This week brought the second of two exposés that illustrate the twisted state of American labor law, which seemingly permits managers to urge and cajole their employees to donate to and even vote for their favored candidates, and workers to be fired for their political views, even if they express them only outside of work.

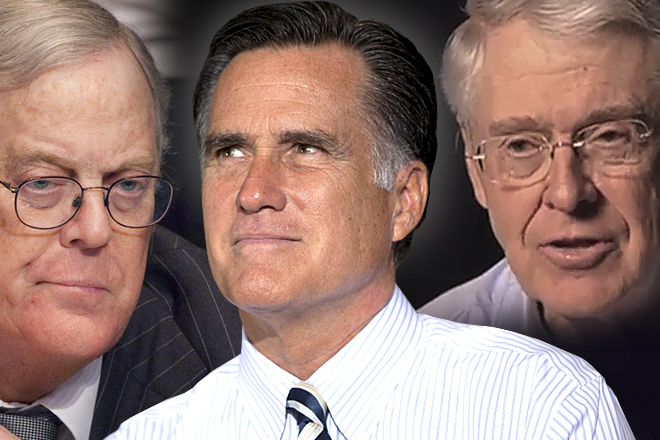

On Sunday, Mike Elk of In These Times revealed a political packet mailed to the 45,000 employees of a Koch Industries’ subsidiary, the Atlanta-based Georgia Pacific. The packet included a list of Koch-endorsed candidates and warned that electing the wrong people could be ruinous to the economy. The company also requires that workers get permission before running for office or joining the boards of nonprofits. One worker told Elk that a supervisor told him he wouldn’t get a promotion because he was “too political.” A local union official told Elk that he was getting calls from Georgia Pacific employees who were afraid they’d be fired for appearing in a photo with a local Democratic state Senate candidate outside their union hall, because the plant where they worked was visible in the backdrop.

You might guess that Mitt Romney would be all in favor of the job-creators telling the hired help how to vote. And you’d be right. As In These Times reported Wednesday evening, in a June conference call Romney told members of the National Federation of Independent Business, “I hope you make it very clear to your employees what you believe is in the best interest of your enterprise and therefore their job and their future in the upcoming elections.”

Elk’s investigation followed similar ones earlier this month by Alec MacGillis of the New Republic. MacGillis tells the story of Robert Murray, an Ohio coal baron and major GOP donor whose employees shell out big-time for his favored candidates. Confirming longtime rumors, MacGillis reported that the coal miners’ generosity isn’t exactly spontaneous. Rather, internal memos and interviews with sources who’ve worked in Murray Energy management revealed that the CEO regularly entreats employees to donate, and aggressively monitors compliance. Workers are urged as soon as they’re hired to sign up for automatic payroll deductions to the company’s PAC. Then Murray sends workers individualized letters suggesting how much, based on their income, they should fork over in additional donations to particular candidates. Workers’ donations can be recorded on a company list or spreadsheet, and managers have been chided when their subordinates underperformed.

Two months before the 2010 elections, Murray wrote a letter warning that if the wrong side won, “the coal industry will be eliminated and so will your job, if you want to remain in this industry.” Murray would no doubt say his words were a prediction. But an employee could easily hear them as a threat.

Koch Industries and Murray Energy have each denied some of the articles’ claims, and confirmed or ignored others. Among Koch’s defenses: They (occasionally) endorse (conservative) Democrats too, and unions also tell their members whom to vote for (never mind that unions can’t fire them for resisting). Both companies say that they’re complying with the law.

The scary part: They could be right. According to Marquette University law professor Paul Secunda, most of the actions Elk and MacGillis reported are perfectly legal. (An attorney for the Campaign Legal Center did tell MacGillis that actually making PAC donations a “condition of employment” would violate the law.)

Why is that? First, thank Citizens United. The Supreme Court’s 2010 decision overturned a key section of federal election law, which had previously restricted how and when employers could make political appeals to rank-and-file employees. That little-noticed aspect of the lightning-rod decision meant open season for any employers itching to tell their employees what to do with their votes or their dollars. It’s not restricted to postal mail – employers are also free to hold mandatory, on-the-clock meetings devoted entirely to lecturing their workers about politics (such “captive audience” meetings have long been a hallmark of anti-union campaigns.)

“Citizens United allows virtually unlimited campaigning by employers in the workplace, under highly coercive circumstances,” says Secunda.

The Supreme Court held that the previous limits on managerial electioneering had violated employers’ First Amendment right to free speech. So do Murray Energy or Georgia Pacific workers have a First Amendment right to talk back without getting canned? Nope.

Because the First Amendment only protects free speech from government interference, private sector employers have nearly free rein to use rewards and punishments to regulate their workers’ speech. That’s not confined to speech that happens at work; federal law also lets employers discriminate against workers for what they say or do on their own time.

Consider Baltimore Ravens linebackers Brendon Ayanbadejo, who spoke out in support of marriage equality, only to have Maryland state delegate Emmet C. Burns urge the Ravens’ owner to shut him up. The pol was wrong on the issue. But, because he was urging that Ayanbadejo’s boss control his speech rather than doing it himself, he was well within the law.

Other cases don’t make headlines. Last year, one of Sen. Richard Lugar’s constituents posted a comment on his Facebook page criticizing local governments for contracting out emergency services to private companies – including her employer, Rural Metro. “The fact that we’re employees of a cheap contract company instead of government employees hurts us,” she wrote. Rural Metro fired her and she turned to the National Labor Relations Board. The board dismissed her case.

Private sector, non-union employees are hired “at will,” which means that, absent evidence of union-busting or racial, gender or religious discrimination, federal law allows them to be fired for almost anything. This principle was upheld in 1990, when a Texas Court of Appeals found that it wasn’t illegal for a woman to be fired for volunteering outside of work with the AIDS Foundation. It briefly made headlines in 2004, when an insulation company fired a worker for refusing to remove a John Kerry bumper sticker from her personal car.

There are a few exceptions. Two states have passed laws against “captive audience” meetings devoted to politics. As of 2010, four states ban firing workers based on their lawful off-duty activities, including politics (in contrast, 29 ban firing workers based on their off-duty smoking).

And certain forms of political activity could be covered by the National Labor Relations Act’s protections for “concerted activities.” Elk reports that some Koch employees are challenging their company’s rules regarding Facebook postings on such grounds. As I reported for Slate in July, the National Labor Relations Board’s jurisprudence is still evolving when it comes to Facebook. The NLRB recently found a car dealership’s social media policy to be written too broadly, because it could discourage legally protected activity. But “concerted activity” only protects collective action aimed at improving work conditions, leaving most political speech or activity far outside its reach.

So federal law lets employers pressure their employees about politics, and even compel their workers to listen. But it doesn’t protect those workers’ right to whisper a political word, even outside of work, without getting fired. Is this a double standard? Brooklyn College political scientist Corey Robin says that’s the wrong way to think about it.

“It actually reflects a single standard …” says Robin, the author of “Fear: The History of a Political Idea”: “It’s British common law adapted for a mass democratic age. Or pseudo-democratic, you might say. Common law traditionally viewed the worker as an extension of the employer’s will.”

Robin argues that pundits who associate “voter suppression” with polling place intimidation, and “corporate power” with super PAC spending, are overlooking companies’ “much more potent means of persuasion” over their own employees: “pure propaganda delivery, by people who have the power to punish you should you not fall in line.”

In the final weeks of the 2012 election, Koch employees and coal workers have gotten a personal taste of that little-discussed power. In the modern U.S. workplace, political debate – like so much else – is a one-sided affair.