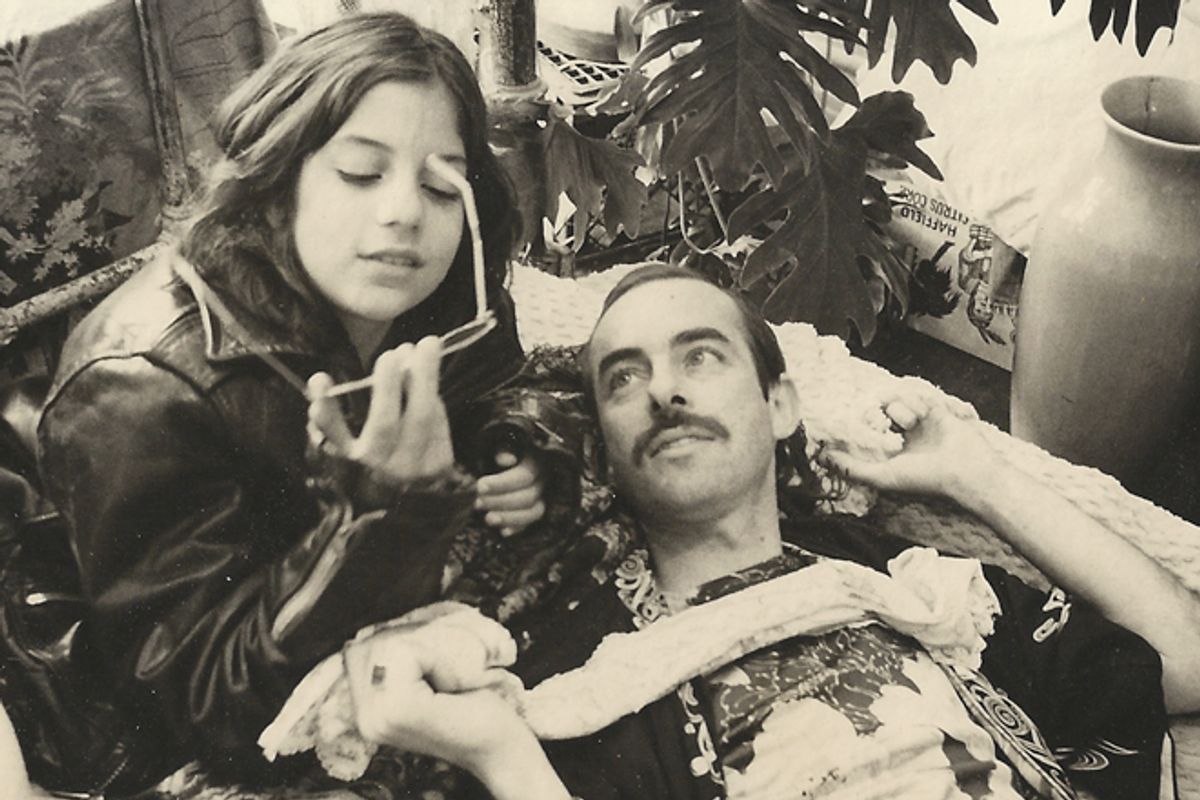

In the spring of 1972, the sexual culture was cracking open. David Bowie released "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust" and Lou Reed released "Transformer." Openly bisexual, the two musicians infused pop culture with a kaleidoscope of strange beauty. Along with Iggy Pop, they were an androgynous space-age force in silver lamé and black nail polish. Listening to "Ziggy Stardust" and later "Transformer" — on which Reed sang, “We’re coming out … out of our closets” — Dad was energized by the possibilities of post-Stonewall homosexuality. He didn’t see his wife and small baby girl as an impediment to sexual liberation. As the student government president at Emory University in Atlanta, he wrote a column for the student paper in which he publicly came out and urged his straight brothers and sisters to join the cause for gay rights as they had joined to fight the war. My mother supported him. Both took lovers on the side. They were living the revolution.

But 10 to 15 years later, that thrilling “golden age” of free sexuality would be equated with death as AIDS started its march across urban centers and then everywhere around America and the world. In those early years of the epidemic, Dad and others were ignorant about the disease — who had it, how to get it — and they were scared. The AIDS test wouldn’t even be publicly available until 1985, at which point half of San Francisco's gay men would already be infected.

