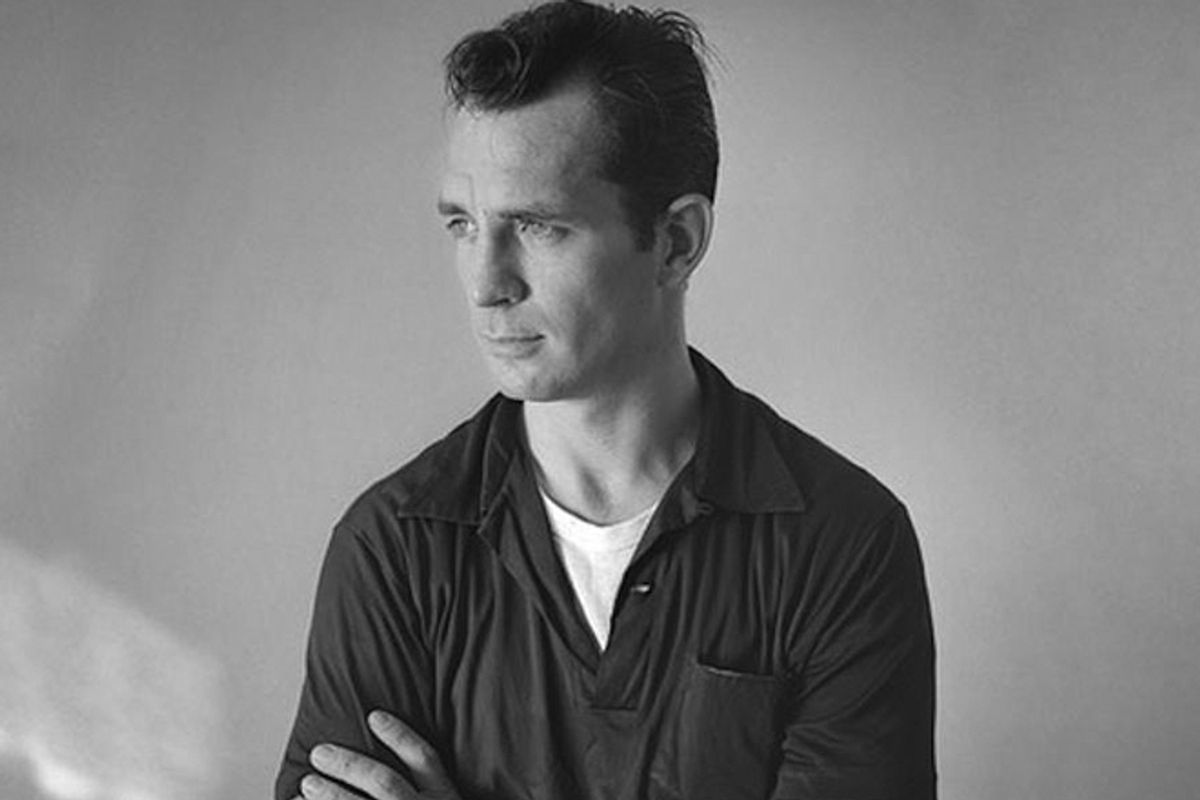

In December, a film adaption of Jack Kerouac’s "On the Road" will hit theaters — featuring Viggo Mortensen, Kristen Stewart, Garrett Hedlund and Kirsten Dunst — providing two great literary opportunities: introducing Kerouac to a new audience, and reexamining the author's legacy in literature.

When "On the Road" was published by Viking in 1957, Jack Kerouac became an overnight sensation, a literary figure who was met with the kind of polarizing emotions of disdain and love that, today, one would have to look to sports to find the worthy contemporary comparison (i.e., LeBron James or Tim Tebow). His fame came, in part, from a New York Times book review by Gilbert Millstein, which hailed the book's publication as a "historic occasion." Millstein wrote, “in so far as the exposure of an authentic work of art is of any great moment in an age in which the attention is fragmented and the sensibilities are blunted by the superlatives of fashion.” Millstein compared "On the Road" to Ernest Hemingway’s "The Sun Also Rises," because both works introduced cultural movements: the Beat Generation and the Lost Generation.

In 1957, "On the Road" flew off the shelves, but many critics panned the book, calling Kerouac naive and pedestrian. According to Dan Wakefield's "New York in the Fifties," Orville Prescott, the principal daily book critic at the New York Times, was on vacation when Millstein wrote the review. When he returned, Prescott was outraged; he hated the book. But Prescott’s revulsion was just the beginning. Kerouac was met with heavy criticism from Norman Podhoretz, Norman Mailer, Dan Wakefield, James Baldwin, John Updike and Seymour Krim, to name a handful. Most famously, Truman Capote said Kerouac wasn’t writing, he was merely typing, commenting on Kerouac’s idea that the first thought was the best thought.

“Jack suffered the same misrepresentation and misunderstanding that many original people do,” says David Amram, American composer and friend to Kerouac. “[Kerouac] said to me over and over again: ‘I’m an author, Davey. Why don’t they read my books? They’re dismissing me.’”

Kerouac felt the criticism was unfair and personal. He told Amram that the literary elite just thought of him as blue-collar trash. Amram tells me, “He was supposed to be the man of the hour, but instead of dining with patches on his sleeves, smoking a pipe and becoming the tortured intellectual of the month, he remained exactly what he was. In the highly competitive world of the literary scene, they were horrified to see that the new Mr. Big was wearing the same flannel shirt that everyone in Lowell [Massachusetts] wore and still wears today.”

