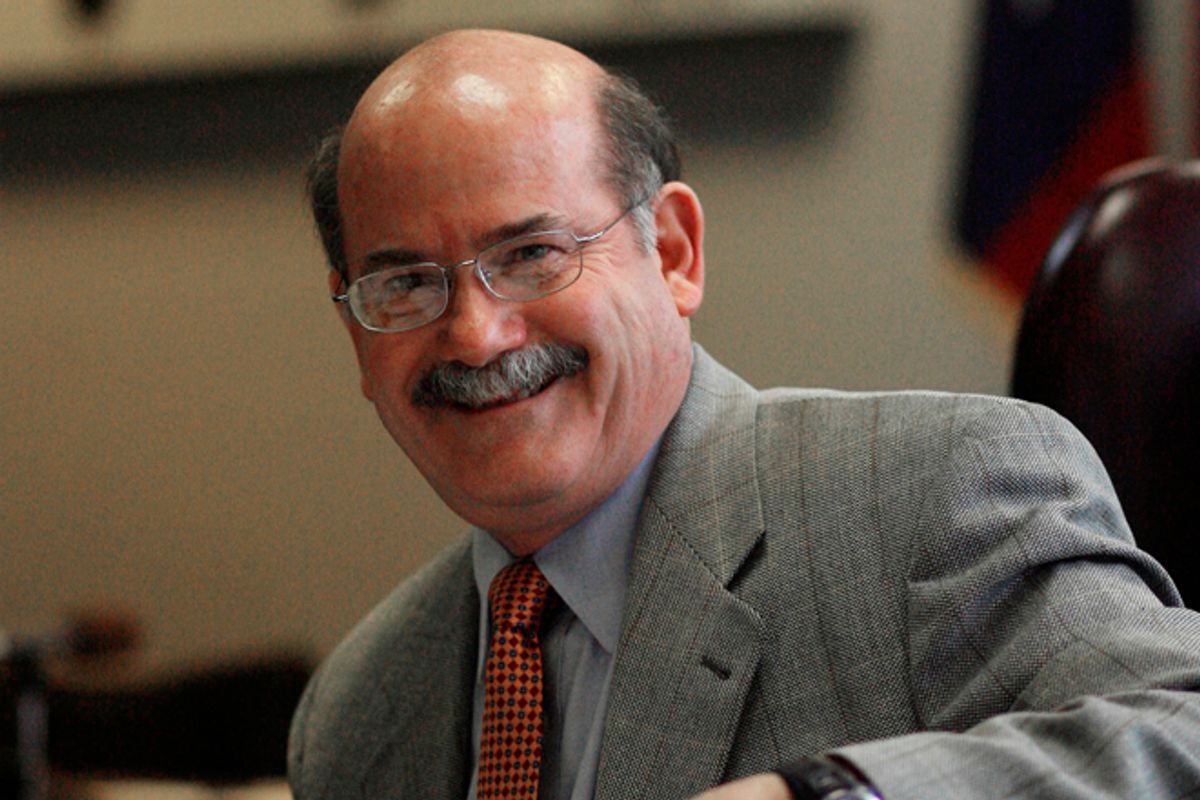

Don McLeroy is a dentist in suburban Texas with the geeky, earnest manner of an American guy who has educated himself, however imperfectly, on a wide variety of topics. With his balding pate and high-waisted, pleated slacks, he makes Ned Flanders from “The Simpsons” look like Mick Jagger, circa 1969. I found myself utterly unable to resist McLeroy, who is likable and 100 percent sincere. He’d be a great neighbor, in large ways and small; the kind of guy who’d pull over on a busy highway to help a stranded motorist, while everybody else zoomed past. But as we see in the documentary “The Revisionaries,” it’d be a mistake to consider him harmless just because he’s a nice fellow.

As a Tea Party zealot, fundamentalist Christian, young-Earth Creationist and, for a while, chairman of the Texas State Board of Education, McLeroy became nationally notorious for his efforts to undermine scientific education and sneak covert religion into textbooks. One of the great things about Scott Thurman’s film — a low-budget but thoroughly watchable documentary, largely funded on Kickstarter – is that it helped me see the world from McLeroy’s point of view, which I might previously have considered impossible. He feels almost painfully oppressed by arrogant experts with fancy university degrees who insist on a difference between scientific evidence and faith-based personal opinion, and he genuinely believes that the half-baked, cherry-picked “weaknesses” in evolutionary theory expose the ideological underpinnings of modern science.

