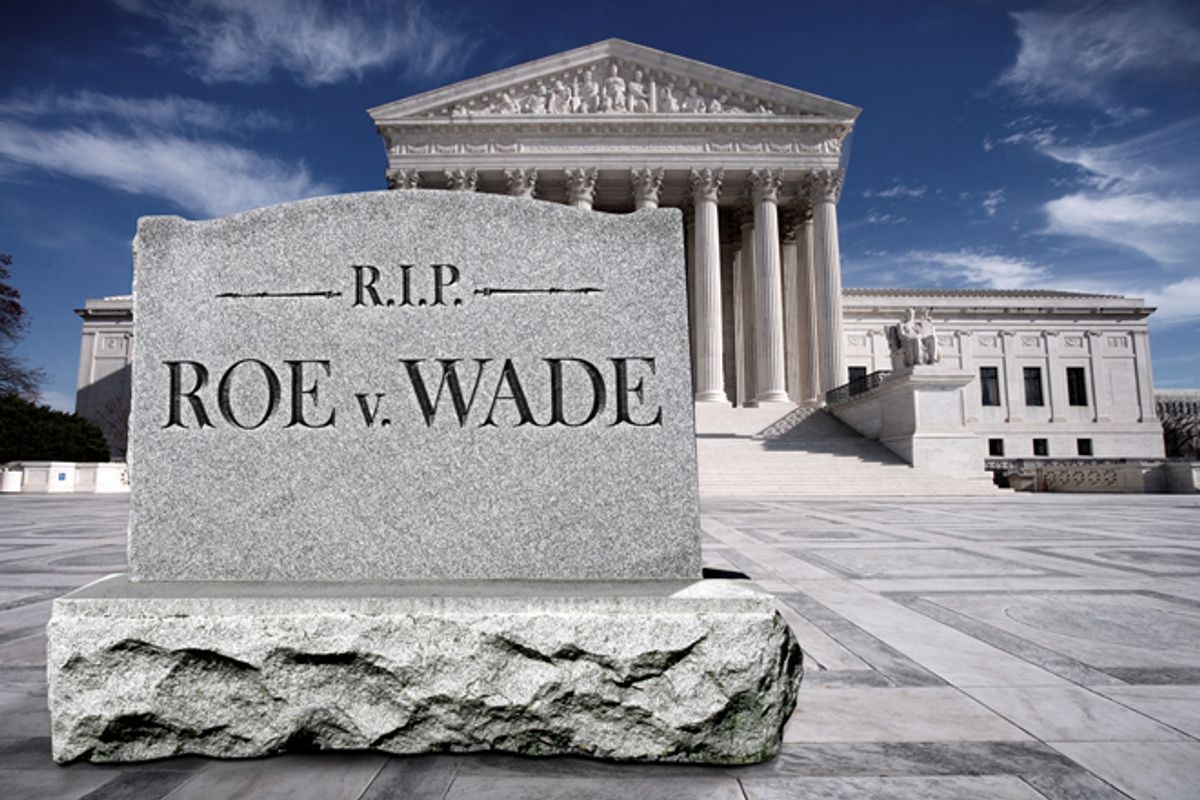

In January, two major events will take place within a day of each other: Roe v. Wade, the Supreme Court decision guaranteeing women the right to an abortion, will turn 40, and a president will be sworn in who will likely determine the 1973 ruling's fate. And if that president is Mitt Romney, anyone who cares about access to a safe and legal abortion should be very worried.

Here's what's important to know about the right's plan for Roe: It will be slow, and it will be indirect -- to avoid a backlash -- but the inexorable goal is to overturn it and ban abortion wherever possible. With an eye toward the court's oldest member, women's rights pioneer Ruth Bader Ginsburg, antiabortion activists would be counting on a President Romney to appoint one or more justices who would upset the fragile 5-4 balance that currently maintains the federal right to an abortion. In the meantime, they've been working hard to lay the groundwork to get a case before the Court that would allow justices to revisit, and possibly overturn, Roe.

"The antiabortion groups are busy trying to fill the pipeline with cases that could present vehicles to revisit the abortion issue, either tangentially or frontally," says Supreme Court expert and author Linda Greenhouse, who has written extensively about Roe. "And the pro-choice groups, on the other hand, are not appealing even adverse rulings, because they don't want such a vehicle to get to the Court" -- even the current, shakily pro-choice court. "Right now," says Greenhouse, "we have a standoff."

Americans are hearing surprisingly little about this standoff on the election trail, except for a few pointed mentions from Vice President Joe Biden. At his debate with social conservative absolutist Paul Ryan, Biden asked rhetorically, "Do you think [Romney's] likely to appoint someone like Scalia or someone else on the court far right that would outlaw abortion? I suspect that would happen." The next day, in Wisconsin, Biden declared, "Roe v. Wade is hanging."

It's true that Romney has repeatedly said that he opposes Roe, including in a National Review Op-Ed in which he called the decision "bad law and bad medicine" and "a misguided ruling that was the result of a small group of activist federal judges legislating from the bench." But much as Roe's enemies would love to "outlaw abortion," that's not directly within their reach -- at least not yet. What they can do is still pretty dire: If Roe is fully reversed and states are free to ban abortion, which Justice Antonin Scalia has frequently called for, abortion could become out of reach for the women of as many as 30 states, according to an analysis of likely state legislation by the Center for Reproductive Rights.

