Indeed. One of the few benefits of anxiety is the creation of fictional worlds or alarming perspectives wherein writers can indulge and play out their fears. This may heal, it may exacerbate, I’m not sure. Nevertheless, a writer’s worries, which come in many flavours, are a boon to readers with similar tastes.

Your first choice is Wolf Solent by John Cowper Powys. What’s the flavour of worry here?

Powys was one of 11, several of whom also published, and was an extremely sensitive soul. He was born in the 1870s, which meant he suffered the shocks of a new noisy century when he was old enough to worry properly. His medium was more existential angst and self-doubt, offering an antithesis to Whitman’s universe-embracing enthusiasm. Powys started out teaching at girls’ schools in England, which he somehow parlayed into an ongoing gig on the American lecture circuit, where he spent his middle years. He had a wife and child in England and a common-law wife in the US. His autobiography doesn’t mention either of these women, and just barely, his mother. He was an anti-vivisectionist and a vegetarian. He enjoyed long walks and mistrusted airplanes. Depending on whom you ask, he was a notable footnote to 20th-century literature or an overlooked genius.

And the book?

So our hero, Wolf Solent, is, coincidentally, an extremely sensitive soul, alive to every blade of grass and housefly, and he suffers for it. He’s in his 30s when he returns from teaching in London to work in the small town of his youth, where his deceased, free-loving father had disgraced the family by having an affair. He is coming to a presumably serene writing assignment for the local squire, to escape the intensity of the city, to understand his past, and to somehow vindicate his tightly wound mother. Nothing goes to plan. A battle between his father’s joie de vivre and his mother’s nervousness rages in his head. He becomes sympathetic to his father’s mistress, becomes attracted to his half-sister. The job he’s come for is not at all what he’s expected. In fact, nothing in this town provides relief from intensity. There are many contemplative walks through the English countryside where he plays out every reading of his life in order to make some sense of it. His reverence and concern for the natural world is laudable and, admittedly, hard-going in places. Powys hated most things modern – such as, say, technology and capitalism – so he lingers where others might move along.

Wolf falls for the local tombstone carver’s daughter, but even this isn’t a totally healthy plot. Part of his attraction to her hinges on his hearing about a photo of her straddling a headstone. Her name is Gerda. You could read the book just for the delight of the names.

Why do you love it?

For an adult, Wolf has epiphanies with the frequency of a 15-year-old, which leaves him perpetually resolute and perpetually changing his mind. His constant revelations of nature’s bounty and his miserable doubts of reality itself run in counterpoint to the actual events of the book. Read the first chapter for the feel of things. It traces his thread of exultation and despair as he sits quietly in a train on his way out of London. There’s another marvellous chapter where Wolf and Gerda court each other with zeal and only the reader can hear how poorly they understand each other. This manic perspective feels at odds with all the pastoral indulgences, but it makes the book a unique record of the literary moment of the late 20s.

Your next book is Stefan Zweig’s Beware of Pity.

I generally object to a title being such a fortune cookie, but Beware of Pity works somehow. Zweig was an Austrian Jew, born in the 1870s, a pacifist, who fled Austria in 1934 and later he and his wife killed themselves because of Europe’s prospects in 1942. His concerns were quite real and moral.

What’s the story?

Just before the First World War, Hofmiller, a young Austrian officer from a modest background, finds himself stationed in a town where he knows few people. He scores an invitation to the home of the richest local family and, at the end of the evening, realises he has not spent time with their attractive daughter, Edith. He invites her to dance, but realises – to everyone’s horror – that she is sitting in a wheelchair and can’t even stand. The worst faux pas imaginable, and he flees. But he is given another chance, which he eagerly accepts. To be nice he starts spending more and more time with the family, focusing on Edith, keeping her company – keeping himself company too. Relationships seem almost balanced at first. She’s sweet, if a bit over-eager for his attention. It is the father, though, who compels Hofmiller to involve himself more, to help find treatment for her condition, to lie to her about its effectiveness, to let her believe she has a chance of recovery. It’s all, of course, in the name of keeping her happy. Hofmiller’s eagerness to please, Edith’s father’s eagerness to please – beyond what is practical or real – subtly becomes a ticking bomb of anxiety. Where it naturally leads is to Hofmiller’s proposal of marriage. A good soldier, he will do everything he can. Devastation everywhere.

