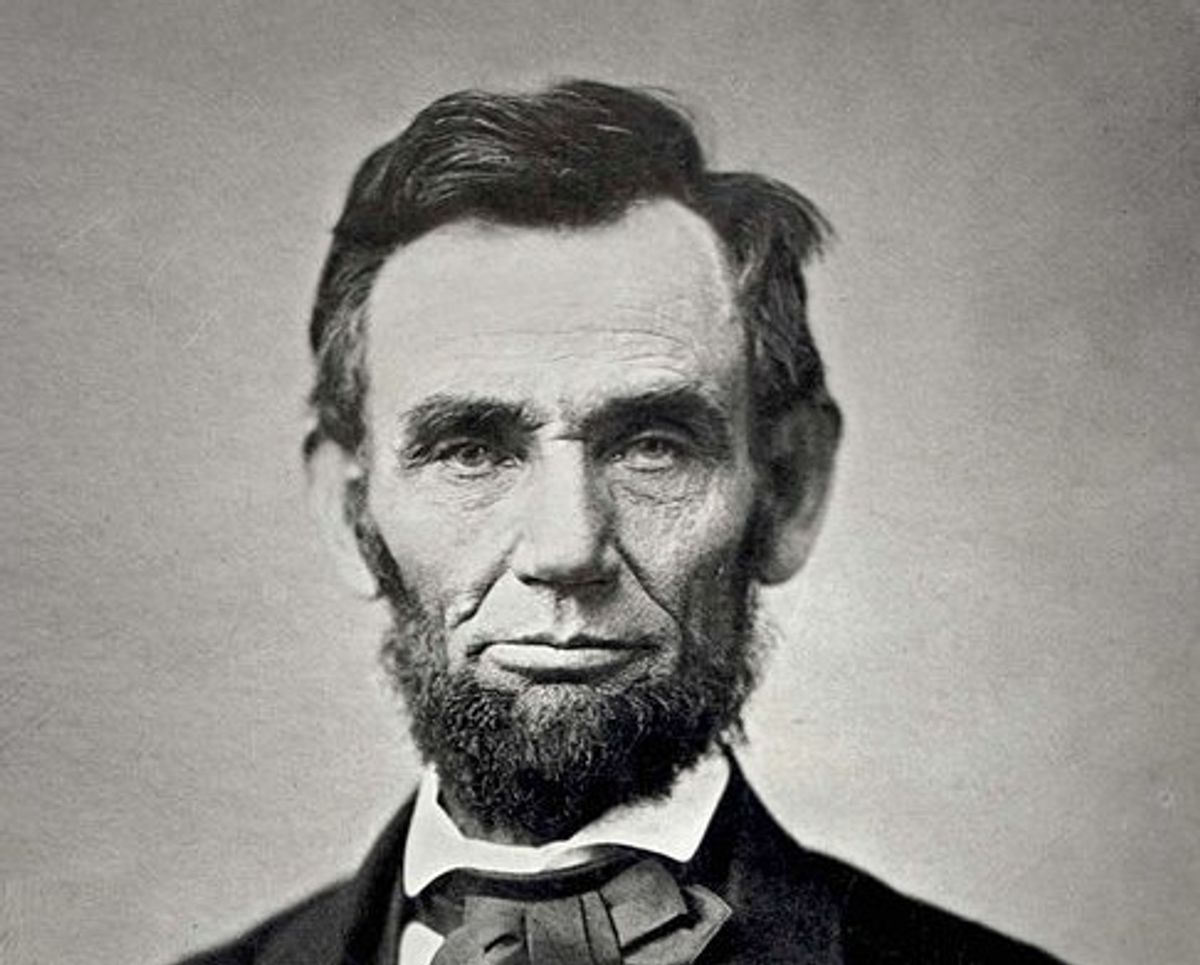

Over this Thanksgiving week, you may find yourself in a movie theater watching Steven Spielberg’s treatment of Abraham Lincoln and the battle to pass the 13th Amerndment, which abolished slavery once and for all. There’s much to be said for Lincoln [3]: marvelous acting, less mythologizing than usual, and a fascinating window into raucous realpolitik. Spielberg’s film stands several cuts above any movie depiction of the Lincoln presidency you’re likely to see.

Over this Thanksgiving week, you may find yourself in a movie theater watching Steven Spielberg’s treatment of Abraham Lincoln and the battle to pass the 13th Amerndment, which abolished slavery once and for all. There’s much to be said for Lincoln [3]: marvelous acting, less mythologizing than usual, and a fascinating window into raucous realpolitik. Spielberg’s film stands several cuts above any movie depiction of the Lincoln presidency you’re likely to see.

Lincoln himself stands several cuts above the vast majority of U.S. presidents. After some equivocating, he freed the slaves, a monumental undertaking that was a service to the country and to humanity in general. He was also friendlier to workers than most presidents, an affinity noted by Karl Marx, who exchanged letters with Lincoln leading up to and during the Civil War. (You won’t see the GOP acknowledging that!)

But there’s a side of Lincoln that no Hollywood film shows clearly: He was extremely close to the railway barons, the most powerful corporate titans of the era.

Liberals are fond of referring to Lincoln's concern about corporate power, summed up in a letter [4] he wrote to Col. William F. Elkins in November 1864:

"I see in the near future a crisis approaching that unnerves me and causes me to tremble for the safety of my country....corporations have been enthroned and an era of corruption in high places will follow, and the money power of the country will endeavor to prolong its reign by working upon the prejudices of the people until all wealth is aggregated in a few hands and the Republic is destroyed."

