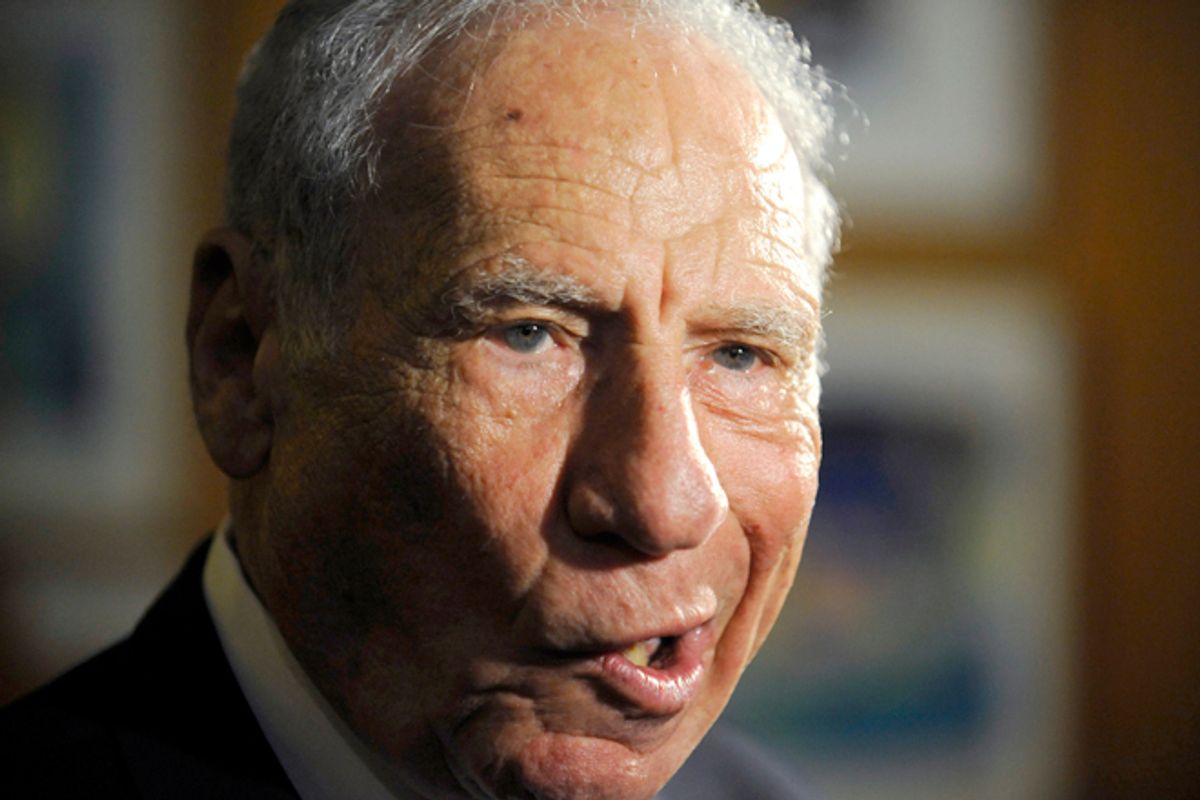

Mel Brooks needs no introduction, but here it goes anyway. The man born Melvin Kaminsky started his career in the 1940s working Borscht Belt nightclubs in the Catskill Mountains, first as a musician and later as a comic. In the 1950s, he wrote jokes for Sid Caesar’s “The Admiral Broadway Revue” and “Your Show of Shows.” In the 1960s, he created the TV spy spoof “Get Smart” and devised the enduring 2,000-Year-Old Man with his friend Carl Reiner.

