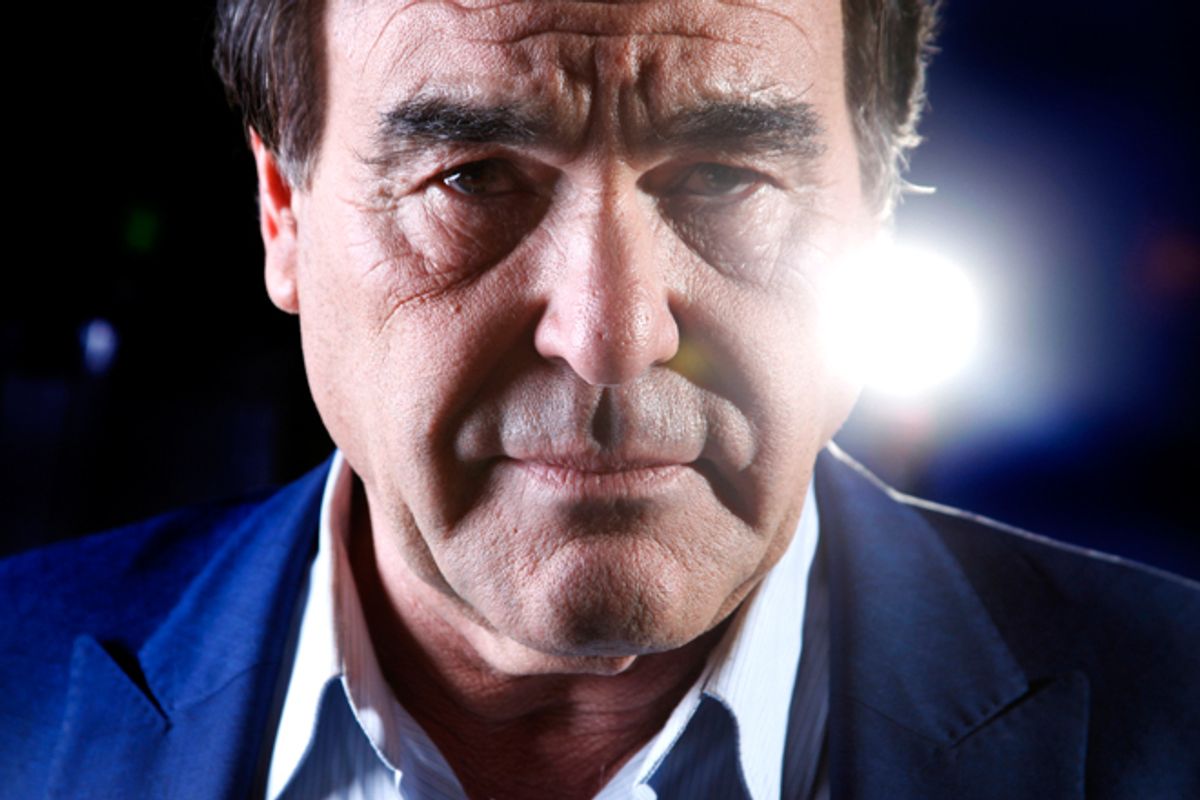

Across a four-decade career in the movie business that has encompassed three Academy Awards, 18 narrative films and several documentaries as a director, and innumerable side projects as a writer and producer, Oliver Stone has been obsessed with one topic: America. Indeed, during what you might call Stone’s classic Hollywood period, from “Salvador” in 1986 to “Nixon” in 1995 – and I don’t exclude such apparent detours as “The Doors” and “Natural Born Killers” – his central subject has been all the ways the United States has driven itself crazy, on both the foreign and domestic fronts, in the years since his own Eisenhower-era childhood.

Given that background, it’s almost surprising that it’s taken Stone this long to tackle a straightforward nonfiction project like his Showtime miniseries “The Untold History of the United States,” which tries to counter the jingoistic mythmaking and obligatory “American exceptionalism” of most public discourse about 20th-century history. That phrase refers to a creed that still holds sway (or so polls suggest) among a large proportion of the U.S. population, although it hasn’t been taken seriously by historians for many years: The idea that America has a special and even sacred role to play in world history, and cannot be compared to other nations driven by the grubby realities of politics and economics.

