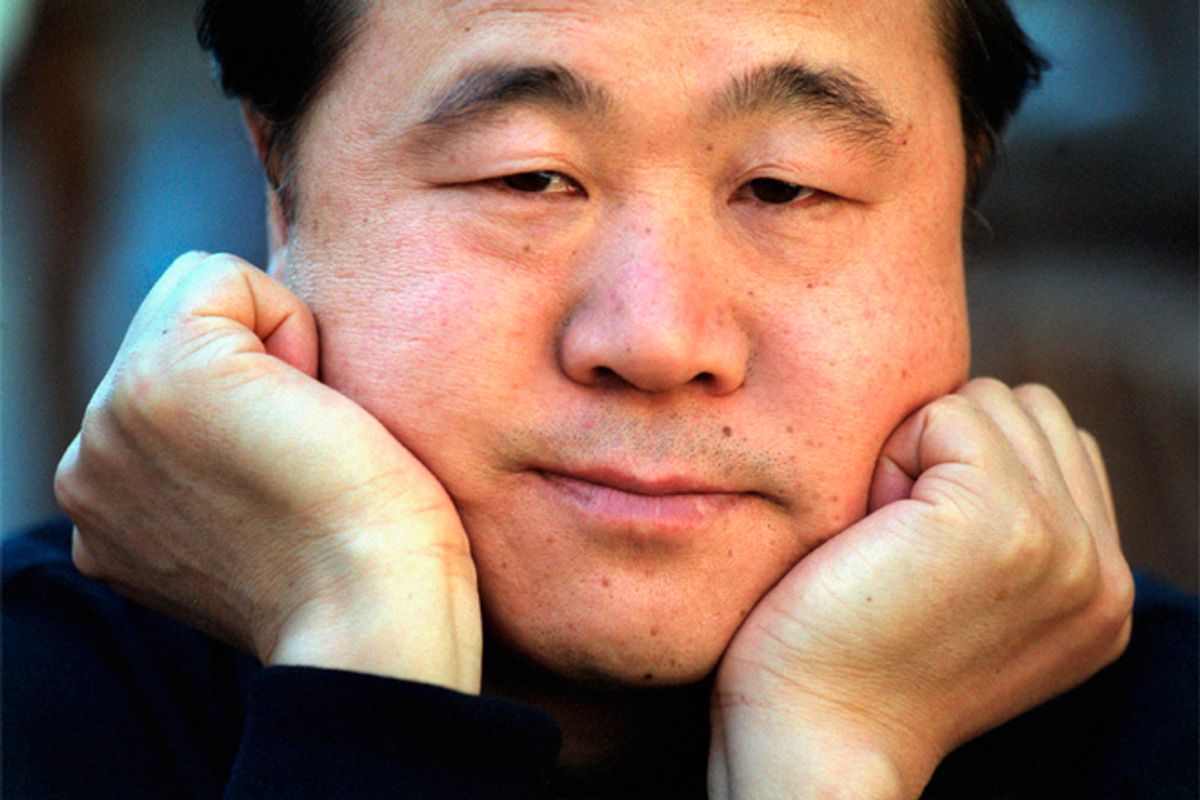

HONG KONG – It didn’t take long for the Chinese government to try to take control of the conversation about Mo Yan.

HONG KONG – It didn’t take long for the Chinese government to try to take control of the conversation about Mo Yan.

Days after the 57-year-old novelist thrilled his country by winning the Nobel Prize for literature, China’s central censorship organ issued a directive to media companies instructing them to strictly police online discussion for anti-party chatter or mentions of two other Chinese-born Nobel winners.

China Digital Times has a translation of the leaked directive:

“To all websites nationwide: In light of Mo Yan winning the Nobel prize for literature, monitoring of microblogs, forums, blogs and similar key points must be strengthened. Be firm in removing all comments which disgrace the party and the government, defame cultural work, mention Nobel laureates Liu Xiaobo and Gao Xingjian and associated harmful material. Without exception, block users from posting for ten days if their writing contains malicious details.”

