WHEN RIDING THE BUS to the University of Texas campus a few years back, I became suddenly conscious of the fact that the cover of the book in my hands depicted a stark white fist clutching a hammer against a black background. And the title: The Wages of Whiteness. It was enough to raise a few eyebrows. At the time, I was delving through the available literature on blackface minstrelsy, as part of my exams for the Ph.D. program in American Studies. Looking back on this brief bit of extreme self-consciousness, I think my gut feeling was right, because — at best — the topic of minstrelsy in America is a discomfiting one, not typically broached in public.

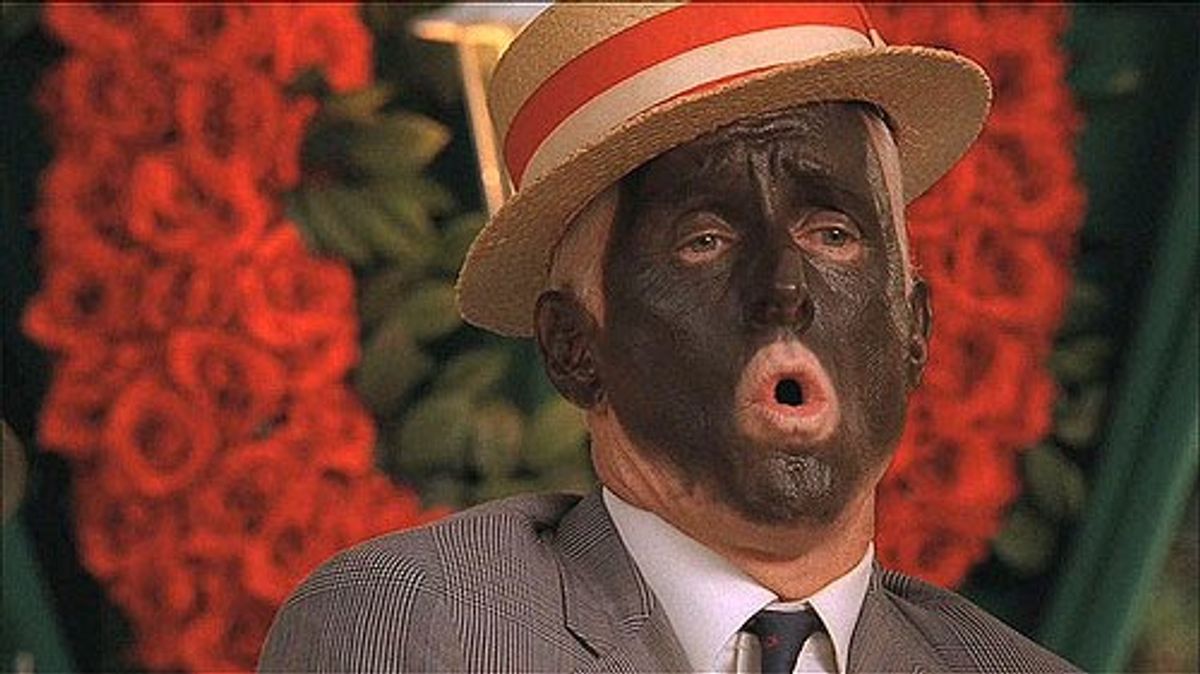

David Roediger’s The Wages of Whiteness — not, of course, a racist tract — is one of several academic studies about the idea of “whiteness” that first emerged among the nineteenth century American working classes. Roediger’s book, along with Noel Ignatiev’s How the Irish Became White, Eric Lott’s Love and Theft, and Alexander Saxton’s The Rise and Fall of the White Republic, expanded on what is known as New Labor History (Herbert G. Gutman et al.) by taking race as central for understanding the working class. They study blackface minstrelsy as a way to ascertain how immigrants and others fresh from the farm were indoctrinated into the discipline of industrial wage labor during the antebellum period. They assume the wealthy and powerful had an interest in distinguishing, for this audience, how wages that barely provided subsistence in the burgeoning industrial economy of the North differed in a substantive way from the enslavement of blacks in the South. Hence, the creation by white performers in blackface of so many stereotypes of African-Americans as lazy, sensual, libidinous — traits recently arrived immigrants were encouraged to disavow in order to ascend into the ranks of “whiteness” and its promise of dominion over the Other: the black, the Chinese, the Hispanic, the unassimilated.

This was the argument 20 years ago, and in its wake followed a reinvigorated scholarly discussion of the politics of black commercial entertainment in America — which, though it takes many forms, cannot be disentangled from its origins in those first black performers who, witnessing the success of their white forebears on the stage, donned the burnt cork both for whites and for fellow African-Americans.