For left-wingers like Stone and American University history professor Peter Kuznick, who collaborated on this miniseries and the accompanying book, the rhetoric of American exceptionalism is used as a mask to conceal the nexus of money and power – corporate expansion and military empire-building – that really defined America’s rise to global hegemony. While the TV series begins with a scattershot history of World War II, the development of the A-bomb and the transition to the Cold War, Stone and Kuznick’s whopping companion volume from Gallery Books goes much deeper into the past in search of the roots of America’s contemporary dilemmas.

That was partly, Stone told me during our recent conversation in New York, because he had to keep the Showtime series to 10 episodes. It was also because the target audience for the TV show is meant to include high school students, and he didn’t want to drive them away with a potentially confusing exploration of the explosive class politics, rapid economic expansion and abrupt turn toward imperialism that transformed America late in the 19th century. Stone and Kuznick were partly reacting to testing data suggesting that American high school students have a poorer grasp of history than of any other subject; the vast majority, for example, could not identify the social issue addressed by the 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education.

It won’t surprise anyone who has followed Stone’s career to learn that the general tenor of “The Untold History” is one of idealism tempered by outrage, and sometimes the other way around. While he wants to argue that the public conception of America as a nation driven by disinterested idealism and a divine mission is hopelessly flawed, he stops well short of, say, Noam Chomsky’s Cassandra-like pronouncements about the immense evils of our nation. Stone and Kuznick seek to identify heroes and near-heroes, along with moments where things could have turned out differently. To cite one obvious and intriguing example: Had Franklin D. Roosevelt lived long enough to make the decision about bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or had he been succeeded by the progressive Henry Wallace, rather than the hawkish and poorly educated Harry Truman, the rest of the 20th century might have turned out quite differently.

Stone has, to my way of thinking, an overly rosy view of leaders like Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy (and perhaps too of Barack Obama), along with an understandable tendency to focus on the charismatic great men of history rather than the impersonal forces that often drive their actions. Overall, though, I think it’s healthier to take a big-picture view of this project, and of Stone’s whole career. He’s made good movies and bad ones (in my view), but he has consistently devoted his storytelling skills and his moral sensibility to creating a counternarrative to the enormous tide of hogwash that dominates most public discussion of America.

I started my conversation with Oliver Stone and Peter Kuznick in a Manhattan conference room; then, when we weren’t done, continued it in a tanklike SUV conducting them to a radio interview. I finally left them on a sidewalk in midtown, where Stone politely signed autographs for a handful of fans bearing “Platoon” posters.

I don’t know if you guys saw the post-election essay posted this week by Chris Hedges, which was probably the darkest one I’ve come across. He wrote that the liberal class in America was dead – he actually used the word “corpse” -- and said that they’re celebrating the reelection of a president who is essentially no better than the other guy. They both represent factions of the same corporate-imperial power structure. Is that too dark?

Peter Kuznick: Oliver and I differ a little on this one. I say it’s much too dark an assessment. We have a 70-page chapter on Obama that is very critical, because we expect more from him. There are traditions within the Democratic Party that he could identify with much more, and cleave a more progressive path for this country. So we have some hope that in the second term, if there is a popular movement to push him in a more progressive direction, he’ll respond to that positively. And he has done some good things. The healthcare program wasn’t what we wanted to see, but it was much better than what existed before. He has gotten out of Iraq as he promised. He’s very good on women’s issues, on pay equity, the Ledbetter act. So those are good things. We have a much more critical view of Romney.

