Remember the perceptual illusion where you look at a picture and you’re certain that you see the bust of a young woman? Then, if someone draws your attention to certain details, suddenly the picture transforms into the profile of an old woman. It’s a disorienting trick. You think you know what you’re seeing, but then you aren’t so sure.

Remember the perceptual illusion where you look at a picture and you’re certain that you see the bust of a young woman? Then, if someone draws your attention to certain details, suddenly the picture transforms into the profile of an old woman. It’s a disorienting trick. You think you know what you’re seeing, but then you aren’t so sure.

The Jeffrey MacDonald murder case is one of the most disturbing in living memory. There are only two possible pictures, both nightmares.

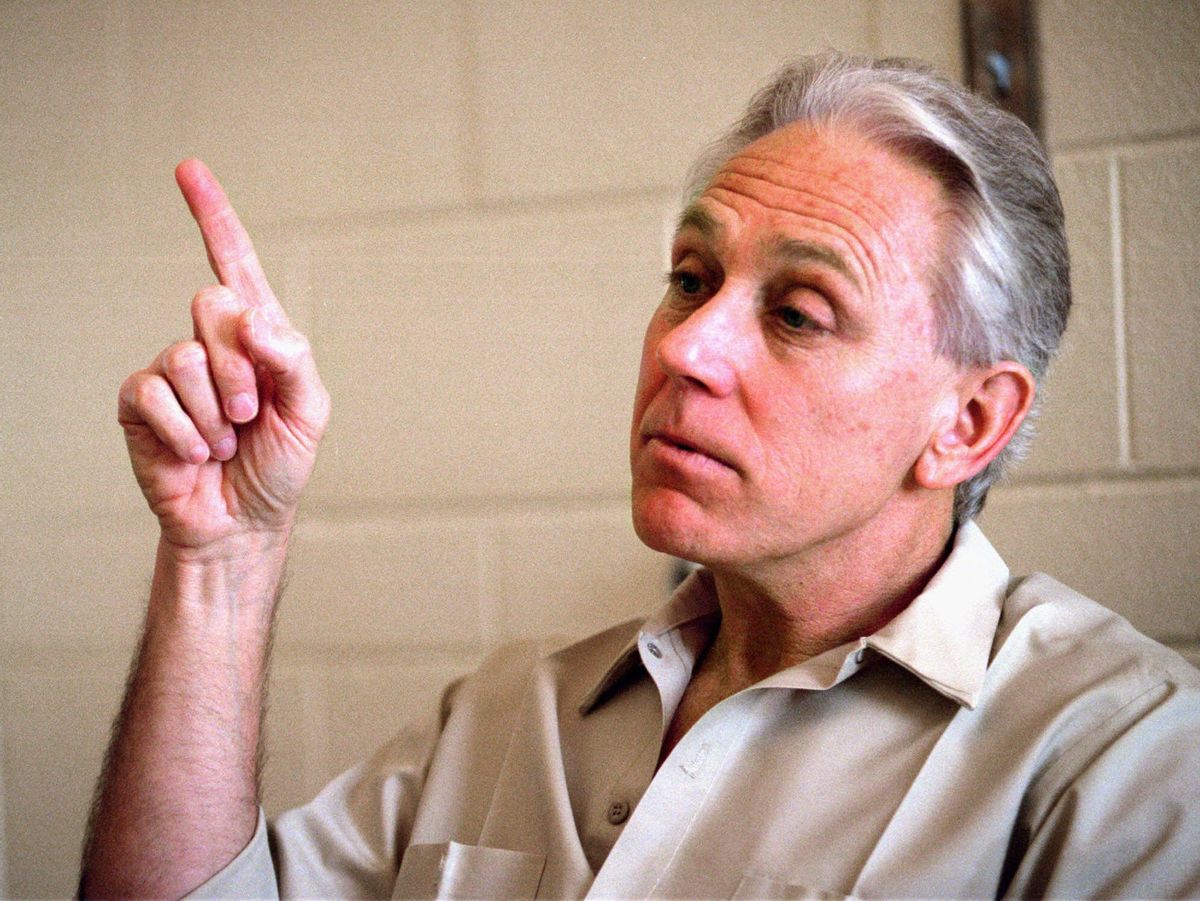

Picture No. 1. Jeffrey MacDonald, a Princeton-educated Green Beret doctor with no history of violence and a sterling record, butchered his pregnant wife and two young daughters using a knife, ice pick and club. Then he injured himself and set up the scene to make the crimes appear to be the work of intruders. He claimed they chanted, “Kill the pigs! ... Acid is groovy!” and scrawled the word “PIG” on the wall in his wife’s blood.

