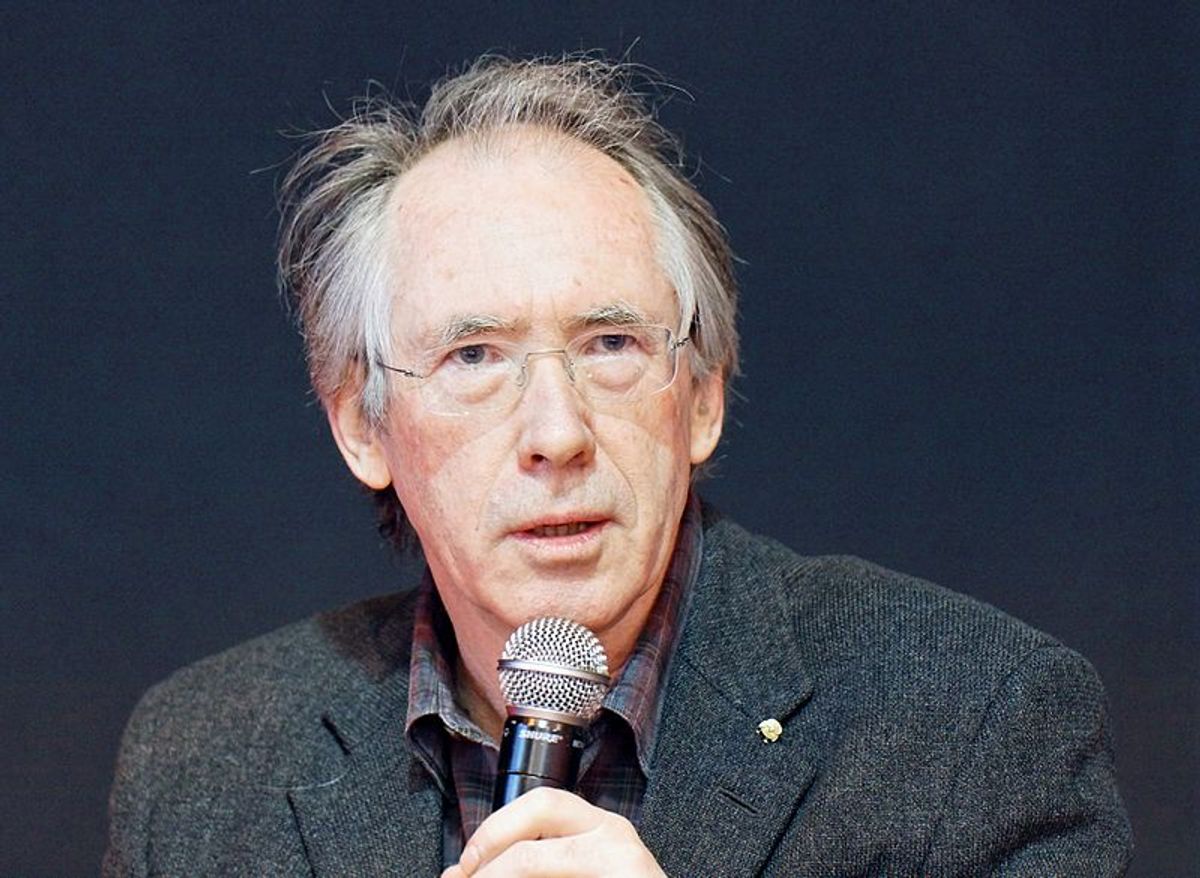

EVER SINCE HE EVOLVED out of producing what he describes as ‘staring-at-the-wall’ fiction — those slender stories such as The Cement Garden and The Comfort of Strangers set in no tangible time or place —Ian McEwan has become England’s premier documentarian, the chief recorder of her near past in novelistic form.

Moving seamlessly between time periods, from the Second World War to the liberation of Iraq, McEwan’s attention is drawn not towards the deeds of great men that flavor the works of say Hilary Mantel or Robert Harris. McEwan, while oftentimes anchoring his works in the past, is by no means a historical novelist. Rather, his novels attempt to reflect the Zeitgeist, how the ever-changing political, social, and cultural climate impacted or impacts the lives of ordinary or at times extraordinary people.

Amsterdam — a novel largely underrated as a consequence of it being overrated by the Booker Prize committee — was set and published in the 1990s and is above all else a manifestation of both pre-millennial and post-Soviet angst. Clive Linley’s inability to create an original, harmonious, and uplifting conclusion to his Millennial Symphony is a sign of the politically and culturally directionless state of the nation at the fag-end of the Major government, and the fear that the 1990s was to be an uninventive, imitative decade. “They say you’ve ripped off Beethoven something rotten,” music critic Paul Lanark says to Linley at a reception for his composition. “I suppose you’d call it sampling.”