But if McLeroy is the most famous figure, and oddly the most compelling, in the Texas textbook battle of recent years, “The Revisionaries” makes clear that others were probably more powerful and influential. National media drifted away from the half-comic, half-tedious circus of the Austin school board meetings after the partially successful right-wing attempt to wiggle discussion of “intelligent design” into science textbooks that addressed evolution. But Thurman and his fellow filmmakers stuck around for a battle over social-science textbooks that was arguably worse, since opinions and analyses in that field can’t be subjected to the same scientific rigor. Culture-war amendments were added fast and furious to the academic standards in that area: removing references to the slave trade from the texts and praising leaders of the Confederacy; substituting “country music” for “hip-hop” in a discussion of pop culture; adding, preposterously, religious figures like Thomas Aquinas and John Calvin as inspirations for the American Revolution, while deleting the word “Enlightenment.” (One board member even suggested that every reference to Barack Obama should include his middle name.)

Many of those were the work of Cynthia Dunbar, a board member who is much smoother, subtler and smarter than McLeroy – and enormously more dangerous. Dunbar is a highly articulate lawyer who teaches at Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University in Virginia, and who was evidently groomed for her position on the Texas board by political activists on the Christian right. She cooperates readily with Thurman’s film and appears to have nothing to hide, but neither in talking-head interviews nor in board sessions does she ever offer the least insight into her personality, offering bland generalities about “community service” as she doggedly pursues a hard-right agenda. McLeroy is honest to a fault, haranguing his dental patients and Sunday-school students about Noah’s ark – yes, he got the dinosaurs on there somehow – and apologizing regretfully for his most inflammatory statements. Nothing, on the other hand, ever penetrates Dunbar’s Teflon surface; I had to consult Wikipedia to learn that she has described public education as unconstitutional and a “subtly deceptive tool of perversion.” (She served one term on the board and did not run for reelection; one gets the feeling bigger things are contemplated.)

McLeroy, for example, is almost distressingly eager to pursue an awkward friendship with Ron Wetherington, an anthropology professor at Southern Methodist University who leads what might be called the secular-humanist faction in the textbook battle. Wetherington is himself a character sent by Central Casting, a goatee-wearing academic who lives surrounded by books in a spectacular house and moves through the world with a distinctive air of pomposity. It’s entertaining to hear him describe the Texas board’s toxic combination of “arrogance and ignorance,” but from a political point of view someone else (anyone else!) might have been preferable. You can tell it’s acutely painful for him to suffer fools gladly, but the scene when McLeroy and Wetherington share a cordial dinner is actually a moment of genuine human decency amid the bleak and blasted political-cultural landscape depicted by this film. (I suppose Cynthia Dunbar would eat dinner with Satan, Lenin’s corpse and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad if she thought it would pay off politically, but she’d wear a plastic smile the whole time and ask them questions about their kids without listening to the answers.)

If Ron Wetherington makes a kind of imperfect hero in “The Revisionaries,” Thurman paints a less distinctive portrait of Kathy Miller, head of the Texas Freedom Network, a grass-roots activist organization that has battled against the Christian right, especially on the schoolbook issue, for many years. Miller serves almost as a narrator or Greek chorus in the film, offering commentary on other figures like McLeroy, Dunbar and the legendary Texas couple Mel and Norma Gabler, who pioneered the nationwide evangelical attack on “ideas, situation ethics [sic], values [and] anti-God humanism” within public education. (McLeroy is indignant that Miller's group has taken a name that sounds like it should belong to a right-wing, Bible-thumping organization.)

On one hand, “The Revisionaries” is clearly meant to support Miller’s argument, which is that liberals and progressives need to focus harder on fighting at the granular level of school-board elections and other lower-level political bodies that actually set policy, as opposed to electing the lesser of two evils every four years. That’s true and all, but I can’t help feeling that on a larger scale people like McLeroy and the vastly more sinister Dunbar are trying to fight back the tide of demographic and social change. Non-Hispanic whites are already a minority in Texas – and a rapidly shrinking minority among those under 18. What’s keeping the state reliably red are the lower rates of citizenship and voting among minorities, both of which will normalize over time. Yes, the right can edit Cesar Chavez and Rosa Parks out of the textbooks, and concoct tortured phrases meant to undercut Darwinism. But how long can that extend their hegemony? I’m left with the vision of Don McLeroy wandering around a soccer field with a handful of Sunday school kids, pacing off 300 cubits by 50 cubits and explaining how Noah got those caribou and beavers and scorpions and T-rexes in there. The lower of the three decks, he tells the kids, was for all the poop. I always wondered about that!

“The Revisionaries” opens this week at the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center in New York, the Laemmle Playhouse 7 in Los Angeles and the Violet Crown Cinema in Austin, Texas, with more cities and home-video release to follow.

Shares