Picture No. 2. Jeffrey MacDonald, a bright young man with everything in life to look forward to, lost his wife and children to senseless, horrific violence. A military hearing found charges against him “untrue,” but he was convicted nine years later in a civilian trial. He has been imprisoned for three decades for a crime he did not commit.

Two possibilities: MacDonald is a monster, or he is a victim of terrible injustice. Young woman; old woman.

Until recently, most people saw Picture No. 1. So did I. I grew up in Raleigh, N.C., about an hour from the Fort Bragg army base in Fayetteville where the murders occurred on Feb. 17, 1970, in the middle of the night. I was born in May of that year, and would thus be the same age as the child Colette MacDonald was carrying when her life was snuffed out. In the early '80s, I whipped through a dog-eared copy of "Fatal Vision," Joe McGinniss’ sensational true-crime novel about the killings. It was almost as scary as "Helter Skelter" – the story of the Charles Manson murders in California that are said to have inspired Jeffrey MacDonald in the coverup for his homicidal rampage.

In 1984 I was glued to the TV, like millions of other Americans, watching the popular miniseries based on McGinniss’ book. McGinniss made the murders sound like the work of a diabolical genius, a man who could transform in a moment from a loving father to a homicidal maniac, and again, in the blink of an eye, to a calculating con man. I thought of devils that lurked in human flesh, like in "The Exorcist," another popular based-on-a true-story-book-turned-movie of the period that floated around our house. When the show was over, I retired to the safety of my bed, safe from unpredictable evils.

A Shifting Picture

McGinniss’ stark rendering of Picture No. 1 stuck in my mind until recently when a friend from North Carolina told me that Errol Morris had published a book suggesting MacDonald was innocent. That got my attention: the Oscar-winning Morris, whose film "The Thin Blue Line" exonerated a Texas man wrongfully convicted for murder, is one of the world’s great documentary filmmakers. He is both a careful researcher and a profound investigator of the human condition.

My friend and I sat around in her backyard, tossing up what facts about the case we could recall. I even laughed at the idea of hippie murderers in North Carolina. Of all places! But then I felt uneasy. “You sure Errol Morris wrote the book?” She was sure.

Soon I was reading Morris’ "A Wilderness of Error," feeling skeptical and wondering why this reputable man would involve himself in a case that everyone and their mother (including mine) knew the truth about.

But it didn’t take long to realize that something was wrong. Enough somethings to fill the long, solitary chapters of a man’s life unfolding behind prison walls.

Morris researched the MacDonald case for 20 years and knows each labyrinthine turn of its progress through the criminal justice system. Even before bureaucratic stalling and federal machinery overtook the search for truth, things were working against Jeffrey MacDonald. A crime scene was left open to bystander traffic. Inexperienced military police failed to pick up a woman near the house who fit MacDonald’s description. Many think this woman could have been Helena Stoeckley, a drug abuser and professed member of a witchcraft cult who repeatedly confessed to having been at the MacDonald house the night of the murders, but recanted her story whenever she seemed to fear prosecution. Now deceased, she remains a pivotal figure in the case.

As I read Morris’ meticulous examination the evidence, the picture in my mind became less clear. I began to see that Joe McGinniss’ creation of Picture No. 1 might be just that: a creation. Some of the “facts” I thought I knew began to look more like ideas conjured by eager prosecutors and a journalist who had dealt so disingenuously with Jeffrey MacDonald in writing "Fatal Vision" that he was sued after publication. McGinniss' publisher settled with MacDonald out of court, after the judge called the author a “con man.” (This story, in its own right, became a famous book about journalistic ethics by Janet Malcolm.)

The story many of us think we know tells that MacDonald's wounds were superficial. But he had multiple bruises and puncture wounds, and two stab wounds, including one that collapsed his lung -- a serious injury that left him falling in and out of consciousness. The popular story says there was no evidence of intruders. But there was, including wax drippings (MacDonald insisted that one of the intruders carried a candle), fibers and hairs that did not belong to the household or family members.

McGinniss drew on pop-sociology to render an image of a psychopathic killer in the guise of the friendly doctor-next-door; the kind we know from endless horror movies. He theorized that diet pills caused MacDonald to fly into a fit of rage. McGinniss had to be creative, because the man’s character never fit the crime. MacDonald had no history of violence or temper. When the initial military hearing was conducted in 1970, no one in his life could be found who had a bad thing to say about him. Psychiatric professionals on both sides pronounced him incapable of having committed the crimes. On the evening of the murders, Jeffrey MacDonald had taken his kids to ride the pony he had bought them, fed them dinner while their mother took a night class, and put them to bed. It didn’t make sense.

