A month ago, the eccentric Chicago rapper Lupe Fiasco released "Food & Liquor II: The Great American Rap Album Pt. 1," which shared an all-black cover with, among other things, Spinal Tap’s "Smell the Glove," and banked on a single that attempted to declassify the evils of using the word “bitch.” Songs alluded to Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” and Pete Rock and C.L. Smooth’s “T.R.O.Y. (They Reminisce Over You).” But despite a healthy (and American!) skepticism of the president and the military-industrial complex, most agreed that it was not the great American rap album — it’s too condescending, particularly to women, skillful but muddled, and told more often than showed.

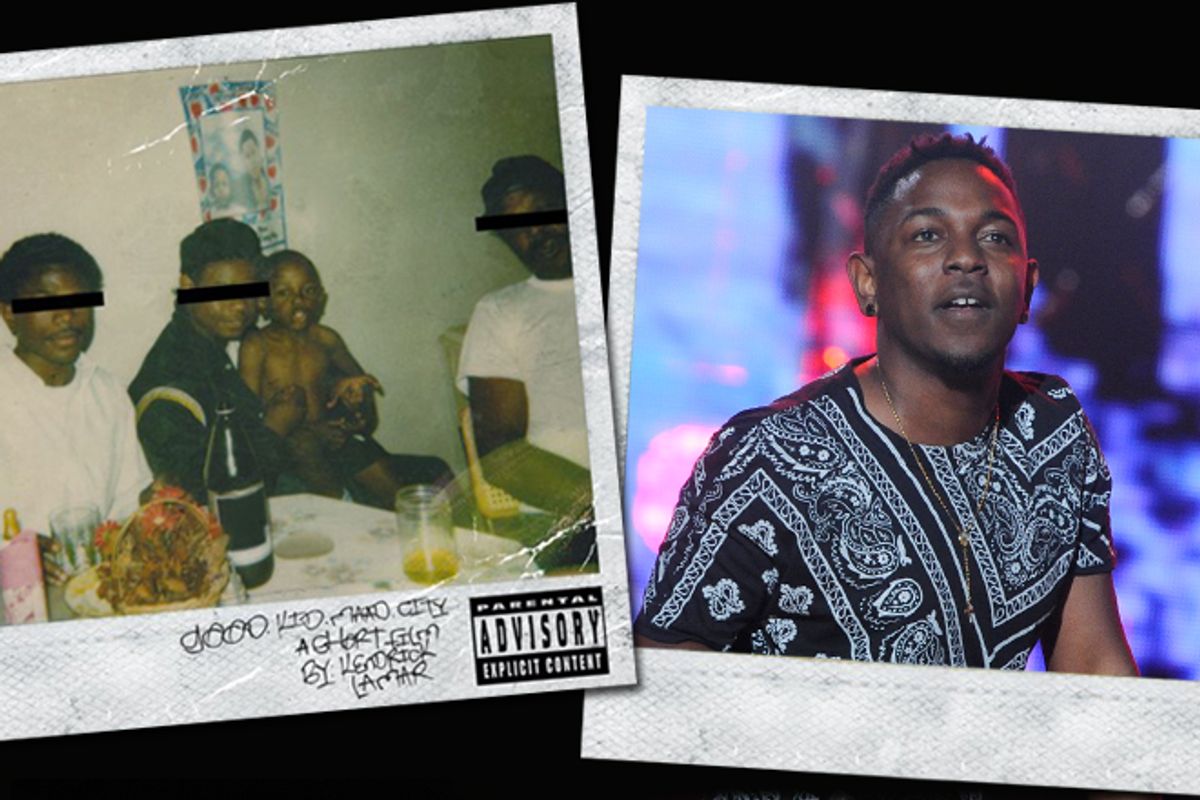

But it was a nice conversation starter. What could the Great American Rap Album possibly look like in 2012? Having watched blogger’s pets like Wale, Curren$y, Big K.R.I.T. and B.o.B fail to complete the respective missions their original cult hero status assigned them as their major-label efforts topped or fell off the charts, few rap fans of late have put stock into the idea that a new “unsigned hype” could still change the charts for the better. With those expectations receded, people became cautiously excited about Kendrick Lamar, a mysteriously calm rapper from Compton — yup, the very same — with a crew called Black Hippy, a Dr. Dre hookup, and a past with some privileged knowledge of gang activity. His major-label debut, "good kid, m.A.A.d. city," out this week, is raking in near-perfect scores from Pitchfork and Rolling Stone among strong word of mouth and pixel that it’s the real Great American Rap Album. Sean Fennessey of Grantland compared it to "The Third Man" and "The Great Gatsby," while the Polaroid family portrait on the album cover features the scrawling “a short film by Kendrick Lamar.”

In one cut, called “Poetic Justice,” a screwed-down voice intones, “Say if you a bad bitch put your hands up high.” Lamar’s very much the opposite of Lupe Fiasco. He has faith in slice-and-dice wordplay — the standout teenage aside “Backseat Freestyle” makes short work of anyone who didn’t take him for a battler — but he lets his characters and their surroundings do the talking, shrinks his personality in the service of the stories. Like a director, he doesn’t get caught on how bad the language is that those characters use. He’s not out to change the lexicon but employ it.

