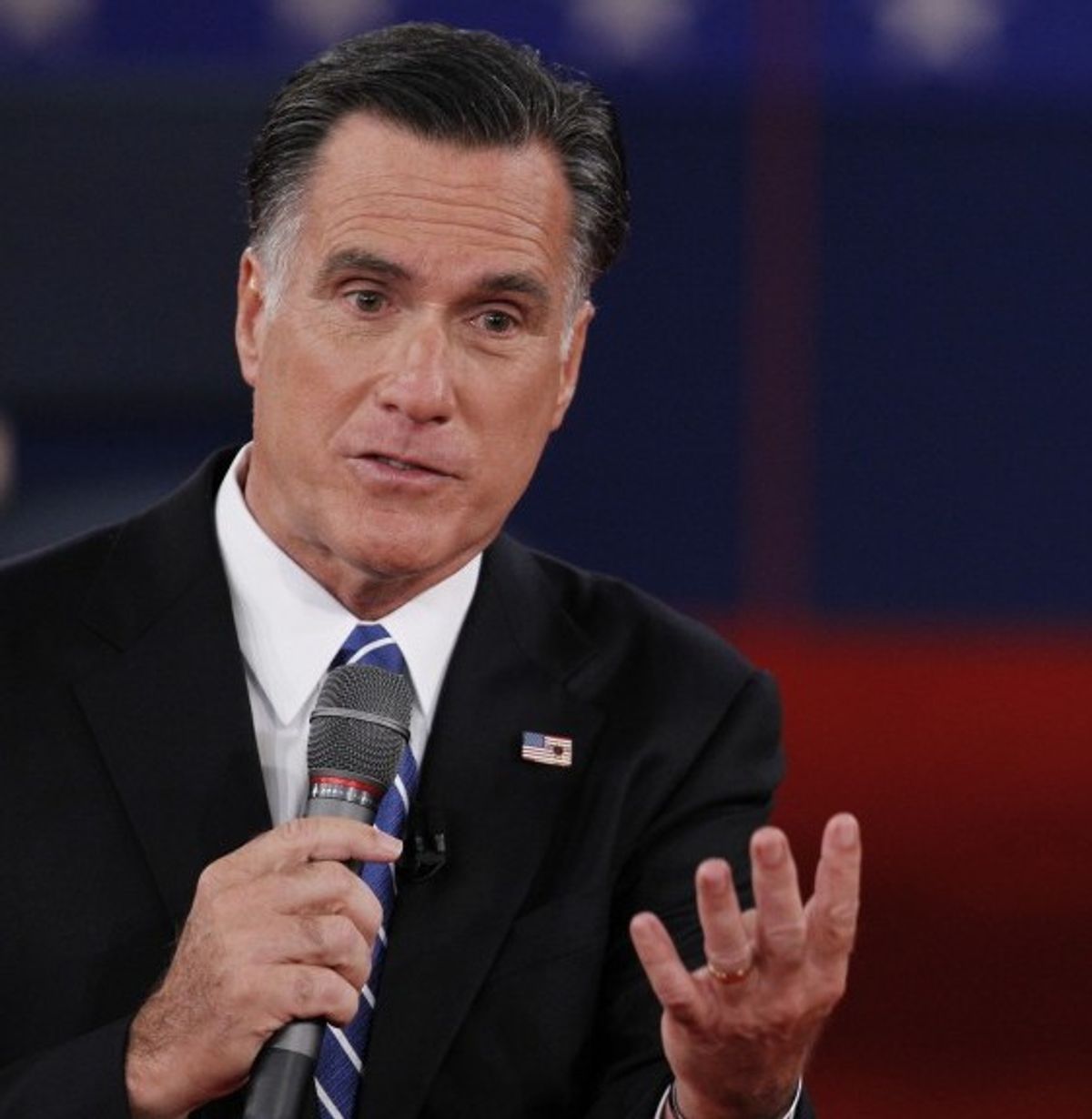

Asked about the gender wage gap last night, Mitt Romney changed the subject. "What we can do to help young women and women of all ages is to have a strong economy, so strong that employers are looking to find good employees and bringing them into their workforce and adapting to a — a flexible work schedule that gives women the opportunities that — that they would otherwise not be able to — to afford," he said. Sensing that he was going to be forced to actually answer the question, Romney added, "I’m going to help women in America get — get good work by getting a stronger economy and by supporting women in the workforce."

There are so many half-formed assumptions and pseudo-promises here that it's hard to know where to start, but let's go to the basic premise: That the wage gap narrows when the economy is strong. That premise, so far as we can see from the data, is wrong.

"In good economic times, bonus payments, overtime hours and merit pay increase," says Ariane Hegewisch, a study director at the Institute for Women's Policy Research. "Women are under-represented in the top echelons," where compensation has soared in good times. "Women are less likely to work overtime," she adds, and "research suggests that merit and performance-related pay still is a key area for gender discrimination." There's also research suggesting that "salary increases related to promotions might differ by gender."

In fact, the recent economic woes actually narrowed the wage gap, because while both men and women suffered, men lost more ground, according to a 2011 IWPR analysis: "Real earnings for both men and women have fallen since 2010, by 0.9 percent for women and 2.1 percent for men." That's likely because male-dominated sectors like construction were hard hit in the recession. Since then, the majority of job gains in the recovery have gone to men, suggesting that (skewed) equilibrium will likely be restored.

Shares