Like Roediger’s book, the cover of Yuval Taylor and Jake Austen’s Darkest America: Black Minstrelsy from Slavery to Hip-Hop employs a similar high-contrast image, though in this case the mano blanco is less reminiscent of a “power” salute than Mickey Mouse’s glove — a not-wholly-inappropriate association, given the very early Disney cartoons. In a blurb on Darkest America’s back cover, James Galvin states, “Before [. . .] this important book, the minstrel era had regressed into vague and dusty African American history; its aftereffects were felt but little understood,” ignoring decades of work by black cultural critics (and some historically-minded artists) and academics in labor history, film studies, and popular music. Some of the academic texts on this topic are, in reality, fairly well known; Lott’s book apparently impressed Bob Dylan enough that he copped the title for a 2001 album. And while Galvin may not be aware of this work, Taylor and Austenvery much are. In fact, the significance of their project lies in its scope and synthesis of extant scholarship and that, as a popular press book, Darkest America can do things an academic study cannot: its chronological sweep can be broader, its linkages between past and present looser, if still quite compelling. The book will thus help further disseminate a broad swath of ideas and topics that are common among specialists to those outside the field, like the fact that African-American audiences were avid patrons of black minstrels, or the significance of Bert Williams’s career in American popular song; it calls to mind the way Howard Zinn popularized several generations of left-wing historians’ work with A People’s History of the United States.

Taylor and Austen focus entirely on black minstrelsy, or the legacy of black entertainment that reaches back to African Americans donning blackface in the nineteenth century and the perpetuations, additions, and modifications of that tradition up to the present day — not whites donning burnt cork, as with the “whiteness” scholars mentioned above. Rather than Lott’s interest in whites’ “love and theft” of black culture, Taylor and Austen zero in on the “love and hate” relationship between African-Americans and the minstrel past of black entertainment. They open and close the book with contemporary examples: the comedian Dave Chappelle’s decision to walk away from his eponymous Comedy Central show due to discomfort over the response to a blackface character he’d created for a sketch, and the antagonistic relationship between the filmmakers Spike Lee and Tyler Perry. In between are a series of case studies detailing old-time black minstrel troupes, the Zulu Krewe of New Orleans’ Mardi Gras, “coon” song virtuoso Bert Williams, Stepin Fetchit, Amos n’ Andy, Bill Cosby, seventies sitcoms like Good Times, “plantation nostalgia” in pop music, gangsta rap, and Zora Neale Hurston. In each instance, Taylor and Austen attempt to treat their subject with an even hand, noting that, “[t]hough there are many challenges to approaching the history and legacy of this thorny subject, one refreshing aspect of this study is that it doesn’t ask the student to choose sides, identify villains, or make declarations of good and evil.” And they offer this conclusion regarding the long fetch of black minstrelsy:

This timeless facet of American cultural history has spawned impressive works of both hilarious, shameless abandon and poignant, deliberate condemnation.

The back minstrel tradition is funny that way.

It’s a nice note to end an ambitious book on. But along the way, there are some grave problems. The first is this business of not having to “choose sides” while in the same breath claiming that their study is “refreshing”; Taylor and Austen not only adopt a smug rhetorical pose — here and throughout the book — they suggest that previous scholarship on black minstrelsy mistakenly does ask the reader to “choose sides.” They say their “ire” is “reserved for scholars who knowingly truncate quotes, ignore inconvenient data, and rewrite history to make black minstrels of yore fit into contemporarily acceptable models.” On the surface, this seems like an admirable attitude for scholars dealing with a contentious subject. In practice, however, Taylor and Austen’s targets are often made of straw (“most historians” and “contemporary writers” are particular favorites) and the historians and critics they do name, for the purpose of discrediting them, are shorn of context. While they’re happy to suspend judgment of Bert Williams’s use of blackface because of his historical context, they don’t extend the same latitude to Williams biographer Ann Charters, who interpreted his stage act as a result of cultural coercion. Anyone writing about this topic in 1970, sympathetic to the Civil Rights movement, Black Power, or what came to be known as “Black Studies,” would have found utterly unconscionable to assume that black entertainers might haveliked playing the “coon.” Charters wrote:

When Bert Williams began his career in 1892, he found he had to conform to a theatrical convention that in many ways crippled his talent and limited his achievement. As a pioneer he was forced into a blackface role he detested.

That second sentence may be historically wrong, but the political reasons for such a reading elude Taylor and Austen.