In 1986, my dad finally took the test and tested positive for HIV, but I didn’t know it. Reading his private journals, I learned he kept this information from me, then a sophomore in high school, because he didn’t want to burden me with worry. The same year he tested positive, I discovered "Ziggy Stardust." Bowie’s music provided a hip soundtrack to my proto-sexual gropes and my weekends smoking pot with friends. I listened to Dad’s copies of the records, playing them over and over on a cheap turntable in my room. I can still remember the bumpy imprint of his scripted name Abbott, pressed into the cardboard vinyl sleeve in black ballpoint pen.

Six years later, on December 2, 1992, Dad died of AIDS. That year, 1992, was considered one of the high-water marks of the epidemic. Newsweek reported that AIDS was the number-one cause of death for men between ages 18 and 45. Now that I'm finally writing about my father, remembering and researching our time, I re-listened to "Ziggy Stardust"; the strains of the track "Five Years" seem eerily prescient:

“Earth was really dying.”

This discovery inspired me to put together my own mix tape of the AIDS years -- what I call my “Soundtrack to a Plague.” This compilation helped ease my memories and kept me company during the darker days of writing. I offer it, along with highly personalized liner notes, for you.

1. "You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” by Sylvester (From “Step II,” 1978)

In 1973, my mother died in a freak car accident and my father moved us from Atlanta, where we’d been living, to a little railroad apartment off Haight Street in San Francisco. The gay bohemian culture of the neighborhood was then dominated by the Cockettes and their offshoot, the Angels of Light, a gender-fuck theatre troupe versed in glitter and LSD. Sylvester, one of the Cockettes' founding members, would emerge as San Francisco’s first openly queer superstar. He performed at the Gay Pride parades in the Castro and on Dick Clark’s "American Bandstand" and "The Tonight Show." He died of AIDS in 1988.

This song, a titular counterpoint to Aretha Franklin’s "(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman," was one of the biggest hits of the disco era. It’s also a powerful affirmation of how the same-sex love that many still argued was "impossible" could actually make the singer feel “more real.” In his signature falsetto he evokes those heady post-Stonewall years when gays at last were able to experience on a dance floor that feeling of sexual realness taken for granted by others.

2. “Down So Low” by Tracy Nelson with Mother Earth (from “Living With Animals,” 1968)

When I remember the ravages of the AIDS years, it’s not just Dad that comes to mind. We lost neighbors, friends and casual acquaintances. The first friend who got sick was a young writer named Sam D’Allesandro. A poet from Modesto, Calif., he’d changed his name from Sam Anderson to add glamour to his persona and to protect his conservative rancher parents. I was 14 when we met. With his thatch of blond waves, his pillowy lips and his piercing blue eyes, he took my breath away. Sam kindly returned my attention, showing up at my birthday parties, giving me back issues of Interview magazine and introducing me to San Francisco’s New Wave scene. I don’t know when Sam first contracted HIV because when he started to show the symptoms of AIDS, he disappeared from view. Like many young men of the era, he didn’t want to admit that he had “it,” even if having “it” meant increased services and better care. (The stigma of AIDS in this era cannot be overstated.) Sam was 31 when he died.

"Down So Low," by Tracy Nelson was played at Sam’s funeral. A country blues singer influenced by Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, Nelson became a fixture in San Francisco’s Fillmore East scene in the late 1960s. "Down So Low" was covered by Linda Rondstadt, Etta James and an avant-garde singer Diamanda Galas, whose own brother, actor Philip-Dmitri Galas, succumbed to AIDS. But Nelson’s original is still my favorite. Her sustained low moan of longing cuts right to the heart: “When you went away/ I cried so long/ I wanted you to stay.” And that heart, for me, is the knowledge that I never got to say goodbye to Sam. I always thought I’d see him again. Dad and I had meant to visit when we got a call that he’d died.

3. “Heroes” by David Bowie (From “Heroes,” 1977)

Another song from Sam’s funeral. I’ve known this song for years, but I don’t think I really heard it until revisiting this history. A product of Bowie’s fertile “Berlin period,” "Heroes" is ostensibly about love in the Eastern Bloc: “Standing by the wall/ bullets shooting over our heads.” But I can no longer listen to the song without thinking of the gay couples who had to face the AIDS crisis together — couples who had to overcome the obstacle of engaging in a love that was at odds with society and then had to face the greater obstacle of a fatal disease. The line “I, I wish you could swim, like the dolphins, like dolphins could swim” evokes a desire to transcend the limitations of the body, to swim away, to be free — not of Soviet Communism, but of sickness and certain death, which in the '80s and '90s, AIDS surely was.