But did hippie intruders make sense? Maybe more than I would have thought as a teen. Vietnam-era Fayetteville was not sleepy Raleigh in the 1980s. There was violence. Soldiers’ corpses arrived at Fort Bragg stuffed with heroin. In 1970 America was gripped by the horror of the Manson murders – a fact used against MacDonald because he subscribed to Esquire magazine, which had run a story about the dark side of hippie culture. The Esquire story, for all its salaciousness, touched upon real issues that plagued many communities outside of California. In Fayetteville, an Army town, strong tensions existed between Army types like Jeffrey MacDonald on one side of the war, and hippies and protesters on the other. Helena Stoeckley confessed many times that MacDonald’s willingness to turn heroin addicts in to the police infuriated local drug dealers. She knew this world, and was herself a police informant. According to her, they wanted to teach MacDonald a lesson and rough up his family the night of the killings. But things got out of hand.

In October 1970, following an investigation and hearing, the military dropped its case against MacDonald, and he was honorably discharged from the Army. He moved to California to become the director of emergency medicine at St. Mary's Medical Center in Long Beach. But an unfortunate thing happened in the following years. MacDonald’s relationship with his father-in-law, originally a staunch supporter, became strained. Freddy Kassab had inserted himself into the 1970 military hearing and made himself the center of a media circus, holding news conferences and firing off letter to members of Congress. He wanted his son-in-law to stay on the East Coast and pursue the killers. Eventually, he turned on the man he had once so ardently defended. Through his aggressive pursuit of the case, MacDonald was indicted.

MacDonald was tried in a civilian court in 1979. Many felt that his acquittal would be a cinch, but much more was to go wrong. The nine-year lag between the murders and the trial is extremely unusual; experts consider such a lag to pose a great danger of wrongful conviction. Appearances didn’t help MacDonald, either. He looked angry on the stand. Worse still, Judge Franklin Dupree seemed to have his mind made up before the trial began. Some said he should never have taken the case because his former son-in-law was the prosecutor in the original Army hearing. Dupree would not admit overwhelming psychiatric testimony in MacDonald’s favor, nor the testimony of witnesses to whom Helena Stoeckley had confessed her involvement. Bernie Segal, a long-haired Jewish lawyer from Philadelphia, took the lead in the case and managed to alienate the entire courtroom. Segal took up nearly all the time in the critical period for closing remarks and left only a few minutes for co-counsel Wade Smith, an eloquent native Carolinian who understood the jury.

One thing about this case is never in doubt no matter who’s talking: If Wade Smith had been able to lead and give his closing remarks, MacDonald would be a free man today.

The list of misfortunes goes on: exculpatory evidence withheld; possible prosecutorial misconduct; and fallible humans who twisted the MacDonald story to fit their own agendas. MacDonald was convicted twice, both in the courtroom and in the all-important court of public opinion, which was sealed by McGinniss’ book and miniseries.

Since 1979, the MacDonald case has continued to trouble those who delve beneath the surface of the media narrative. The social justice movement is now involved; the Innocence Project, a prestigious nationwide network dedicated to exonerating the wrongfully convicted, has worked strenuously for MacDonald’s conviction to be overturned. In a 2011 press release, the Innocence Project stated:

Since MacDonald was convicted of the murders in 1979, considerable evidence of his innocence has come to light. Most recently, retired US Marshall Jimmy Britt came forward with information that another suspect in the case, Helena Stoeckley, admitted to the prosecutor that she was in the house on the night of MacDonald’s murder and that he treated to indict her for first degree murder if she admitted that in court. In addition, DNA testing on evidence that was recovered from the fingernails scrapings of one of the victims and a hair found under another victim did not match MacDonald. Earlier, evidence came to light that a FBI forensic examiner mislead the jury about synthetic hair evidence. MacDonald claimed the hairs were from the wig of one of the murders, but the forensic examiner incorrectly claimed they were from one of the children’s dolls.

None of this has set MacDonald free. By now, many members of the original hearing and 1979 trial are dead, including Judge Dupree. Judge James Fox, a close friend of Dupree's and quite elderly himself, has taken over and has dismissed appeals. Recently, the 4th District Court of Appeals ordered Fox to consider new evidence, and to examine all the evidence as a whole. On Sept. 17, 2012, in Wilmington, N.C., a crowd of familiar faces assembled for a new hearing. Jeffrey MacDonald, Joe McGinniss, prosecutor James Blackburn (who went to prison himself for defrauding his clients), Wade Smith and others newer to the case gathered once again to testify.