Liu Xiaobo, a human rights activist and author, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, but he remains in prison in China. Gao Xingjian won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2000 after giving up his Chinese citizenship in 1996.

Official media has also been trying to steer the public toward acceptable lines of thinking about Mo Yan. In the state-run People’s Daily, an editorial urges people to adopt one of “three mentalities” about Mo Yan that “can be considered correct.”

These prescribed perspectives are: seeing his victory as a “blessing” for those in China who “have long had the Nobel Prize complex”; seeing it as a good thing that should not be “over-interpreted”; and rejecting those who criticize his work.

The last order presumably targets those in China who reacted to Mo’s victory with anger. While the overwhelming response was celebratory, a number of reform-minded Chinese knocked Mo Yan for having an apparently cozy relationship with authorities. Mo Yan remains a member of the Communist Party, and the vice chairman of the party-run Writers’ Association. He also contributed to a book of calligraphy in tribute to Mao Zedong.

Liao Yiwu, a celebrated author who was imprisoned for writing about the Tiananmen Square massacre, called the prize “a woeful example of the West's fuzzy morals,” in an interview with Der Spiegel in Germany, where he has lived since fleeing China in 2011.

“Chinese officials feel vindicated in the way they have treated and continue to treat dissidents by such awards. And that is terrible for the people who suffer under them. You have no idea how much the news has angered my friends in China.”

Ran Yunfei, an acerbic writer and pro-democracy activist, called Mo Yan “a man who has no principles” on Twitter and said that the Swedish Academy’s decision makes it “an accomplice to the scoundrel China.”

Cui Weiping, a professor and social critic, wrote on Twitter that, “To those imprisoned writers and those who are being persecuted by censorship as we speak, this is a huge blow,” according to a translation by Seeing Red in China.

Yet this initial backlash has softened somewhat since Mo Yan told a press conference that he hopes imprisoned Nobel laureate Liu Xiabo “can achieve his freedom as soon as possible.”

Still, many observers outside China have continued to ask how Mo Yan can be an independent writer if he is endorsed by the Beijing regime.

A China-based translator, Brendan O’Kane, has offered one of the strongest defenses and explanations of the writer. Far from being a government “stooge,” O'Kane suggests, Mo Yan’s work is inherently—and surrealistically—subversive.

“Mo may not be a ‘dissident’ in the model of Liu Xiaobo or Vaclav Havel, but his work is filled with depictions of the venality, cruelty, and stupidity of power and authority,” he writes. O’Kane cites several of Mo Yan’s novels, including one which depicts a corrupt vice-minister hosting a banquet feast where braised child is served—hardly a flattering portrait of officialdom.

“The fact of the matter is that there are many excellent Chinese authors who are not banned or in jail. They choose to work within the confines of officially acceptable discourse, pushing at the boundaries wherever they can, because the alternatives are banning, or jail, or at best an honorary professorship in Berlin and the lonely irrelevance of the exile.”

By charting a delicate course in China’s mainstream, many argue that Mo Yan has not only avoided conflict with the Communist Party, but also enabled his strange, subversive novels to reach a much larger audience within mainland China. He has already become a national hero: bookstores are running out of stock, one of his novellas has been added to the high-school curriculum, and a rich philanthropist has, bizarrely, offered Mo Yan a free villa in Beijing.

To be an exiled Chinese dissident, however, means being largely unknown and unread at home.

If the Nobel Committee was hoping, by raising his profile and his moral authority, to make Mo Yan an a more outspoken critic of the Chinese government's errors and abuses, it has already succeeded.

As Ai Weiwei said after hearing that Mo Yan said he hoped for the release of Liu Xiabo, "If this sort of courage is the result, I hope more Chinese writers will be given Nobel prizes.

More GlobalPost

-

US election: Kernels of truth in "China bashing"

Both candidates have had harsh words for China, and their tough talk carries huge risks -

US Election: What if China could vote?

"[Obama] is like a dog, running around biting peaceful people for no reason."

Shares