That said, Obama, as we say, is doing a better job of managing the wounded empire. That’s what we call our chapter on him. We think he is putting a kinder face on the empire, but he is not talking about ending the empire. The people he surrounded himself with, on both domestic and foreign policy, are certainly not talking about ending the empire. Obama said last week in his speech, that the United States is the one indispensable nation. Well, we know who that goes back to, that concept. It goes back to the 1630s. But it also goes back to Hillary Clinton’s statements, it goes back to Madeleine Albright saying that if we use force, it’s different, because we’re the United States of America. That’s an attitude of American exceptionalism that we’re trying to challenge.

Oliver Stone: That’s a good answer, but the argument that I think you’re looking to get is why liberals cannot define themselves, and I think that’s the key argument. I would say that the divide is a big one, because liberals keep attacking liberals. It’s clear to me now, just paying attention during the course of this review process, that certain liberals are going to attack us. Whether it’s Chomsky [attacking us] for the Kennedy approach, or Chris Hedges may not like it for this reason or that reason. But right now the issue between liberals is empires or no empire, pro-empire, or anti-empire.

You know, I hear that Sean Wilentz is coming down with some kind of negative review, and that would obviously raise the issue of where these liberals divide. And if you look at the Wilentz record, from what I gather, it’s very much pro-Clinton, pro-empire. We think, and we agree with Hedges here, that the issue is empire, and we have to stop it. We have to stop the expense and the drain on this country that is going into 800-plus foreign bases. And that’s the main issue, whether Republicans are going to keep running this empire up to its eventual extinction. We’re saying it’s a beast that’s fatally wounded, and cannot work. Obama may prove us wrong because he is a doer, he gets things done. He did promise very strongly that he was going to manage this and make people secure and strong, and that America is indispensable. Don’t assume that he doesn’t mean it. He’s bought into it now. So we are into a period of tremendous tension in these next four years.

P.K.: This divide that Oliver’s talking about, that Chris Hedges was talking about, runs deep in liberalism. That New Deal coalition fractured in the immediate postwar period. You’ve got Truman taking the Cold War liberals in one direction. You’ve got Henry Wallace trying to lead the anti-Cold War, the internationalist liberals in a different direction. Clearly the Cold War liberals won. And that Cold War liberalism dominates the Democratic Party until the 1960s, and then we begin to see an anti-imperial wing developing in the Democratic Party.

O.S.: One key moment for me in my symbolic journey through life is back in 2003, when Hillary Clinton voted for the Iraq War Resolution and Obama spoke out against it. That was a divide between the two candidates, that was for me a key issue. I wonder why Obama, at that point, did not keep going on that track. In my opinion he would have beaten McCain anyway, he had the popular momentum. Something happened. Was it because McCain scared him? No doubt McCain was a supporter of empire, and would have been in five wars by now. But what happened to Obama? Did he take the money, as we’ve heard, from Wall Street, or big Pharma? What happened to his mentality? He won. He was winning on that idea, that momentum of populism and anti-war.

Whatever criticism I may have of this series on a granular level, you’re trying to make the connection, the whole time, between the growth of empire and the growing power of big capital. That’s a very important and dangerous conceptual linkage. How does that synergy work?

O.S.: For the same reason that the atomic bomb has worked. And I’m an outsider, I come late to this. I accepted the atomic bomb for many years. But if you go back now as this newcomer to this ballgame, and you see: That’s the moment where all of a sudden, we are America, we are exceptional. After ’45, we’re right, we’re good, nobody can beat us, because we are the New York Yankees. We’ve got all the cards. And we act like the underdog, which is interesting in our history. Peter pointed this out to me: We keep saying, “We’re encircled by the Russians,” or the Chinese are coming, that’s the latest thing, or the terrorists are overwhelming us. It’s a combination of tremendous self-righteousness and fear, but ultimately it’s our sense of morality. The bomb gives us the right to invent our own morality and makes us better. It’s the only card we play, because if we didn’t have the bomb, we didn’t have the force, the world would have come down on us by now.

I don't know if I answered your question! But the bomb ties to corporations, because it’s about power. Power is what everyone worships in this country, and power was concentrated more and more in big corporations by the 1950s, although in the 1930s many of these corporations were already cooperating with the Nazis. But in the 1950s the corporations grow into the great gray monolith of our society. Eisenhower pays homage to Wall Street, through John Foster Dulles [Eisenhower’s hawkish Secretary of State and a prominent New York lawyer].