MacDonald now waits to see if the federal judge will vacate his 33-year-old conviction. He could get an answer by the end of this year.

Wade Smith rarely grants interviews. I contacted his office, and to my surprise, he was willing to talk to me. What follows is the transcript of our conversation.

Interview: The Spookiest Case Wade Smith Ever Encountered

Lynn Parramore: In all your years as a lawyer, what makes this case stand out?

Wade Smith: It’s a very spooky case. It’s a case that if you were telling scary stories around the dining room table and you had all your family gathered, people could hardly believe it. It’s a scary, spooky story that sounds made up. It has witchcraft in it. It has Helena Stoeckley, the dominant person who continues to play a remarkable role. She’s haunting this case. In the hearing we just had in Wilmington she played an important role, decades after her death. It is also a Manson-like killing. It has Charles Manson written all over it. It’s hard to imagine now, but in the late 1960s and early '70s there were spooky, weird people on acid — back then it was believable.

LP: Then why did MacDonald, the emblem of law-and-order, the Green Beret, become a suspect? Why did people in the community believe he did it?

WS: In every murder of a spouse, the remaining spouse is the No. 1 suspect and is almost always charged. Often, the spouse turns out to have committed the murder, so it’s not surprising that the case turned to McDonald. The crime scene was so messed up that you couldn’t depend on it. So MacDonald was the logical choice. And yet there are thousands of people in North Carolina who do not believe he did it.

Even back then, if you polled Fayetteville folks, you might have found that a lot of people did not believe that he did it. The military hearing found that the charges against MacDonald were not true. He was given an honorable discharge. He could have gone on with his life, and he should have. But he taunted the police. He made fun of them. He did interviews. When Victor Worheide, who was a federal prosecutor, later became interested in the case at the urging of the parents of Colette MacDonald, the case was gone.

LP: In Joe McGinniss’ book, "Fatal Vision," Freddy Kassab, MacDonald’s father-in-law, was presented as the protagonist. What do you recall of the in-laws in the trial?

WS: They were a very normal-looking mama and daddy. Nothing unique in any way. I think that one of the problems MacDonald had was that they expected him to undertake to find these killers, to go on a mission to find them. He didn’t do that. He continued to work as a doctor and moved to California. Some people would say that was the wrong thing to do. Others would say that that was a healthy thing to do. But his mother- and father-in-law did not want him to do that.

LP: Did anything new come out in the Wilmington hearing in September?

Oh, yes. Back in the 1979 trial, a lawyer named Jerry Leonard represented Helena Stoeckley. No one ever knew what it was Helena told him because of attorney-client privilege. He was the lawyer she was talking to one-on-one who had been appointed to advise her of her rights. I used to joke with him when I saw him around – “Hey Jerry, isn’t there something you want to tell us?” But he couldn’t, and he likely would have gone to his grave carrying the secret of what Helena told him had it not been for that hearing. Finally, in Wilmington, Jerry Leonard was ordered to tell what she had said to him 30 years ago. And she told him she had been there, at the MacDonald home, the night of the murders.

LP: She said that to her lawyer at the time of the 1979 trial? Thinking that he could never reveal it?

WS: Yes.

LP: One of the things that struck me in reading Errol Morris’ book was the use of the “psychopath” diagnosis in court and how problematic that is. Wherever you see the label “psychopath," you could almost substitute “monster” or “vampire” – you’re talking about an unnatural person who does not behave according to normal human rules, and with that label, you can believe anything of them. What’s your sense of this?

WS: It’s an enormous problem. Take a guy like MacDonald. He’s the guy that lives next door. The loving husband and father. You trust him. If he could have a psychotic episode and destroy his family – stab them with an ice pick and a knife 100 times, beat them with a stick, then Billy Graham could. Anybody could. That was my closing argument.

LP: The one you never got to make?

WS: Yes. I would have told the jury that it doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t make sense that this man, with no history of violence, went crazy like that. It all was intruders. I would have said to the jury: they were not there, and neither was I. They don’t know the truth any more than I do. The idea that people that were so certain who don’t know any more than I do -- I don’t believe I’ll ever understand how they could be so sure.

LP: What has this case revealed about the flaws in our judicial system?