4. “Freak Scene” by Dinosaur Jr. (From “Bug,” 1988)

I was in my junior year of college and living in France when my father told me he had full-blown AIDS. Against his doctor’s orders, he’d flown from San Francisco to Paris to break the news in person. On that visit, he asked if I could graduate college a semester early and return to our Haight-Ashbury apartment so I could nurse him in his final months. I agreed, seeing no other option, but I when the time came to move home, I resented the responsibility. When I arrived in San Francisco in December 1991, the grunge sound was everywhere, pouring out of cheap café speakers and open apartment windows. This was a sound of nihilism -- and apathy. I wanted to embrace this apathy but couldn’t. The responsibility of nursing my dad required engagement. I sought escape in the arms of a fedora-wearing bass player named Scott who worked at a Haight Street café. He loved Dinosaur Jr., and at his messy Mission apartment we listened to "Bug" all the time. In the back of my mind, I knew I had to return home to Dad. But as I lay on a mattress on the cluttered floor listening to J Mascis’s buzzy guitar, I could feel young again.

It's so fucked I can't believe it

If there's a way I wish we'd see it

5. “What’s Good” by Lou Reed (From “Magic and Loss,” 1991)

In 1989, Lou Reed wrote one of the first songs that dealt directly with the AIDS crisis, “Halloween Parade,” which recounts the effects of AIDS on the annual Greenwich Village tradition. "You'll never see those faces again.” But "What's Good," inspired by Reed's friendship with Doc Pomus, a Brill songwriter who died of cancer, is a more evocative song. Unlike “Halloween Parade,” which lists all of the characters disappeared by disease -- Johnny Rio and Rotten Rita -- “What’s Good” revels in the absurdity of loss itself. The song begins with a powerful guitar riff like a wail of pain before Reed starts in with a litany of pointlessness: “Life's like a mayonnaise soda/ And life's like space without room/ And life's like bacon and ice cream,” before expounding into the idea of life within loss.

Life's like, forever becoming

But life's forever dealing in hurt

Now life's like death without living

That's what life's like without you

6. “Calling All Angels” by Jane Siberry and k.d. lang (From “Music from the Motion Picture Soundtrack 'Until the End of the World',” 1993)

Like “What’s Good,” “Calling All Angels” was featured on the compilation soundtrack to Wim Wenders' film, "Until the End of the World." The whole record is steeped in themes of loss and death, bearing more in common with the climate in which it was released -- the AIDS crisis -- than with the tepidly reviewed Wenders film. Among an already great line-up of songs by Depeche Mode, Nick Cave, Elvis Costello, Neneh Cherry and others, “Calling All Angels” stands out. The song begins in a whisper as Siberry and lang breathlessly call up the saints -- “Santa Maria, Santa Teresa, Santa Anna, Santa Susannah, Santa Cecilia …” -- that are to accompany us. More than any tune on this mix, “Calling All Angels” speaks most directly to the sense of grace that comes out of surrender. The sense that just when you can’t take another day, just when you have nothing left, the world can blow you away with its beauty and light. Siberry evokes this beauty in her fine high-octave reach:

Then it's one foot, then the other, as you step out on the road

Step out on the road, how much weight, how much weight?

Then it's how long, and how far, and how many times

Oh, before it's too late?

Siberry and lang sing: “Don’t leave me alone.” When you listen to this song, you are left not alone.

7. "Sweetness Follows," by R.E.M. ("Automatic for the People," 1992)

My father died four days before I turned 22. I was still living in the Haight-Ashbury apartment where we’d spent most of our life together, a drafty Victorian one bedroom that now seemed impossibly large without him. In those first few weeks after his death, I lit candles every night, studied photographs and listened to the saddest music in my collection — Mozart’s “Requiem,” “Carmina Burana” and “Automatic for the People” by R.E.M. This music especially gave me a way into my grief and helped me absorb what still seemed an impossible truth: that my father was gone and I was alone, orphaned at 21. No song seemed to speak more directly to me than "Sweetness Follows":

Readying to bury your father and your mother …

The deep, sweet cello teased out my sadness but also led me toward a sense of hope, a blueprint of living beyond loss:

It’s these little things that can pull you under.

Live your life full of joy and thunder.

Shares