Lincoln’s observation is prescient. But here’s the inconvenient truth: Some of the most powerful corporations of his time were wildly enriched by having a friend in one Abraham Lincoln.

This friendship goes back to Lincoln’s early days as a scrappy young lawyer. After being admitted to the bar in 1827, he hopped around and finally landed in Springfield, Illinois in the law practice of William H. Herndon in 1844. Like any young lawyer, he had to hustle to handle enough cases to live comfortably. And, like most young lawyers, he went where the money was. And the money was in the burgeoning railroad industry.

In 1851, Lincoln tried his first major railroad case, representing the Alton & Sangamon Railroad before the Illinois Supreme Court. The defendant had bought stock on the belief that railroad lines would run near his home and give his property value a boost. Unfortunately for him, the Illinois legislature subsequently amended the company’s charter and changed the route so that it no longer ran near his land. The defendant refused further payments to the railroad company, arguing that the original contract was altered and thus nullified.

Lincoln argued otherwise, and convinced the Supreme Court. His victory was a big deal and set a precedent that was evoked throughout the rest of the century. The railroad industry was deeply impressed. Lincoln’s career as a railroad lawyer took off.

Through Lincoln’s skilled legal arguments, the railroad barons increased their wealth and a lot of others got the short end of the stick. Land owners were sharply limited in the compensation they could receive when a right-of-way was granted over their property for a railroad line. As historian James W. Ely Jr. has documented, Lincoln proposed that the supposed “offsetting benefits” of such lines could be held against claims of damages. In other words, a farmer could be told that he would benefit from the railroad line, and was therefore entitled to less compensation when a track ran across his field. This assumed benefit was highly speculative. Often estimates turned out to be way off-base. The offsetting-of-benefits argument was held by many to be grossly unfair and became deeply unpopular. But it was great for the railroad barons, and sparked increased railroad development.

Lincoln also argued in court that farmers and ranchers would have to bear the expense of building fences so that their animals did not wander onto train tracks. Through his carefully prepared cases, railroad companies got windfall tax exemptions that many felt constituted favoritism and unfairly burdened other taxpayers. Through his prowess, railroads won the right to limit liability for damage to cattle and other animals caused by delay in transit.

Lincoln first appeared for the Illinois Central Railroad, probably the largest business corporation in the state, in May 1853. He was handsomely rewarded for his successful advocacy for the company. By October of that year, Illinois Central placed him on retainer and gave him the special bonus of a free annual pass on the line.

It’s important to point out that despite Lincoln’s commitment to the railroad industry, he also handled suits against the carriers. Ely reminds us that lawyers in those days couldn’t afford to take only cases on one side. So whatever his philosophical leanings, Lincoln went for the cases that would support his practice. This plays out in his handling of cases related to slavery. Though Lincoln was a lifelong opponent of slavery, he would represent the interests of slave owners, such as runaway recovery, when he was paid to do so.

Lincoln was also a Whig, and as such, railroads were a key part of his vision for economic growth. As an Illinois legislator, Lincoln threw his support behind state subsidies for internal improvements and voted for several railroad charters. Like many other Whigs, he believed that railroad expansion would bring enormous economic and social benefit to the country.

During the late 1850s, Lincoln collected more fees from Illinois Central Railroad than from any other single client, and he was closely associated with Illinois Central until his election to the presidency. Just before his nomination for president in May 1860, Lincoln won a big tax case for his main client, Illinois Central.

Lincoln was elected president on a platform that declared [5]: “That a railroad to the Pacific ocean is imperatively demanded by the interests of the whole country; that the Federal Government ought to render immediate and efficient aid in its construction.” President Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act of 1862 and the 1864 amendments to that act. He was clearly a major railroad booster in the political world.

The relationship between corporate interests like the railroad industry and slavery was complex. Political scientist Thomas Ferguson has observed that some of the railway tycoons genuinely disliked slavery, and their support for Lincoln had an element of moral and philosophical conviction. But for most, the bottom line was the bottom line. They needed an advocate who could help them expand a profitable industry westward, and Lincoln was their man. In his essay “Beyond Their Means? The Costs of Democracy From Jefferson to Lincoln[6],” Ferguson writes:

“There is no doubt about the deep involvement of railroads and allied business interests in the Lincoln candidacy from its earliest days. Nor is there any question that the lawyer who made a famous argument on behalf of the rights of railroads to build bridges anywhere won the nomination by garnering crucial support from iron manufacturers, coal mining interests, and other firms intent upon tariffs, land grants, and other national developmental measures.”

The railroad industry connected the country and did indeed bring many benefits. No longer did every community have to be self-sufficient. The materials needed to build the railroads boosted other industries, like iron and steel.

But there’s a reason the railroads feature so prominently in the ever-popular board game Monopoly (which you might break out during the holidays). The railroads were America’s first big business. The industry led to the growth of Wall Street, which needed to handle the enormous amounts of capital required to build and operate the lines. As they grew more powerful, the railroad companies began to squeeze out competitors and charge outrageous prices. Farmers were held hostage to railways that refused to move their goods unless they paid what was demanded. Because of their wealth, railroad barons could afford to buy and rent politicians in Washington.

Nineteenth- and early 20th-century cartoonists depicted the monopoly threat in the form of a gigantic octopus, its tentacles reaching into every nook and cranny of the country. America, for a long time, was held in a stranglehold by the railroad monopoly.

*For more on Lincoln’s railroad advocacy, see James W. Ely Jr.’s "Abraham Lincoln as a Railroad Attorney".

Shares