WS: We all depend on excellent, honest detective work. And police officers knowing how to take care of a crime scene and preserve it. The walls will tell you what happened if you keep it pristine. Sometimes that doesn’t happen. That didn’t happen here. And so there are going to be cases where there is a reasonable doubt as to what actually happened. That is the way our legal system is set up. The defendant has no obligation to prove anything whatsoever. That huge standard protects us from miscarriages of justice.

LP: Judge Fox is a close friend of Judge Dupree, who presided over the 1979 trial. Is it possible that Jeffrey MacDonald will get justice under these circumstances?

I thought the world of Judge Dupree. He was a true gentleman, even though there were things in the trial and there were decisions he made that I disagree with. Judge Fox is also a good man. I’ve had many cases in court. I don’t know what the odds are. But I’m an optimist generally about our system of justice, and I hope that MacDonald get a break.

LP: Is Jeffrey MacDonald innocent?

WS: For me to say that he is innocent would require magic. I don’t have that magic. I wasn’t there that night. But there is a reasonable doubt, and because there is a reasonable doubt it is absolutely clear that he should be set free.

Why the MacDonald Case Matters to Everyone

I have read transcripts, articles, books, opinions, blogs and bizarre rantings about psychopaths on Joe McGinniss’ website to help me more clearly see the picture of the MacDonald case. Like Wade Smith, I’ve been struck by how many people speak of absolute certainty about what happened that February night over 40 years ago. As if they had seen it with their own eyes. Such is the power of a good story.

Or maybe there’s something else at work: Picture No. 2 is even more awful to see than Picture No. 1. When a terrible crime is committed, society comes together to find someone to blame and to pay for the collective sense of violation. When you accept Picture No. 1, you’re deciding that Jeffrey MacDonald is the Person Who Must Pay. To dislodge an idea reinforced by a popular book and TV phenomenon would be hard enough, but to add the sickening sense that the wrong man has been paying is nearly unthinkable. It implicates us all.

Harvey Silverglate, a renowned civil liberties advocate, has been an appellate attorney for MacDonald. He is outspoken about MacDonald’s innocence, and when I called him, I could hear the years of outrage in his voice over the way the case has proceeded. Silverglate believes that Jeffrey MacDonald has been railroaded, and that this railroading exposes disturbing trends in our federal criminal justice system. He worries that we are moving into a period in which the finality of verdicts is so zealously protected (a legacy, in part, of 9/11) that new evidence offers little hope of challenging them. MacDonald has had mostly good lawyers, though not always the appropriate ones. But Silverglate points out that those lawyers have been up against an increasingly perverse system in which ancient legal rights like habeas corpus have been tossed aside in the name of preserving convictions at any cost. (See Silverglate's article on the case in Forbes.)

Out of all the evidentiary and procedural twists and turns, I asked Silverglate to name the one that bothered him the most about the MacDonald case.

“The one thing that sticks in my craw above anything else is this: There were lab results. There was a re-examination of the fibers found on the bodies of Collette and the children. These fibers on the bodies didn’t match any fibers found in the MacDonald house. There were fibers from a blonde wig that matched the description of Helena Stoeckley. The FBI lab guy turned over two copies to Brian Murtaugh, the prosecutor. There’s a note attached. This note says: 'Brian, I’m giving you this lab report. I’m giving you an extra copy for Bernie Segal [the defense counsel]. You can give it to him.' Brian Murtaugh says, ‘Sure, I’ll give it to him. I’ll be seeing him.’ Well, Bernie Segal told me that he never saw it.”

In other words, an FBI lab technician trusted exculpatory evidence to a member of the prosecution team. Evidence the defense never saw.

Silverglate predicts that even after examining the new evidence, Judge Fox will not grant Jeffrey MacDonald a new trial. But he is hopeful that the Fourth Court of Appeals, located in Richmond, Va., will take a careful look at the case and as a whole be more favorable to MacDonald. There may be hope that MacDonald will eventually gain his freedom and at least be able to live the last few years of his life outside of a prison cell.

After traveling a months-long journey that has led me from certainty to doubt to horror at a grave injustice, I’m going to turn in this article and then go run some errands and make myself a bite to eat. Mundane things that Jeffrey MacDonald has not been able to do for over 30 years. The simple acts of coming and going as I please and caring for my own basic needs have been denied him. His wife, Colette, and his children have also been forever denied these things -- but not, I have come to believe, by the man who is currently serving three consecutive life sentences.

Tonight when I retire to my bed, I will not feel as safe from unpredictable evils as I did when I was a teenager reading scary stories. Even scarier stories, I’ve found, can be true. Stories about the innocent caught in a machine that perverts every possibility of justice. That kind of story never ends. There is no finality in injustice.

Shares