As an outsider to all this, I knew about the foreign interventions but I didn't know about the degree under Eisenhower. He's the first one who jumps in abroad, in several countries, much more so than I'd ever thought. So even though Eisenhower warned us about the “military-industrial complex,” to me his grandfather mask falls off.

There are a lot of people in this country who are obsessed with what the Founding Fathers would have wanted, and who try to read the Constitution as this inerrant biblical document. And the thing is that what we have now, what you guys are talking about – a state predicated on imperial power coupled with financial power -- is so far away from what those people imagined.

P.K.: So far away. Because they had understood that they fought a war against colonial power. Americans were very hostile to Britain until the 20th century, till the World War I period, because that was the empire and we were consciously anti-imperial. John Quincy Adams has a great speech that he made on July 4, 1819, in which he says we don't go forth in search of foreign monsters to destroy. He says we might become dictators for the world, but we would lose our own spirit as a nation. And that’s what we think has happened, the United States in some ways has lost its soul as a nation. We started to lose that soul in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We lost it during the 1950s with Eisenhower going from 1,000 nuclear weapons when he takes office to 23,000 when he leaves office, to 30,000 when his budgeting cycle is finished. We lost it in Vietnam. We've lost it repeatedly, but we think it's not all gone. That's why we're fighting to salvage what we can and turn this around.

I was just reading your chapter about the period right before World War II, when Sen. Gerald Nye – a Republican from North Dakota! – leads this investigation of the arms manufacturers, which came close to forcing the nationalization of the entire arms industry. That really struck me, because it’s so inconceivable now. You have a prairie Republican who was basically a progressive, which is inconceivable now. And today, in the era of Halliburton, we just accept that our military economy is a massive private sector for all these huge and secretive companies.

O.S.: Nye was great! But it is inconceivable. I never thought of it that way, but you’re right.

P.K.: It's why we stress it in that way, because it's inconceivable. People have to know that these things were possible in the United States. Americans could think this in the past and do these things.

O.S.: Kids, know that you too can bring a congressional committee! You don't have to worship military generals with fruit salad on their chest. Congress seems to simply waive the right to war, they essentially believe anything the military says. It’s like the Roman Empire and the Praetorian Guard. Our television has been really revelatory to me the last two or three days, covering Gen. Petraeus. I have never seen such encomiums. It's assumed that it's a great soap opera: The guy's a hero and takes a fall because of a woman. It’s like the story of “Coriolanus,” that’s what they want. But the truth is: What hero? What did he do?

Any time you talk about history there’s this tension between, you know, a Marxist interpretation where it's impersonal forces that are driving everything forward versus the great man theory where individuals really have a dominating role. I feel like you strike a nice balance of combining those two things. I had never thought much, for example, about the importance of Henry Wallace. My mother worked for Wallace in 1948, actually, so I knew about him. But I never reflected on how close he became to being president.

P.K.: So your mom was a leftist?

Yes. A union organizer and a Communist Party member?

O.S. What was wrong with being a Communist? Nothing, at least not at that time. One of the great tragedies of America is that there were so many people who were progressive in the 1930s, who went to fight in Spain and do the things that a young man should do. Then you come back from Spain and before you know it you're on the bad side of history. J. Edgar Hoover's after your tail and nothing you did before 1940 is good, even being in the Work Theater Project with John Garfield, it's not good. Could you imagine what torture it is to be a human being in that era? Tremendous soul damage that's being done to America, and what I saw in the 1950s was fearsome. I was terrified. People had to behave, otherwise … Even my father's friends who were liberal, he would make fun of as Communists. But there was only so much fun to be had because your job could be at stake.