He made the transition seamlessly to filmmaking, winning a screenwriting Oscar for his first feature, “The Producers,” in 1968. Later he skewered the Russian Revolution with “The Twelve Chairs,” westerns with “Blazing Saddles,” universal horror with “Young Frankenstein,” and science-fiction franchises with “Spaceballs.” Throughout his 60-year career, Brooks has developed a unique comedic style that bridges the highbrow and the low, the literary allusion and the fart joke, the sentimental and the outraged. That's made him a welcome presence in both the art house and the dorm room. His films can be silly, but there is often a bite to the jokes: Brooks has stared down some of the worst atrocities in human history — the Holocaust, the Inquisition, American slavery — and chuckled.

Now well into his 80s, Brooks is entering a retrospective period in his career, with awards and appreciations coming in by the truckload. Next month, HBO will air a new special about his career, followed by an episode of PBS’ “American Masters” in May and an AFI Lifetime Achievement Award in June. Following the rerelease of the “Mel Brooks Collection” early this year (the set, which collects eight films on Blu-Ray, was originally released in a slightly different form in 2009), Shout! Factory has gathered up four DVDs’ and one CD’s worth of archival Mel Brooks material on “The Incredible Mel Brooks: An Irresistible Collection of Unhinged Comedy.”

The new set shows Brooks at the top of his game. He trades quips with Johnny Carson and Dick Cavett, dreams up bizarre jokes on “Get Smart” and “Inside Danny Baker” (his imaginative but, sadly, failed 1963 TV pilot). He talks at length about each of his films and even croons the theme song to “High Anxiety”… in French. Spanning the full length and breadth of his career, “The Incredible Mel Brooks” makes clear that one of Hollywood’s sharpest wits has lost none of his humor, comedic agility or memory. During our conversation, Brooks was quick with comebacks and punch lines, tossing out stories about Sinatra, Hitchcock and other celebrities while maintaining a congenial zaniness that has been the Mel Brooks touchstone for nearly three-quarters of a century now.

How are you this morning?

I’m pretty good, Stephen. Can I call you Steve, even though it’s a PH instead of a V?

You can call me anything you like, as far as I’m concerned.

All right, I am going to call you Calabria. I think it’s a province in the south of Italy. I like the mellifluous flow of it.

Can I call you Mel? Or is it Mr. Brooks?

Let me tell you this cute story. I had just met Alfred Hitchcock. I was really stunned. My God, he was a legend when I was just a kid. So I got to meet him and I was asking his advice on a movie I was making called “High Anxiety.” It was all based on his films. So I was talking to Hitchcock, and he said, "Mel, I think what you should do …" And I said, "Al, call me Mr. Brooks." He looked at me like I was a shithead. But then he took a moment, and he burst into laughter. "Call me Mr. Brooks. I like that." OK, Calabria, what have you got on your mind?

First of all, what part did you play in putting this together?

Day and night, every day and every night, I was at Shout! Factory. I love them. About a year ago, they came to me and said, We want to do a Mel Brooks collection. I said Fox did it. They did a beautiful Blu-Ray box set of all my movies — a great thing. Shout! Factory said, No no, we want to do the oddities, the odd Mel Brooks, the Mel Brooks from the Johnny Carson show, the Mel Brooks from early appearances on the Milton Berle show, the Mel Brooks that few people have seen. I said OK, so we began working about a year ago, and just last week or two weeks ago, we polished off this box set. And believe me I didn’t come up with the title, although I like it. “The Incredible Mel Brooks: An Irresistible Collection of Unhinged Comedy.” It’s a little too … effusive, if you will. They went everywhere looking, which they always do. In addition to the DVDs, they’ve packaged a CD of just audio. I don’t remember this, but they found a clip of me singing “High Anxiety” in French. In French! I speak a little French, so it’s not so bad. It’s good stuff. There’s a nice little book that comes with it, with wonderful articles by Robert Brustein. Gene Wilder did a lovely piece. Bruce Jay Friedman, a friend of mine who’s a very good writer, did a little encomium on me. And Leonard Maltin, who I really respect vis-à-vis cinema. On the first cut of the first disc, you see me and I am Hitler. I am doing the Hitler rap, surrounded by beautiful girls. I’m sitting on an elephant and singing about how the Nazi party came to be. It’s pretty nutty. The set doesn’t have a chronological format. It’s kind of a haphazard collection of things I’ve done through the years. Some of them are really good and some of them could be boring, who knows. I don’t know. I can’t be the judge of that.