And it isn’t just the historians who paved the way for their work that Taylor and Austen disdain — it is today’s writers, as well. “To be categorical and plain, Bert Williams treasured the minstrel tradition. But this fact is too horrifying for contemporary writers to face.” They do not bother to actually name these adversaries for three and a half pages: the authors of three biographies and one novelization of Williams’s life. They admire Eric Ledell Smith’s 1992 Bert Williams, but dismiss it as the product of a “small press” (the publisher, McFarland & Company releases about 150 new titles per year). These are signs of intellectual laziness and scholarly immaturity, and the source of almost interminable reader frustration. In eschewing the more specific language of academic theory, Taylor and Austen have no recourse but to the vagaries of vernacular concepts like “dignity.” Inevitably, when you try to ascertain whether or not some thing or some one is “dignified,” the result is less than objective. To paraphrase the title of another of Howard Zinn’s books, you can’t be “objective” at a minstrel show. You can laugh or rage, tear up or grow indignant — but in the end you always choose a side, no matter how much Taylor and Austen wish to suspend that fact.

Although very little original research went into Darkest America, the authors insist on debating every academic or critic who ever put pen to paper on the topic of minstrelsy. Their few contributions are used primarily to further beat up their predecessors. For example, they found that a particularly grotesque clip of bug-eyed black comic Mantan Moreland, one often used in documentaries and montages of black minstrelsy, is, in fact, from an all-black 1942 film and not, like his contemporary Stepin Fetchit, an example of a token black clown in a white Hollywood film. They mention this discovery in two different chapters, in order to point out that Bill Cosby, Robert Townsend, and Spike Lee were, in turn, insufficiently aware of the fact.

The penultimate chapter, on Zora Neale Hurston, is the only section not in something like chronological order. It is there to set up their final chapter, on contemporary film directors, pitting the New Yorker Spike Lee against the Southern Tyler Perry. Implicitly, Lee is an analog for Hurston’s fiercest critic, the novelist Richard Wright. And Perry is, of course, the modern-day version of Hurston; Perry has himself drawn the comparison. By leaning favorably towards Hurston, and disavowing Wright as a scold — a writer who loved the cultural highs and the lows, but disdained the middle — and then speaking positively of Perry (a filmmaker whose audience is almost entirely black), Darkest America’s two white writers get to pull one of the oldest tricks in the hipster handbook: to concurrently denigrate middle class values and express solidarity with the vulgarities of the low, a move assisted by a rhetorical “crossing the tracks.” That they also get to disdain the black middle class is just gravy; the important point here is that Taylor and Austen are down. Maybe Taylor and Austen are genuine, un-ironic fans of Diary of a Mad Black Woman. Like Norman Mailer in his essay “The White Negro,” Taylor and Austen use a rather imaginative (not to mention reductive) vision of contemporary black aesthetics as a means of critiquing the values of the middle class — a group that tends to hold Richard Wright and Spike Lee in high regard, across racial lines. (It’s worth remembering that Mailer himself described his observations as “Superficial” in the subtitle.) Having travelled to the Crescent City as part of their research and witnessing New Orleans’ Zulu Krewe firsthand, Taylor and Austen write:

Though cautious tour guides likely steer visitors away from ‘the hood,’ it would seem that the welcoming spirit of Mardi Gras would blur traditional neighborhood lines, and the crowd was certainly friendly to us.

In his grave, Jack Kerouac nods in agreement to a bebop beat.

These faults aside, Darkest America functions as a fulsome summary of black minstrelsy’s indelible effect on American popular culture. They reference all the key figures and historical debates and their basic conclusions are sound: black minstrelsy is different from whites donning blackface; playing the fool is both a form of bondage (“puttin’ on Massa”) and a means of temporarily liberating oneself from the drudgery of everyday existence; white spectatorship complicates what is and is not acceptable material for a black entertainer. These points all need to be made (and remade for new audiences), because without them we cannot begin to understand the persistence and importance of African American folkways in contemporary popular culture, the pleasures and pains of comedic stereotypes for performer and audience alike, and the consequences of living in a world where the white, mainstream entertainment industry continues to engage in both implicit and outright discrimination, and where minority-owned entertainment businesses often choose to self-segregate in order to monopolize their audience.

Taylor and Austen’s was no small task; we can only hope that another mainstream writer will take up the torch, and address these critical issues more straightforwardly. “Black Minstrelsy,” as the authors have it, “is funny that way.” And Darkest America is an awkward bus ride.

More Los Angeles Review of Books

-

Maria Bustillos on "The End of Men"

Rising together: A corrective to Rosin's "The End of Men" -

Walter Benn Michaels on "What was African American Literature?"

Black and white

Shares