Sure. My dad had to sign a loyalty oath to teach at the University of California. He signed it, but he regretted for the rest of his life that he hadn’t taken a stand. To get back to Henry Wallace – he gets forced off the ticket in 1944 and replaced by Truman, even though most of the Democratic Party faithful supported him. Now, if that hadn’t happened, and Wallace becomes president the next year after Roosevelt’s death, does that change history? Does he decide against dropping the Bomb on Japan, and choose a different course with the Soviet Union?

P.K.: It could have. There's no way to know for sure, because you're talking about the forces as opposed to the people. But Henry Wallace was a visionary and he had a different approach to the world than Harry Truman, which was much more in the tradition of Franklin Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt. And Franklin Roosevelt's last cable that he wrote about the Russians was a cable saying, “We might have small disagreements but we're friends and there's no reason why we shouldn't stay friends and work together in the future.” Henry Wallace was not uncritical of the Soviet Union, but he thought the Soviet Union had become more democratic and would continue to move in that direction, while we would become more socialistic. He saw a different kind of balance through competition, friendly competition rather than this kind of arms race and military buildup and confrontation.

I was just about to ask you about the ghost of the Soviet Union, which haunts us to this day. It’s had such a distorting effect on the left, the question of your attitude toward the Soviet Union, how much you condemned it, whether you supported some aspects of what they did, whether you view Stalin as an atrocious monster on the same scale as Hitler or more or less a rational actor. It’s such a big problem when you talk about that whole period of history.

P.K.: It’s a problem that the left in the United States has faced for decades. The Soviet Union has been an albatross around the necks of the left. We’re very measured on that, in the sense that we strongly condemn Stalinist brutality, we don’t ignore that, we don’t soft-pedal it. We think that’s part of the story, but Stalinist brutality was within that sphere — Stalin was intent upon maintaining friendly relations with the United States after the war. Stalin was a strong ally during the war, and it was very much in his interest to pursue that course.

O.S.: There were two chapters that we worked on extensively, but we didn’t finish because we ran out of budget, we had to make it 10 hours instead of 12. The first chapter was about the roots of empire, from the Spanish-American War through World War I. The second chapter was about the 1930s, which fascinates me, and that’s where we get into the communism thing. Woodrow Wilson is the first liberal, so to speak, who goes to war with the Soviets -- he sends American troops to Russia as part of the counterrevolution, which, of course, raises enormous suspicions by the Soviets. He declares America, at last, can be the savior of the world.

P.K. “At last the world knows America is the savior of the world.”

O.S.: Which is an amazing statement for a liberal, but that sets the course for an interventionist policy, it seems to me. And then, long prior to the Soviet Union, and the Bolshevik, anti-God, anti-property revolution, you can trace it back to America’s attitude toward the Communards, in 1870s France. There was such terror in the West about any collectivist activity. All the labor struggles began in the 1880s and ‘90s, with the populist movement. It’s a shame it can’t be in there, but it’s so much to handle for a young audience. We thought we would lose them, so we decided to suspend those chapters in deep freeze. They may come back in an appendix, explaining the roots of this shit.

Is it realistic to believe that if the United States had chosen a different course in the postwar years, and you don’t wind up with that version of Truman Cold War liberalism as the dominant current, that the Soviets would have behaved differently as well?

P.K.: I think there is strong evidence for that.

O.S.: It’s always assumed that they are going to behave like brutes, which may be partly because of the German occupation.

P.K.: Stalin was devastated when Roosevelt died. Averell Harriman [the U.S. ambassador to Moscow] goes to see him, and Stalin is holding Harriman’s hand and crying. Harriman was so moved by the depths of Stalin’s emotion.

O.S.: What’s also interesting is Churchill’s assessment. At the end of his life Churchill says that Stalin kept his agreements. He pointed to that 1944 agreement they had made on Greece [granting dominant influence to Britain and the West, in exchange for Soviet dominance elsewhere]. Stalin didn’t butt into Greece. He was always assumed to be butting into everywhere by the Truman people, but the truth was otherwise. He withdrew from Iran, he withdrew from Turkey, and on Greece he laid off. And he got into a huge split with Tito, what says more than that? He was willing to risk losing a major pro-Soviet movement in Yugoslavia to keep his agreement with the British. That’s putting your words into action.

