I woke up shivering, my head rattling against the window of Kevin Walsh's old Ford Maverick. It was 1:30 in the morning, 33 Thanksgivings ago, and we were on the road near the Hoover Dam, bound for a reunion with friends in Chico, Calif.

I pulled my lumpy down coat tight against me in the frigid car. The heater was broken, Kevin had insisted when we left Flagstaff the night before; there was simply no point in testing it.

I looked over at his bony hand gripping the wheel, knuckles white. The other stroked a goatee to a sharp point below the chin. Kevin sat ramrod straight, glaring out at the road, his right eye narrowed ferociously.

Suddenly I was wide awake, feigning nonchalance.

“You okay, Thunderbolt?” I asked him, calling him by his stage name.

“Fine, Ace,” he replied sharply. That was my nickname back then. “Really just fine. Now why don’t you go back to sleep?”

His grip tightened. The radio crackled from a distant storm.

* * * * *

A few days earlier I’d gotten a call my friend John Zarske, like Kevin a bluegrass and folk musician. I’d recently moved to New York from Flagstaff, and was in my first semester at NYU.

“Something’s wrong,” Zarske told me. Kevin had been going into friends' houses when they weren’t home, rearranging their furniture or changing into their clothes. He said he’d discovered a global conspiracy to silence the truth. A brain-deadening gas flowed in the ventilation system of every school in America. The CIA was involved, tapping all the phones and arranging spy satellites to penetrate the interiors of school children's desks. Kevin told Zarske that I’d found out about this; that’s why I’d moved to New York.

Come on, the Thunderbolt was probably just stressed out, I told Zarske. He just needed a dear friend by his side, someone who really understood him. Me, in other words. I’d take a detour to Flagstaff, delaying my Thanksgiving trip to California, and a reunion with my girlfriend, in order to talk sense into Kevin; perhaps I’d even invite him to join us in Chico.

The arrogance of my optimism soon met the hard chill in Kevin’s eyes. “So they got to you too, eh, Ace?” he asked when I insisted there was no conspiracy. I felt cold in my body; within seconds his recognition had turned to contempt. “You need help,” I pleaded. He was having none of it. Now, I was part of the problem, an enemy in the making.

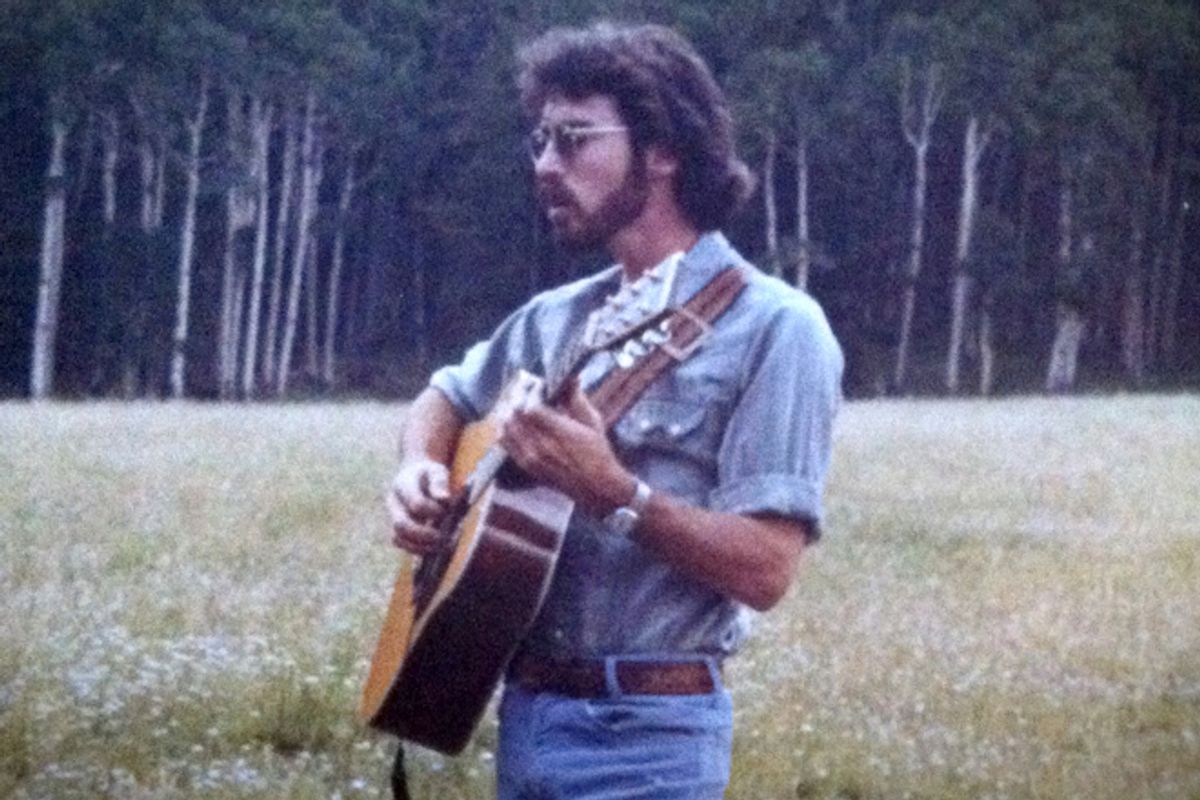

I tried to go deeper, evoking the touchstones of our friendship: drinking Jim Beam in front of the fire in my old A-frame in Mountainaire; splitting aspen and juniper logs in Hart Prairie in late fall; figuring out how to rebuild the engine of an old Pontiac Tempest I’d named Ray; how we all sang along as Maestro Kevin, with the devilish grin that pierced his coke-bottle glasses, hunched over his Martin, madly strumming Django Reinhardt. I believed that memories, friendship and love could be a salve for whatever haunted my friend. But nothing reached Kevin; with each story, he shook his head, disgusted in me.