There’s a fantastic clip of you singing “America the Beautiful” as Frank Sinatra.

When I did “High Anxiety” [which includes a scene of Brooks crooning the theme song], I got a note from Sinatra. He said, "Mel, I’m serious. If I can’t make a date at the Sands for some reason, if I’m sick or stuck in traffic or whatever, you’ve got to sub for me. You are me as a Jew." I said, "You got it!" Let me tell you one joke, Calabria. I don’t know if it’s in the boxed set. I think it’s in the Dick Cavett part. True story: Frank told me it was true. Don Rickles opened for him in many places. This may have been the Sands in Las Vegas. Don had just started and was a kid. He said to Frank, "I said I got a beautiful girl. She’s really gorgeous. She’s a chorus girl. And Frank, if you would just stop for 10 seconds or a minute and say hi. Just acknowledge me. Please." So Frank said, "OK, I’ll do it." So Don opens for him, and he’s very funny. Frank is, of course, incredible. He wows them. And Don immediately gets his table out front, and he’s having a drink with this girl. Frank comes over as promised, and he says, "Hey, Don Rickles. How are you doing? Who’s this beautiful girl?" And Don says, "The fuck’s a matter with you? Can’t you see we’re talking here!" And Frank said he just collapsed. But that’s Don.

I know you’ve said you’re a writer first, but as a director you have such a good eye for older cinema, satirizing westerns, old black-and-white horror, even silent movies.

If you saw “Frankenstein,” the first James Whale picture, or “Bride of Frankenstein,” you’ll see that the style of acting in “Young Frankenstein” is absolutely dead on. We never blinked. We played it very real: the sets, the costumes, much of the dialogue. It was very real. As a matter of fact, in “Young Frankenstein,” I forgot the guy’s name who had the original machinery from the original “Frankenstein,” the machinery that was in the laboratory that zzz-zzz’s controlled the electricity and all that. He had all that stuff in a garage in Santa Monica. And I begged him to let us use it, and he said sure. So all that was real — the exact stuff that James Whale used in the original “Frankenstein.” In “Blazing Saddles,” I made sure they had tin plates and tin mugs. Everything has to be very real, and the dialog had to be very real — except for where I wanted to switch it. And that was only a bizarre line or two. Harvey Korman has a thought about how to upend the government and take over the state. So he says, “My mind is aglow with whirling, transient nodes of thought careening through a cosmic vapor of invention.” And Slim Pickens says, "Ditto.” “Ditto? You provincial putz.” It’s stuff like that that strays. I just desert the truth for a moment or two of comedy, which makes it work. But if you weren’t real in every other aspect of it, then the movie wouldn’t work. It had to be very real.

The humor in “Blazing Saddles” especially has a lot of bite. It’s very angry, despite its silliness.

It is. We had a little choo-choo train that was running alongside that movie called racial prejudice. We used the N-word. I don’t think you could do that today. I don’t think you could do a new “Blazing Saddles” using that word. I think it would be forbidden. But it worked. It really worked. And one of the Johnsons says, you can’t park that animal here, and Mongo just hits the horse and knocks the horse out. You couldn’t do that today, not with the animal rights people. I am so lucky that everybody was asleep at the switch and I was able to sneak that picture in. I remember Ted Ashley was running Warner Brothers at the time, and we had a sneak preview at the Embassy on Wilshire Boulevard here in California. There were about 2,000 people there. It was incredible. I’m not just bragging. I’m telling the truth. It was nonstop screaming laughter. So Ted Ashley pulls me into the manager’s office after the movie. He was there with his fiancée or something, and she was appalled at everything. He says, You can’t say the N-word. I got a legal pad and pen. OK, the N-word, out! Then he said, you can’t punch a horse. OK, that’s out! You can’t hit an old lady. OK, out! The farting scene must go! Out! I think there were 21 or 22 notes that he gave. I said, it’s all out! He wanted to change the whole thrust of the picture. So he left and John Kelly was there, who was running the movie division of Warner Brothers. I folded up the notes that I had and threw them across the room into a wastebasket. And Kelly said, good filing. And I never changed a thing.