Through Linley and McEwan’s other central character, the newspaper editor Vernon Halliday, McEwan explores in addition the individualisation of English society during that period — a consequence of 18 years of Thatcherite administration. Both Halliday and Linley make decisions related to their work which they believe may secure them and aid their advancement, yet impact negatively upon the lives of others. As Linley rambles across the Lake District, he chooses to ignore a violent disturbance, concerned more with the melody forming in his mind.

Remarkably astute too is McEwan’s post 9/11 novel, Saturday, which captures not only the fear and anxiety that was all too palpable at the time and continues to mutate the ways in which we interact with the world, but also the sense of naked vulnerability that enveloped residents of London, New York, and metropolises elsewhere, born of a knowledge that terrorists had struck once and could quite easily do so again:

London, his small part of it, lies wide open, impossible to defend, waiting for its bomb, like a hundred other cities. Rush hour will be a convenient time. [...] The authorities agree, an attack’s inevitable. He lives in different times — because the newspapers say so doesn’t mean it isn’t true.

With the possible exception of Atonement — where class resentment is a latent cause of Briony’s hostility towards Robbie, and the total effect of war forces her to cross boundaries, becoming a trainee nurse in a London hospital for the wounded — the England of McEwan’s novels does not give life to all classes. His characters usually enjoy comfortable lifestyles, as members of the professional and artistic classes inhabiting worlds of plush abodes and boozy suppers. The beginning of Enduring Love has Joe, a science journalist, and Clarissa, a college professor, sprawled out under an oak tree in the Chilterns, enjoying a bottle of 1987 Daumas Gassac. Amsterdam’s friends and rivals Linley and Halliday are, if the subtext is ignored, burdened by what we might now term first-world problems, stultified creativity and ethical dilemmas.

It is an England in which McEwan is clearly most comfortable and in Sweet Tooth — his latest endeavor, grounded in the cultural Cold War of the early 1970s — we find two characters who for a time relish an innocent, embryonic version of this middle class idyll even as the rest of the country is descending into chaos and catastrophe. Serena Frome and Tom Haley drink copious amounts of Chablis, “though neither of us knew a thing about wine.” They make a point of going to Wheeler’s fish restaurant in The Lanes — a rickety, bohemian quarter in the centre of Brighton — and ordering “two glasses of champagne and a dozen oysters.” “I’m not sure we really liked them,” Serena explains, “but we liked the idea of them, the oval arrangement of barnacled ancient life among the parsley and halved lemons”.

Essential to McEwan’s talent is this ability to capture the texture of everyday life without it appearing as though such observations have been wedged into the narrative. His novel of the 1960s, On Chesil Beach, details a honeymoon experience before the coming of the sexual revolution and the grand opening of postwar England to foreign influences. The manner in which McEwan details their first meal as man and wife perfectly captures the era’s pathetic culinary shabbiness:

The formal meal began, as so many did then, with a slice of melon decorated by a single glazed cherry. Out in the corridor, in silver dishes on candle-heated plate warmers, waited slices of long-ago roasted beef in a thickened gravy, soft boiled vegetables, and potatoes of a bluish hue. The wine was from France, though no particular region was mentioned on the label, which was embellished with a solitary, darting swallow. It would not have crossed Edward’s mind to order a red.

Whereas On Chesil Beach takes McEwan’s doomed newlyweds Edward and Florence to the “darkening shingle” of England’s Jurassic Coast, Sweet Tooth returns the author to the urban setting, particularly the drab, filthy London of the Heath and Wilson governments. Serena rents a room in a house near the Camden Road which had “not yet escaped its inheritance of Victorian gloom.” The property is heated by an electric fire and the floors “covered in ancient brown lino in the corridors and kitchen, and elsewhere with floral carpeting that was sticky underfoot.” Beginning life “as a clerical officer of the lowest grade” in an austere office block operated by MI5, Serena notes how in the chill induced by the fuel shortage, agents and administrators “worked in our overcoats and finger gloves,” adding “we were issued with squares of felt to put under our feet against the cold coming up through the floor.”

Appropriate to the bleak and perhaps claustrophobic nature of the period when flight from England was made difficult due to economic uncertainty, Serena’s life is largely confined to two urban settings: dank, grimy London where the garbage piles up in the streets; and Brighton, which acts as a sort of escape for Serena, a seaside town of air, light, and love where the Chablis flows freely and she is afforded the time to read the papers every Saturday over coffee and an almond croissant.