Lamar’s sound, startlingly removed from the lavish orchestrations of Rick Ross and the vacuum-synth-and-Auto-Tune of current crossover champs like Drake, closely brings to mind pre-fame OutKast, Roots and Nas, while his constantly shifting voice most often settles on a thoughtful purr reminiscent of Q-Tip who knows his post-Kanye coughs and inflections. This stuff never went away. But it hasn’t been at the center of the conversation for a long time. New upstarts like Joey Bada$$ and even Odd Future have been credited with resetting rap’s clock and progressing from 1993 or so, "Illmatic" and Mobb Deep and the Wu all over again. But only Kendrick has tracks with Lady Gaga in the vault.

Rap has always strived for the cinema, which is why so many rappers end up in movies, a fiction medium that’s paradoxically meant to capture realness. Even early on, Run-D.M.C. were granted a feature film, just before Prince Paul and De La Soul invented the hip-hop skit. Paul would later go on to realize the first “rap opera,” "A Prince Among Thieves." But with respect to the one-of-a-kind Ghostface Killah, Lamar’s only severe competition as a storyteller right now is a Chicago rapper named David Cohn who goes by the name Serengeti. Cohn’s greatest work is rapping as the vaguely Polish, O’Doul’s-and-Bears-loving suburban husband Kenny Dennis. The trials and tribulations of Kenny have now informed four or five records in the Serengeti discography, which chart out mundane activities unheard of in rap (the wife sending him back to the store to get a “damn bag of ice,” growing a mustache the “size of Mike Ditka’s forehead”). It remains mostly obscure, if breathtaking stuff.

The difference between Kenny’s movie and Kendrick’s is that Kendrick’s has guns. Normally this would be something to grouse over. Instead, Lamar is closing a gap that’s taken hip-hop generations to get respect for: contextualizing violence in a way that doesn’t glorify it. Yes, "good kid" is stamped with a big fat Dr. Dre denouement called “Compton” that ought to bring in a couple curious N.W.A. diehards. But the West Coast décor is there for just that: to attract people to his thoughts, his memories, his reasons and conclusions. A song like “Money Trees” may employ the shoot-and-hustle ethos (“My homeboy just domed a nigga/ I just hope the lord forgive him”) but the recurring emotion on this album is worry. There is never a sense that Kendrick, dexterous as he may be, enjoys some sort of advantage of those he sees victimized.

In fact, most of his scruples are pure accident. The opening “Sherane A.K.A. Master Splinter’s Daughter” spends three verses detailing the summer he gets to know a girl whose “family history of gangbanging did make me skeptical/ But not enough to stop me from getting a nut.” The horny rapper gets jumped the next time he goes to her house, but cuts away because his mom called. She needs the car back, and while he's at it, has he seen dad's dominoes? The robbery tale is called “The Art of Peer Pressure”: “My mama called/ "Hello? What you doin'? “Kicking it”/ I should’ve told her I’m probably ‘bout to catch my first offense with the homies.” It’s telling that Lamar doesn’t find the action where the bullets are, but in the supporting cast, the mother he’s lying to, the woman he’s not sure about.

In keeping with the dusty 40oz-and-baby-bottle album art, the record strives for “period piece,” yet so many of the tropes that fly in and out of its hazy consciousness apply today, especially the line about “living in a world that come with Plan B/ A scapegoat cuz Plan A don’t come free.” A budding superstar aware of the inner-city-as-scapegoat is a big deal even if he gets the credible audience’s attention via lines like “I wish my dick was as big as the Eiffel Tower/ So I could fuck the world for 72 hours” that a more pious artist like Brother Ali lacks.

Unless Eminem’s on-record love for his daughter counts, the only other Dre-affiliated rapper to ever work this angle of deep moralizer inside a confusion of gangs is dead. Kendrick dusts off the Tupac mold with a dexterity usually reserved for fast-talkers from the South, and an empathy for women that would be unheard of in any rap region but especially California. You could call "good kid, m.A.A.d city" a prequel to the disgruntled cartoons N.W.A. portrayed on "Straight Outta Compton," its "Batman Begins." It’s like Lamar is detailing the process of desensitizing himself, which may re-sensitize rap fans in the process. Or maybe it’s a product of a rap generation deepening in the first place, putting “Nuttin’ but a ‘G’ Thang” under the microscope and seeing if those violent fantasies could still scan as a party today, in the wake of the Batman shooter and Trayvon Martin and teen suicide in a nation of towering college debt and staggering unemployment. In that context, Lamar’s tales of “peer pressure” indeed scan sympathetic, as a life people from this desolate people don’t feel they can escape; no kids will be imitating the violence on this record because they have to be smart enough to notice it in the first place, which requires some digging.

"The Third Man" or "The Great Gatsby" it may not be, but "good kid, m.A.A.d. city" is certainly the first rap album in many years to bring grand introspection to the mainstream in a way that's both inside and outside of the violent goings-on, which might be what a spooky guest hook from Pharrell calls “Mass hallucination baby/ Ill education baby” on “Good Kid,” where Lamar’s seemingly the prize in a tug-of-war between gangs (“What am I supposed to do/ When the topic is red or blue”) on his way back from — getting ridiculous now — bible study. Lamar wants us to imagine the age-old Faustian bargain with his family as the angle on one shoulder and “M.A.A.D City” as the devil on the other, in the album’s two-song title centerpiece. He chooses neither and continues down the middle. The next song extols “swimming pools full of liquor” in such a funereal manner that it’s difficult to tell is an endorsement: “All the girls wanna play Baywatch” has never sounded so ominous. It’s that sort of slogan-proof gray area that Lamar wants to take to the masses. Current rap that resonates to the monoculture-at-large is such a sinkhole that he’s actually getting a shot. If more rap like this catches on, the next talented upstart might not even have to rely on the genre’s own violent remembrances to catch on.

Shares