You devote a lot of time on “The Incredible Mel Brooks” to discussing your movies in detail.

I like what I do here at the end of every disc in the new box set. Those DVDs have these little sections called “Mel and His Movies,” about 15 or 20 minutes each, where I explain why I did those movies, how I did them, what I regret in terms of cutting things I should have left in, and how much I loved working with Madeline Kahn and Slim Pickens and Gene Wilder and Marty Feldman. It could be Cinema 101 for kids who are interested in a movie career. And Hitchcock. He was very helpful to me [on “High Anxiety”]. Every Friday, he’d invite me over for lunch and a notes session for what I had written that week. He was my rough editor on the script. He’d cross something out and say no good. And he’d add something and say you forgot this. He was such a good amanuensis, such a good help in making the script. I should have given him screenwriting credit. But I did dedicate the picture to him. And he had bad knees. We used to work in one room, and then we’d go to the next little dining room in his bungalow to eat. Usually it was roast beef, baked potatoes, stuff like that. He ate well. So one time I was there with an assistant of mine, and we’re all having lunch together. And Alfred Hitchcock is in the doorway and he got jammed a little bit. His knees hurt, and he was stuck in the doorway. So I got up behind him and I banged him in the ass with my knee and pushed him through. Come on, Al! I’m hungry here! I didn’t know what he would do. That was really a little… obstreperous. I never should have done it. He just turned red and screamed for about 10 minutes in laughter. Your nerve! Your nerve! He loved it. He loved being treated like a buddy. I really had a good time with him. I miss him a lot.

Between Hitchcock and Sinatra — both of whom seem like they’d be hard to please — you’ve won over a lot of tough people.

These are tough guys. It’s not easy for them to give you a thumbs-up. They would prefer to say get out. Just get out of my office, leave me alone. They’re tough guys. But they’re great guys and they’re uniquely and historically talented. As far as directing movies is concerned, Hitchcock never won anything. He never got an Oscar. Well, maybe he got an honorary Oscar. But he was the best director. He knew what he was doing. It’s an art, and he was the greatest artist at it.

You mentioned the Hitler rap, and there’s another sketch on “The Incredible Mel Brooks” where you play Hitler. You’ve portrayed him often throughout your career. What does it take to play the most evil man of the 20th century?

I don’t know. After all the people that he was responsible for killing and after utterly destroying half the world, I just thought the only weapon I’ve really got is comedy. And if I can make this guy ludicrous, if I can make you laugh at him, then it’s a victory of sorts. You can’t get on a soapbox with these orators, because they’re very good at convincing the masses that they’re right. But if you can make them look ridiculous, you can win over the people. I think that was the thrust of it. I knew I could have fun with him, with his little mustache. I saw Charlie Chaplin do it in “The Great Dictator.” I knew this was it, this was the road, it can be done. Chaplin just showed the way.

How do you make outrageous humor out of atrocities like the Holocaust and the Inquisition?

These things did happen in history, so let’s never forget, even though you might be laughing. It’s amazing how we survived all these incredible, horrible occurrences. But somebody had to do make jokes about it. The job was open. Nobody was doing that job, so I’m going to take it.

One thing that’s clear on this set is the chemistry you have with other comics, especially Johnny Carson.