What makes Sweet Tooth unique amongst McEwan’s novels from The Innocent onwards, however, is the particular way in which the historical or contemporary details — the people, actions, and moments of the age put to good use in Saturday especially — act as awkward ornamentation, superfluous to the main thrust of the novel. Serena informs us:

I also followed the woeful daily narrative. By the middle of the month oil imports were right down, the Coal Board had offered the miners 16.5 per cent but, seizing the opportunity granted by OPEC, they were holding out for 35 per cent and were starting their overtime ban. [...] But I didn’t care.

As ever, there is good reason for this leaden specificity. McEwan has crafted another unreliable narrator novel, Serena having been moulded from the same clay that made Atonement’s Briony Tallis. While making her introductions, Serena notes, “I won’t waste much time on my childhood and teenage years,” which should in itself be a warning that all is not quite right here. And, much like Atonement, information pertaining to the necessity of this jarring prose has been deliberately withheld, to be revealed in the novel’s concluding phrases in a manner devotees of McEwan will be rather familiar with, and in the end is somewhat if not totally satisfying.

Sweet Tooth’s other lead, Tom Haley, is problematic too in a different sense because of his status as an agent for McEwan. In previous works, McEwan has excavated parts of his personality in order to create proxy characters. Amsterdam’s symphonic composer Linley certainly parrots McEwan — an author of libretti for two of Michael Berkeley’s operatic works — when he complains of the imprisonment of music in the academy, adding that “when the definitive histories of twentieth-century music came to be written, the triumphs would be blues, jazz, rock, and folk,” since these forms “amply demonstrated that melody, harmony and rhythm were not incompatible with innovation.”

Similarly, Saturday’s Henry Perowne, a neurosurgeon, shares with the author his liberal, anti-totalitarian interpretation of the impending effort to remove Saddam Hussein by force in early 2003. Perowne also seems to speak for McEwan — whose work has been resolutely rationalist in its outlook, transcendent without falling back on the supernatural or fantastical — when he issues a condemnation of the worst excesses of magical realism:

What are these authors of reputation doing — grown men and women of the twentieth century — granting supernatural powers to their characters? He never made it all the way through a single one of those irksome confections. And written for adults, not children.

But where Perowne’s profession does at least grant him some remove from McEwan, Haley as a writer cannot help but seem like anything other than a ridiculously self-indulgent creation. His status as a stand-in for McEwan is far from subtle. Haley’s short stories are authored in McEwan’s controlled, lucid style, where singular and seemingly trivial incidents become turning points, resulting in previously unforeseen consequences for the protagonist and those around them. Indeed, whole chapters of Sweet Tooth are dedicated to Serena running her critical eye over Haley’s early short stories, or perusing the papers for glowing reviews of his debut novel, as if McEwan himself is revising his own past, reflecting on the writer he used to be.

Haley comes to write for Ian Hamilton’s literary journal The New Review, in which McEwan made his name in the 1970s. McEwan’s publisher at Jonathan Cape, Tom Maschler, accepts Haley’s debut novel, From the Somerset Levels. Martin Amis even makes one or two off-stage appearances, purportedly “so funny” at a reading of his “obscene, cruel, and very funny” novel The Rachel Papers that “he had to pause now and then to let the audience recover.” Haley, also like McEwan, is a student at the University of Sussex, and defends his new college, “his place,” as being “more ambitious, more serious, more enjoyable” than the more traditional Cambridge which Serena attended:

The tutorials were demanding. Two essays a week for three years, no let-up. All the usual literary studies, but on top compulsory historiography for all newcomers, and then for me, by choice, cosmology, fine art, international relations, Virgil, Dante, Darwin, Ortega y Gasset. [...] Sussex would never have allowed you to stagnate the way you did, would never have permitted you to do nothing else but mathematics.

Ultimately Sweet Tooth is thus, for all its faults, a clear expression of an England McEwan knew and wishes for us to encounter. Haley meets Ian Hamilton in the Pillars of Hercules pub in Soho, for this was an old haunt of McEwan, Amis, and the other members of that sparkling literary generation, where their conservation too probably patrolled “endlessly the tiny perimeters of a minor detail,” the meaning of lines at the conclusion of Larkin’s The Whitsun Weddings. Serena’s existence too is dominated by the literary scene, her employers recognising the importance if not the beauty of English civilisation enough to fund writers clandestinely as part of the ongoing Kulturkampf with the Soviet Union.

It is an era — of a benevolent state generously funding the arts (and indeed the artists) for reasons both transparent and ulterior — whose time is passing. Indeed, in a bankrupt Britain beggared by austerity, it may even have passed completely. Either way, McEwan once more has crafted us a record worthy of our attention.

Shares