Where’s the fun?

It’s a tense, emotional thriller for the well-meaning. All the flickers of behaviour in this family are brought into focus; all the tiny efforts Hofmiller makes to do the right thing are understandable in their urge to appease. And it’s all so excruciatingly felt, even as the plot drums along, taking you through drawing-rooms and barracks. But it’s more than a melodrama. Beware of Pity was first published in 1938. It is an ethical story and a dark one: every good intention and social nicety leads him further from the truth and leads Edith further astray.

Do I need to outline the plot? There’s this guy Humbert, see, and he falls for this underage girl, Lolita. He knows it’s not OK, but that doesn’t slow him down. Hence, the worry, here in the form of obsession. He flirts with the girl’s mother just so he can linger in her tender young presence. Then, when the mother gets conveniently run over, he drives the girl around the US, pretending to be her father, so they can share motel rooms as they go. She gets away and marries and he chases her around the US some more. It’s all because of some unresolved issue he had with a childhood sweetheart that blossomed into a feverish sort of paedophaelia, as if that’s an excuse. His desire to manipulate her never stops and, maybe because his efforts are not all that successful, you stay with him even as his creepy hand inches ever further up her thigh.

(Lolita’s motivations, her actions, and her ability to survive are another thing entirely. In fact, this might be an area for a grand feminist work, in the vein of Rhys’s The Wide Sargasso Sea. Who wouldn’t read the book called Humbert? Would it be speared through by anxiety, though? I don’t think so.)

Why does this book make it on to so many lists?

What’s spectacular for me is the triumph of the humour over his loathsomeness. You can almost sympathise with his compulsive stream of thought, and if you can’t, you can at least admit to being entertained. Nabokov’s wry reading of America and of Humbert manages to overcome much of what’s repellent in the book. (For me, not my professor friend.)

Your next choice is The White Album by Joan Didion. A female, congratulations.

