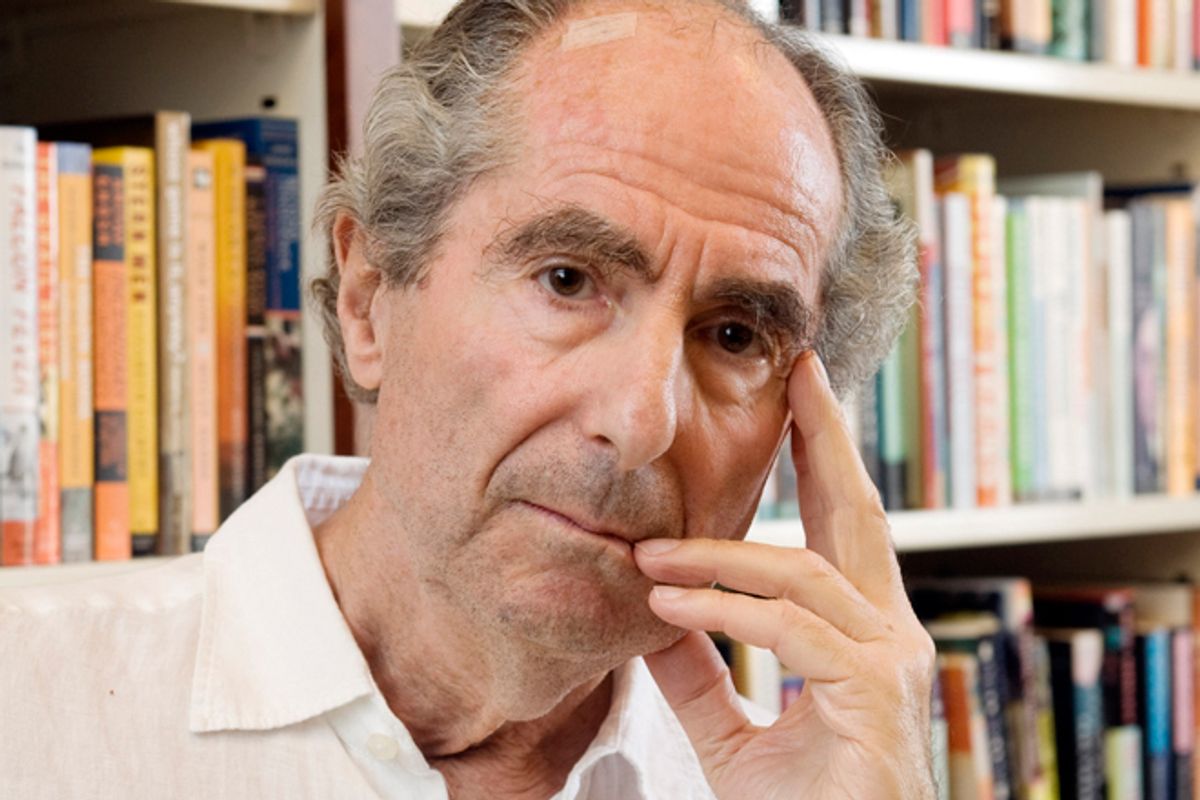

As word came over the transom last week (an actual transom, since I don’t have a working computer) that Philip Roth was retiring, I dismissed it as old, dull news. I’d read the report in the original French, and translated it myself into Turkish and then into Swiss-German just for fun. Then, along with the rest of the literate world, I’d read about it in the Times, which described Roth as a mentally healthy gentleman, happy with his lot.

I knew he was putting on an act, because I’d already heard the opposite from the horse’s mouth. “The Horse” is what I’d called Roth when he and I shared an office space in the late 60s while he was working on Portnoy’s Complaint and I was working on a similar but superior work, Feldman’s Penis. Roth had earned his nickname because he ate a lot of apples and oats, and also because he loved to saddle up with the shiksas. No one knows a writer as well as his contemporaries. Roth and I are as contemporary as they get.

One morning a few months ago, as I sat in my third-floor study in my chateau near the summit of Mount Winchester, my rotary phone rang downstairs. My beleaguered manservant Roger answered it, and came knocking at my door a minute later.

“Mr. Roth would like to invite you to dinner tonight,” he said.