We need to wrap up, so talk to me about American exceptionalism, which is really your target here. Why is that so important to such a large proportion of people, and certainly to the political establishment?

P.K.: You can’t really deny American exceptionalism without getting slaughtered. Obama tried. Obama said, “I believe in American exceptionalism just like the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism.” Then he got jumped on. Mike Huckabee says that American exceptionalism is the soul of the nation, and if you deny that then you deny America’s soul and essence.

OK, but Mike Huckabee represents crazy people. And the fact is, no major Democratic politician would say that either. Obama may fudge it a little, but neither Bill nor Hillary Clinton would risk denying American exceptionalism. Probably George McGovern is the only presidential nominee of either party who would have done so.

P.K.: Right, and we’re challenging that. We’re saying that the United States is exceptional in certain ways, but the myth is that the United States is different because all other countries are venal and greedy and self-aggrandizing, and the United States goes out into the world because we’re altruistic, benevolent and generous; we care about freedom and democracy. That’s the myth that we’re challenging. We’re showing that the United States is militarily involved everywhere: We have a military presence in 132 out of the world’s 190-some nations. We have 800 to 1,000 military bases, a huge nuclear arsenal, drones. Now we’re trying to dominate land, sea, air, space and cyberspace. We’re going after it all. Total dominance, full spectrum dominance. This is the future, and in some ways it’s a dystopian future. We’ve lost a lot of our freedom and liberty and privacy already, but nothing compared to what they envision 20 years from now.

You were talking earlier about how America always perceives itself as the underdog, whether we’re talking about the Cold War or about a conflict with al-Qaida, this tiny, fragmented organization with a few hundred members. That’s always struck me as such a paranoid conception, and I wonder whether American exceptionalism is the other side of the coin, a different manifestation of that same paranoia.

P.K.: Just look at the irrationality of our policy. We went into Afghanistan to get al-Qaida, because of 9/11. There are now probably 50 al-Qaida members left in Afghanistan. We’re spending $100 billion a year militarily to defeat them. That’s $2 billion a year for every al-Qaida member in Afghanistan. Osama bin Laden didn’t say he was going to defeat us militarily. He said he was going to get us to bankrupt ourselves by the stupidity of our responses, and he’s done that.

O.S.: You can also say, to answer your question, that if you’re not No. 1 in our book then you’re nothing. So the quest for full-spectrum dominance, as Peter said, is very serious for the world. In 2006 the United Nations voted not to militarize space, and the vote was 166-1. That’s a key measurement, the fact that we are an outlier. Bush pulled out of an arms treaty with the Russians. He pulled out of the Kyoto Accord. He pulled out of the International Criminal Court. Obama has made no effort to rejoin any of this. So the situation is that we are an outlaw, we are an outlaw nation. Because we’ve got the weaponry we’re acting the bully. You could argue that a bully in high school is paranoid, because if he’s not No. 1, on top of everything, he feels small.

Throughout your career, Oliver, it seems to me that you’ve been battling with the question of patriotism on a personal level, almost as an internal and psychological matter.

For me it was, yeah. I believed in America. My father was a Republican, and I was brought up that way. I went to Vietnam and served. I didn’t get to the bottom of this in my head until after Reagan, right around that era. It took a long time after Vietnam; you don’t just have a St. Paul on the road to Damascus moment because you go to Vietnam. That’s what people always say: He went to Vietnam, and he’s been paying for the sins of that ever since. That’s a simplification of something that is very complex.

P.K.: In “Born on the Fourth of July,” Tom Cruise’s character illustrates Oliver’s idea that we need a new definition of patriotism and a new definition of heroism. We’re not repudiating patriotism, we’re just redefining it.

O.S.: It’s been a torture to live through this history, but it’s interesting. It’s heavy, you know?

“Oliver Stone’s Untold History of the United States” airs Monday nights on Showtime.

Shares