Fifty-five years after "On the Road" was originally published, has hindsight improved the author's literary reputation among a “literary elite”? Many of the original critics of "On the Road," including Mailer and Wakefield, changed their tune somewhat: Wakefield began to read Kerouac’s other work, like "Desolation Angels," and accepted that Kerouac was important in defining a cultural movement, a moment in history, and sparking a new way of perceiving the world. In universities across the country, Kerouac is acknowledged for his myth, his legend — wearing the crown of the Beats.

But should Kerouac be considered one of the 20th century’s great writers? Does he deserve to be admired and studied for his craft?

Wakefield tells me, “I don’t think he’s one of the 20th century’s great writers. I think he was a great figure. His work has inspired a lot of people. There are other books that aren’t great books that inspire a lot of people.”

Even the compliments for Kerouac are double-edged. He is admired for his historical place, but just bring up his style and people will laugh. Many professors and critics find his writing naive: plotless and pointless. They degrade his work as easy, flowing from the hands of a madman who never revised or even cared about grammar.

Many critics and writers compliment Kerouac for being the leader of the Beat Generation, which Amram finds preposterous. For Amram, the Beat Generation never existed. He hates when people ask him how it felt to be a member of the Beat Generation. It was solely the creation of a marketing machine. “'On the Road' [the movie] will help to dispel a lot of dumb stereotypes,” he says. “And you can say goodbye, Beat Generation and beatniks. Hello, Jack Kerouac.”

Amram hopes that Kerouac’s name will one day be disassociated with the Beat Generation in order for people to just look at his work for what it is: great storytelling. And this is exactly what needs to happen for critics and writers to stop dismissing his craft. Kerouac needs to be freed from his label. Amram says, “The reason why people love him all over the world and in all the different languages has nothing to do with fashion. Nothing to do with Beat. Nothing to do with some movement. It has to do with excellence in telling a story that rings true with people’s lives.”

While other literary figures are championed for breaking free of traditional narrative form, Jack Kerouac is still ridiculed for lacking plot, shape and form. He’s attacked for his novels being so free flowing and “improvised,” and he’s still judged by conventional thought. It seems important that not only should Kerouac be freed from the Beat label, which he despised, but also from the conventions and expectations of the novel.

Imagine for a moment if "On the Road" were published today — as a memoir. Would his book have been received differently? Probably. Memoirs are allowed many concessions in terms of structure and dramatic intensity compared to novels. Most readers of memoir aren’t expecting an Aristotelian plot with a perfectly timed recognition and an earth-shattering reversal. "On the Road" may have been judged unfairly because it was ahead of its time — or part of another time altogether.

“If the playwright, composer, author, doesn’t stay in the prison cell they’re assigned by people who can’t do it themselves,” Amram says “they’ve committed a criminal act and should be put in solitary confinement until they learn to behave themselves. It’s an extension of the penal system. They put creative people into that penitentiary. Fortunately, when you read their works, they are then freed from that penitentiary.”

In the New York Public Library, there are several versions of "On the Road," some under different titles, which prove Kerouac actually drafted. The idea that he didn’t revise is not altogether accurate. A better way to look at Kerouac’s process is by comparing it to a painter, someone like Van Gogh. A writer who made numerous sketches, paintings, drafts of the same scene or story, until in one glorious excursion into the unconscious, the work just clicked. To truly appreciate Kerouac’s style, readers and critics should move beyond comparisons to other writers and move even outside of the medium, by comparing his dashes, blips, deletions of words as a way to create a visual representation of a voice, a song, a melody line that Kerouac heard bopping in his head. And this is an idea many Kerouac fans recognize — the dashes are longer rests, the punctuation a manipulation of time and breath … notation.

Of course, there are a number of readers who admire Kerouac for his craft, but it seems to me Kerouac’s work is still received with impassioned polarity. At the same time, there also seems to be a growing number of readers who loved and read Kerouac when they were younger, designating it as a book of youth, like "Catcher in the Rye" and "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn," only to dismiss Kerouac’s work as childish in adulthood, saying they desire something with more plot, more structure, more depth. I spoke with Joe Clifford, the author of "Choice Cuts," who said that he could no longer reread Kerouac — though he loved reading his books when he was younger — because they reminded him that he’s an adult, that his youthful road trips are replaced by manhood and reveal a heartbreaking memory of a past.

“I think one reason people don’t admire him as much for his style as they get older is because it is so fucking naive,” says Wakefield. “On the road, going across the country. O Kansas City. O St. Louis. O the great American night.”

Even today, Kerouac is still not being read with a clear vision. Perhaps some readers never took to or went back on the road — due to fear or family — and therefore can no longer revisit his work. Perhaps it’s hard to even look at his writing, because back through the book, readers are actually looking at themselves. And it’s easier to say, well, Kerouac’s naive, he lacks structure and plot, than to say I missed out on something. Maybe some readers have given up on the search for beauty and spirituality, or they’re not one of those people who “burn burn burn like fabulous yellow roman candles,” and that knowledge is painful. If writers and critics who dismiss Kerouac for his craft — often without reading his books — are honest with themselves, they will see that they still haven’t examined his work beyond the packaging.

Shares