The great thing about Johnny Carson was he was a little audience. He just loved to listen. And he wasn’t like some of the other late-night hosts, just waiting for an opportunity to jump in. Not Johnny Carson. He watched and loved it. He adored really good comedy. Adored it. And I see Carl Reiner every other night. We’ll have dinner together and talk. I’ll visit him and we’ll watch television. He lost his wife, I lost my wife. We’re widowers together. We’ve been friends for more than 40 years. And he says the same thing: Johnny Carson was the only late-night host who really listened and enjoyed your appearance. Johnny loved Carl Reiner.

That definitely comes through. You bounce off each other so well.

The give-and-take was incredible. We’d have such great fun together. He was the best. I miss him. OK, Calabria, keep talking. I’m eating a pomegranate. It’s not easy. You gotta eat every little one and spit out every little seed. It takes an hour to eat a pomegranate, unless you want to chew it all up and swallow the seeds.

With all these awards and television specials coming up, do you look back and think, I wish I’d had a chance to do this or do that? Maybe a script that didn’t get made or a pilot that didn’t get picked up?

Sid Caesar kept begging me to appear as a character on “Your Show of Shows.” I never did. And I should have. I never should have been scared, but I was a kid writing for Sid Caesar but he was so good. And Carl Reiner was so good and Imogene Coca was so good. I didn’t think I could compete with them. But I should have taken a chance. Later I did jump into being in my movies. In “Life Stinks,” I took the lead role and I loved it. Also, you don’t realize that people come and go. I had no idea that my friends Gilda Radner and Madeline Kahn would be dead at such an early age. Had I known that, I would have spent so much more time with them and just enjoyed their company and their beauty and their talent and their wonder. You learn these things later. They were great people. They left too soon. I love Madeline’s rendition of “I’m Tired” [in “Blazing Saddles]. I wrote that for her. I knew what she could do. And man, she really rocked with that — little things like leaning against the top of the set and missing with her hand and nearly falling. I watch it over and over again just to enjoy her genius.

Have you officially retired from making movies?

That’s a good question. I’m not sure. First of all, it’s anathema to me to get up at 5:30 in the morning. If you direct a movie, you have to be there before everybody. It’s so hard physically. And then what do you get? In California, when you make a movie, you get a breakfast burrito. It’s beans, it’s rice, it’s a soft-boiled egg smashed in there with some ham. That’s your breakfast. You wash it down, like those cowboys, with a tin cup of coffee. I’m kidding about that. That’s not so bad. But you have to take care of everybody on the set, from the costume designer to an extra asking where should I stand. Not there. There. Perfect. Get some chalk, make a little X, and you stand on it. You have to give everybody the respect and attention that they want to have a good, happy set and get results. You have to be as nice as you can be to everybody, and it’s a big job. It takes a lot out of you.

So it’s not so much the creative challenge as the physical challenge.

Every actor will come up to you at some point during the movie and say, I’d like to change this section or this line. And you have to take the hour or two to talk them out of it, because it took a year to write and in 20 minutes they’ve decided that they have a better line or a better attitude. You don’t want to hurt their feelings. It’s all hard. And then you have to get up in the dark and you have to drive out to some place. “Robin Hood: Men in Tights” was way the hell out in the Valley somewhere. It took me an hour to get out there. I had to get up at 4 a.m. because I had to get there by 5:30 when the sun was coming up to know where to put the camera and what we were going to do that day. It was hard. It’s physically very hard to direct a movie. Alfred Hitchcock said to me one time that he directed “Psycho,” I think it was, with one eye closed. What kind of craziness is that? He said he wanted to see just what the camera saw and nothing else. I tried it on the next picture I was doing. For about 10 minutes I tried this crazy thing, but I got a headache. I don’t know how he did it. I remember when he watching “High Anxiety” with me. We were watching a very rough cut of it, and he said, there were 12. I said, what are you talking about? Twelve what? The rings. In the shower. The shower rings. I had eight in “High Anxiety” and he says there were 12. That guy.

Shares