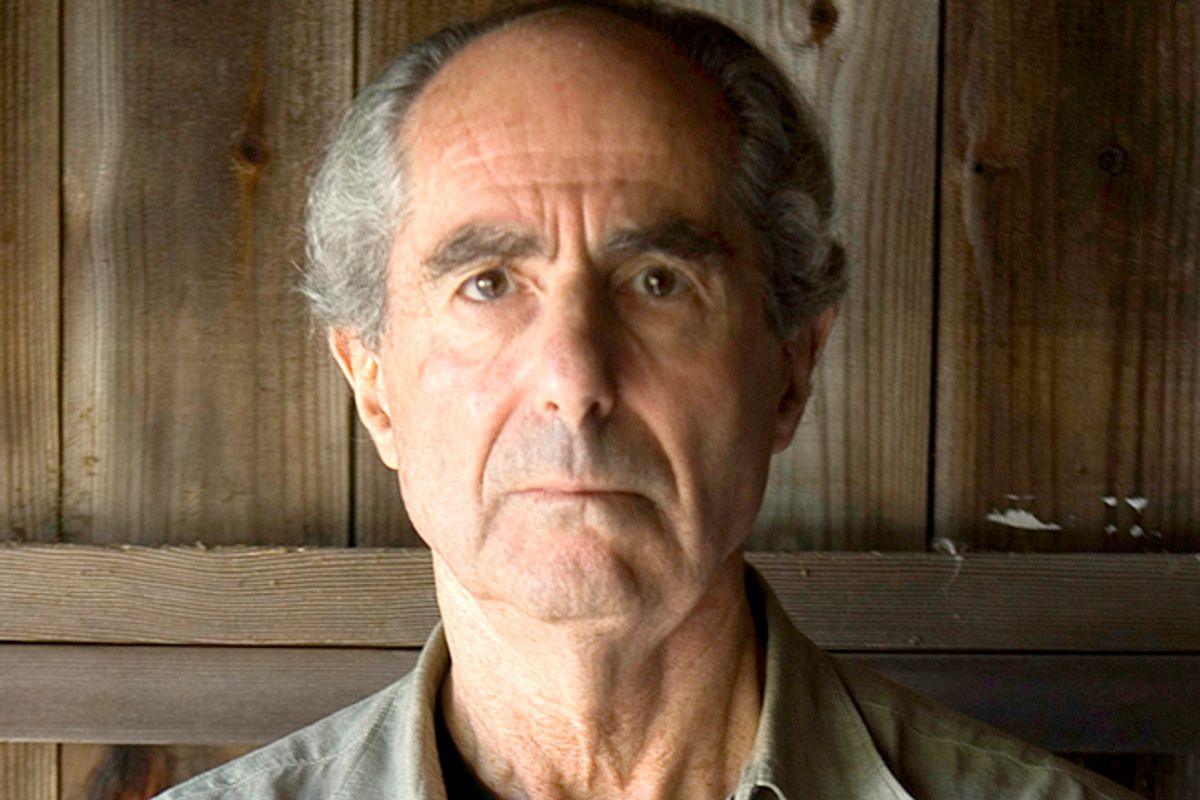

My list is still bright white and western, but yes, thank you. I originally had Philip Roth’s Letting Go here, in the social anxiety and neurosis corner, but my stack of Didion made me wonder if non-fiction might be allowed, which would at least address the gender gap.

Spin The White Album.

With her gaze on California of the late 60s and early 70s, Didion gives us the Black Panthers, Janis Joplin, Nancy Reagan, and the Manson follower Linda Kasabian. She also gives us her psychiatric report, her migraines, her diagnosis with multiple sclerosis. There are many good profiles in here (a whole section on women, in fact) but she has her nervous areas of attention. From her famous opening line – ‘We tell ourselves stories in order to live’ – onwards, she makes a persuasive case for the notion that we are fooling ourselves by seeking too much narrative in reality. Chaos reigns in these pages and she seems to relish the telling detail that proves it: Nancy Reagan’s cameraman telling her to fake picking a flower for the camera; the boys who majored in shop in high school, worked in gas stations and later held them up; an acquaintance from her time in Berkeley who tried to kill himself in Mexico, survived, and returned home to join the Bank of America’s three-year training program for executives. Wonderful, awful details that paint a portrait.

Didion is a joy to read, it’s true.

She had the journalist’s access to many, many people. The book could have been anything, from celebrity worship to offbeat cool, but her deadpan observations and her staccato organisation of the facts manage to cut in between. As a distillation of the moment, it works like the movie Nashville: critically observant, fabulously detached and just a bit mesmerised and horrified by the chaos.

The Plot Against America by Philip Roth. Are we in the realm of paranoia?

Yes, one of the classic worries. It is more usual for the speculative to inhabit the future and meditate on all that could go wrong, but Roth goes back in time. What if Charles Lindbergh won the presidency in 1940? He didn’t have much political experience, but, hey, he was a celebrity. He could fly a plane and Roosevelt couldn’t walk. It’s not outside of the realm. What follows, politically, is utterly believable. Rather than dive into World War II, Lindbergh goes isolationist (as only an able-bodied man could). He allies the US with Germany and Japan. Yes, it’s still America, but increasingly, more fascist, more anti-Semitic.

The best way to tell stories of horrific times is not through the central players amassing power, but through the lives of the people off to the side, simply trying to survive. In The Plot Against America, it’s a Jewish family from New Jersey, who happens to be the Roths, and the story is told by Philip, aged seven. The family is distressed by Lindbergh’s nomination to the Republican ticket, but it isn’t till later, after his election, that their worst nightmares get teeth. It happens during that perfectly innocuous American tradition, the family trip to Washington DC. Their hotel reservation has disappeared. A simple enough error, but we know that it’s not an error, and we know that it’s only the beginning.

Why the love?

The book stuns through its complete plausibility from a historical angle and the prism of the seven-year-old’s youthful but (unsurprisingly) intelligent perspective. Years after reading it, the broad sweep of the book lingers in my mind as a cautionary tale, as if this was some almost-true alley of history we narrowly avoided.

And retrospective speculation doesn’t normally have the force that The Plot Against America has. What gives the book its immediacy are the parallels with War on Terror mindset taking hold in the beginning of the last decade. The justifications for clamping down, for profiling, for marginalising suspect groups are all there and all well worth worrying about.

Shares