Of course, I accepted the invitation. I don’t go out as much as I used to, because everyone I once knew in publishing is either gone, or, in the case of Joyce Carol Oates, an android. Like John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, Roth and I are the only two of our kind remaining, and by “kind” I mean “men who have written award-winning trilogies about the history of Newark.”

I went to the neighborhood store, stole a bottle of wine, and climbed into the private gondola that the publishing industry installed for me in 1975 as part of a network that allows prominent writers to travel to one another’s homes without having to be bothered by the cares of ordinary people. The gondola system doesn’t have as many stops as it once did in its heyday, but it stays alive, thanks to a MacArthur Foundation grant, in case the Book once again regains cultural dominance over the electronic idiocy that threatens its sacred existence.

An hour later, I was at Roth’s door. He opened it, looking pale and terrible.

“Thank you for coming,” he said.

“It’s always nice to see another working novelist,” I said.

He barely suppressed a sob, and that’s when I knew something was wrong.

We sat by a roaring fire, which I found strange since it was mid-August, and reminisced tenderly about the time we egged Mary McCarthy’s mailbox.

“But she’s dead now, isn’t she?” Roth said.

“Long dead,” I said.

“Mailer. Gore. Updike. Hunter Thompson,” he replied. “All dead.”

“Totally dead,” I said. “Tom Wolfe is still alive, though.”

“Oh, please,” he said.

Everyone had died, Roth said. He’d outlived so many people: George Carlin, Phyllis Diller, Arlen Specter, even, tragically, Junior Seau. They were ash. Still, on he struggled, with the written word.

Philip Roth stared into the fire for a good long while.

“I read your novel ‘Jewball,’” he said.

“Yes?”

“It was unparalleled.”

“Thank you.”

“How can a man your age write with so much energy, vitality, and wisdom?”

“There’s not just one explanation,” I said.

He sighed.

“I read ‘Nemesis,’” I said.

“Yes?” he said.

“It was definitely a book.”

“That it was,” said Philip Roth. “My last book.”

“What?” I said.

“I’m hanging it up,” he said. “I’ve done what I can with the world has given me. And now I just want to spend the rest of my years reading obscure Eastern European poets and watching ‘The X Factor.’”

“But you can’t quit!” I said. “Then I’ll have no competition.”

“You never did have any competition,” Roth said.

“I don’t know about that,” I said. “You came as close as anyone. That book about the masturbating puppeteer was pretty special.”

“Be that as it may,” he said. “I am kaput.”

Dinner was a simple affair, just the two of us, joined by a log wearing a blond wig, googly plastic eyes, and bright red lipstick. Roth kept referring to it as “The Monkey,” and repeatedly asked me, “doesn’t she look pretty today?” to which I replied, “oh, yes, very pretty.” I find that it’s bad form to deny a retired novelist his fleeting pleasures.

We talked for a while of the old days, remembering the times we rolled Truman Capote down a hill and gave William F. Buckley a wedgie in the bathroom at Sardi’s. America had been so trouble-free then, in the 70s. We both wept a little, he over innocence lost, me because he’s always been such a terrible cook.

“Joyce Carol Oates is an android,” he said.

“I know,” I said.

After dinner, we played a little backgammon and had good sport throwing crumpled pages of Updike’s collection of golf essays into the fire. As you age, your tastes refine and you find yourself turning toward the classics, away from trends. Also, sometimes you poop in your pants a little.

Then it was 9 p.m. Roth picked up his log and said, “The Monkey and I are going to turn in. You’re welcome to stay the night.”

“That’s OK,” I said. “I’ll catch the last gondola home. Besides, I’m receiving an important award tomorrow.”

“Of course you are,” he said.

“Don’t worry, Horse,” I said. “That Nobel is still within your reach.”

“Sure it is,” he said, shaking his head sadly. “And so’s the Stanley Cup.”

With that, I left Philip Roth to his retirement. I realized that I’d seen him for possibly the last time, which made me feel a bit wistful, but also happy, because it meant that I’d won at last. The quest for literary dominance is a life-long one, but only the greatest Jews can reach the final round. Philip Roth had come close, but I’d outlasted him.

As I neared the end of my own glorious career, I truly had no complaints.

Shares