Why had I assumed that madness could be met with reason? Perhaps because I was 23, and still attached to the wild feeling of freedom, of unlimited possibility.

I felt a panic, as if solid ground had vanished. Now the savior was vanquished; now he wanted to escape. I told Kevin he was too ill to travel. “Sure, Ace,” he said. And if I tried to go to Chico without him, he’d find us all there eventually; the scene, he promised, would be ugly.

* * * * *

At dawn fingers of warm air drifted out from the dashboard vents. There was nothing wrong with the heater. Kevin was still at the wheel, his hair brushed back, face placid and clear. “How’d you sleep, Ace?” As if nothing had happened.

He touched his throat, then cupped his hand over his left ear.

Way dowwww-nnn in the Blue Ridge Mountains

Way down where the tall pines grow-ohh

Lives my sweetheart of the mountai-innnns

She’s my little Georgia rose

* * * * *

In the early light of Thanksgiving, we sang our way into central California – channeling the David Bromberg, Ian Tyson, Seldom Scene and Antonio Carlos Jobim that Thunderbolt Kevin Walsh sang onstage. He wasn’t a fast picker; sometimes his voice was off-key; but no one could hold a room better than the Thunderbolt. In the Flagstaff clubs, he had us cupped in his hands: on his gleeful urging, we’d snap our fingers, howl at an unseen moon, bang our breadsticks together, turning them into crumbs.

We came upon a farmstand on a lonely two-lane road. Chico lay an hour north. The counter was covered in baskets of gourds, kiwi fruit and small pumpkins. “Prices are marked. Please put the money in the change box. We’ve gone to church. Happy Thanksgiving.”

Kevin’s eyes shone bright and wet. “There are still good people,” he whispered, astonished at such an act of trust. We left coins in exchange for some small knobby gourds. They would look good in a straw basket on the dinner table.

* * * * *

The weekend was a disaster. Kevin’s paranoia and disconnection deepened; he delighted in peeing on my girlfriend’s tires, and threatening to stab a knife into them. “Thus spoke Sarahwhoseit,” he kept saying, twisting her name while evoking Nietzsche. Meantime our entourage had imbibed so many other substances, many were no longer hungry. When the dinner came, few of us ate. As I recall, however, the Thunderbolt dined heartily.

Eventually, he took to wearing our host’s clothes, climbing his fruit trees and hooting like a monkey. By this time I was back in New York, having failed again to connect reason to the quicksand of madness, and get him in the Maverick for the drive back to Arizona. His father and brother came from Phoenix to bring him home. They coaxed him out of the branches and finally into years of drugs and treatment for paranoid schizophrenia. The disease, I would learn, often emerged in intelligent, creative people in their 20s.

My relationship with Kevin had fundamentally changed. I was 2,000 miles away, confused and uncertain how to respond. And busy, too, I reasoned; a crusading journalist in the making. I withdrew from inquiry about his health, diving into my studies and sharpening my ambitions. I lost touch. Perhaps I doubted that a friend who had disappeared into a haze of sickness, and with him the wildness and possibility of young men in youth, would ever return. I also didn’t know how to be friends with someone so unwell, and didn’t have the strength to risk one more contemptuous gaze from someone so dear who looks right through you, as if you don’t exist.

* * * * *

Two decades later, I heard from Kevin. He’d pulled his life together, he reported, and was working in mental health administration in Humboldt County, Calif. As it happened, I had an assignment in the timber country up there.

We met for dinner. On his mind was his new life: careful, controlled, a little boring perhaps. Safe, it seemed. We allowed the past to trickle in: hikes on the saddle of the Peaks, in the Arizona high country; a bass player we knew, now teaching Spanish; the breadsticks at the Spaghetti Station. His manner was contemplative and slow, with little of the verve and fire I’d known. The edges had been dulled and softened; the paranoid anger gone, or buried. I thought it was the lithium. Whatever: Something was settled; something was lost. But he’d recorded a new CD, “Two Tunes From T-Bolt’s Tunery.” With a sad smile, he passed it to me across the dinner table. The tunes: “Hope 1996” and “Lockdown,” which he called “my dedication to the medication.”

That was the last time I saw Kevin.

* * * * *

On election night I got a call from my old friend Ed, owner of the Flagstaff restaurant where Thunderbolt often took the stage. The Phoenix paper had run an obituary. Had I heard anything about the death of a Kevin Walsh, 57, of Flagstaff, Ariz.? No, I hadn’t. Did he have a lot of brothers? Ed asked. Yes, he did.

I went online and found a remembrance from a mutual friend:

Thunderbolt, my dear friend and brother, wrote Craig Yarbrough. I am saddened and shocked to hear that there will be no more music and laughter coming from you.

Yes, it was the same Kevin.

Kevin had drifted back to Arizona, alternating between well and unwell, on and off his meds, on and off the street. Sometimes you’d hear a report of him sleeping in a doughnut shop; other times, he had a good gig playing the Grand Canyon. That’s where he belonged, onstage in northern Arizona, and where he remains most in my mind: Sitting back on his stool, taking his hands off his guitar to tell a story, fingering his goatee, throwing his head back and laughing, then launching into Jobim.

So close your eyes

For that’s a lovely way to be

Aware of things your heart alone was meant to see

The fundamental loneliness goes whenever two can dream a dream together.

Thank you, Thunderbolt. Happy Thanksgiving. I’m grateful for your friendship.

Shares