"What you would see in the U.S. is what you see in every country where abortion is illegal, which is that women who have means to travel to New York and California will get them," says CRR president Nancy Northup, "and women who don't have means, will not."

It's not that abortion is universally accessible right now -- far from it. The Supreme Court's 1992 split-the-difference decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey gave states plenty of leeway to limit abortion, short of actually making it illegal. The resulting state laws are a deliberate effort to make abortion as quietly difficult as possible, at the same time as abortion foes are carefully laying as many traps as possible to force pro-choice litigators into court. Those laws have been increasingly innovative, from forcing women to listen to and view ultrasounds, to trumped-up regulations designed to shut down abortion clinics, to bans on the barely existent problem of sex-selective abortion.

Such laws allow antiabortion activists to claim loudly to the American public, which has said repeatedly that it doesn't want abortion to be illegal, that they won't really ban it -- that all they want is "sensible" abortion restrictions. To their own people, they are open about the strategy, as conservative legal strategist James Bopp was in a 2007 memo discouraging his allies from pursuing total abortion bans. "Now is not the time to pass state constitutional amendments or bills banning abortion," he wrote. He argued that such cases could make matters even worse, by triggering a backlash and potentially even strengthening the legal right to abortion: "No amount of stirring rhetoric arguing that the states have a duty to do something to trigger reconsideration of Roe changes the hard fact that such an effort is presently doomed to expensive failure."

After a crushing loss for a "personhood" amendment in conservative Mississippi last year, antiabortion activists have more reason than ever to pursue that incremental strategy. And indeed, personhood amendments, which classify a fertilized egg as a person, aren't on the ballot in a single state this year. The movement's best hope, at least until they have the right Court composition, is to keep flooding the system with an unprecedented wave of antiabortion laws -- something that's been easy enough to do in the past two years with the far-right Republican takeover of the House of Representatives and statehouses across the country -- and wait.

They have reason to be optimistic. The court has already tilted in their favor in just the past few years, with a moderate Republican, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, having been replaced by the more conservative Samuel Alito. The so-called Partial Birth Abortion Bans of the '90s, which vaguely banned a particular later abortion procedure, were a classic success of the incremental strategy. Even nominally pro-choice people were horrified by the graphic imagery involved, and on the face of it, the ban wasn't on abortion itself, it was on a procedure. A Nebraska ban on the procedure was overturned by the Court in 2000, but seven years later, the Court said an identical federal ban was OK, thanks to the presence of Alito.

"They directly reversed the rule from 2000," says Priscilla Smith, a senior fellow at Yale Law School, who argued the 2007 case, Gonzalez v. Carhart. "One decision was, we'll err on the side of the woman's health. The other was, seven years later, we'll err on the side of the state." So much for judicial precedent. At the same time, Justice Anthony Kennedy alarmed pro-choice observers with an opinion rhapsodizing, irrelevantly, about how some women regret having abortions.

We don't know how long it would take for another shift. Though all eyes are on Ginsburg, a two-time cancer survivor, Greenhouse says, "I think predicting retirements is kind of a foolish game and I am far from sure there are going to be any retirements in the next four years." And she points out that in the short term, "under a President Romney, if the Democrats retain concern of the Senate, he will not have the unfettered discretion" to work his will. Still, these days and in many places, they've taken over the party outright. Greenhouse says, "I'll take the Republican platform at its word. I think Romney would be perfectly happy to turn this whole matter over to his base." And the right is playing a long game: Antiabortion activists aren't afraid to lose in court and try again, and again.

What's more, the conservative base is best represented by Romney's own running mate, Paul Ryan, a favorite son of the antiabortion movement who has made it clear that he would like to see abortion banned in just about every circumstance, even warning darkly of the dangers of an exception for the health of a woman.

The Trojan horse that worries pro-choice legal scholars the most are the so-called fetal pain laws, which ban abortion at around 20 weeks, well before viability, on the scientifically spurious, and currently constitutionally irrelevant, basis that a fetus experiences pain at that point. They've passed in seven states, including Indiana, Kansas and Nebraska. Like the Partial Birth Abortion Bans, these laws promise to put focus on rarer, but less politically palatable, later abortions.

After declining to take the antiabortion bait in several states, CRR and the ACLU are challenging a version of the law in Arizona that effectively bans abortion at 18 weeks and has a very narrow health exception. (The 9th Circuit agreed to enjoin the law and will hear the case next month.) The stated intention of the law's defenders is for the Supreme Court to eventually take the case and totally reframe its approach to abortion rights to take into account what happens to the fetus before viability. But pro-choice litigators are betting that the Supreme Court wouldn't hear it. Says Smith, "It would be outrageous if they took it, because there's no conflict in the circuits. It would be a hugely activist move."

For now, all of these battles are being fought below the public radar in lower federal courts, where the ranks of liberal judges are thinner than they might be, thanks to Obama's slowness in making nominations and the determined Republican opposition to those he does nominate. Judicial discretion is key here. The Casey decision held that a state could do anything but impose an "undue burden" on a woman who wants an abortion, but as Northup puts it, "What an undue burden is is very much in the eye of the judge that's hearing the case."

As long as the game of chicken proceeds, abortion opponents are succeeding in chipping away access and stigmatizing abortion without triggering very much urgency from the American public. "The question is," says Greenhouse, "what is the functional meaning of Roe going to be if the serious burdens and obstacles are getting the green light from the federal courts?" Even if antiabortion activists don't get their immediate wish of overturning Roe outright, they've already succeeded in making it mean less than ever.

Shares