So is there really a “war on Christmas” being waged by pinko, lefty, pro-choice, sexually bewildered heathens, as Bill O’Reilly proclaims around this time every year? Well, I don’t know about that, but there’s definitely a war on Christmas movies in that nobody seems capable of making good ones and the list of unwatchably crappy ones grows longer every year. Admittedly, it’s hard for any movie of any kind to be more painful than Tim Allen’s “Santa Clause” series. (There are three of them. Three!) But then, you probably haven’t seen either the 1977 remake of “It’s a Wonderful Life” starring Marlo Thomas or whatever the “Christmas Carol” knockoff from the '90s was called in which Vanessa Williams played Ebony Scrooge.

While the Internet is loaded with lists of supposedly great Christmas-themed movies, almost all of them include the same top few entries: Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life,” of course – mercilessly pilloried by Gary Kamiya in an all-time classic Salon essay – along with “Miracle on 34th Street,” the Bing Crosby “White Christmas” (which isn’t actually good), the 1951 “Scrooge,” “A Charlie Brown Christmas” (which is a TV special, not a movie) and the Rankin-Bass stop-motion “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” (ditto). “Home Alone” and “Elf” are pretty much the only mainstream Christmas flicks made in the past 30 years that anybody wants to watch again, and while the latter is delightful, I find the former almost intolerable (and its Christmas-ness arguably irrelevant).

Sure, some people will stretch the point and stick in any movie that features someone in a Santa suit or a scene with a Christmas tree. All of a sudden “Batman Returns,” “Brazil,” the first two “Die Hard” movies and “Eyes Wide Shut” become Christmas movies, along with lots of other not-so-appropriate-for-the-family fare. Now, some of those, especially the Tim Burton and Stanley Kubrick entries, may belong on a list of films that twist the holiday-movie conventions toward dark purposes, but we aren’t going there today. None of those has exactly the bittersweet mix of sentimentality, sadness and redemption captured in a classic Christmas tale, a combination that seems especially difficult to manage in contemporary cinema, at least without teeth-grinding zaniness, madcap violence or the ickiest forms of emotional terrorism. Maybe O’Reilly has a point!

Here’s the good news about Edward Burns’ new movie “The Fitzgerald Family Christmas,” which goes at this problem head-on: It’s entirely sincere and genuinely not terrible. Burns knows the milieu of his suburbanized New York Irish-American characters at a bone-deep level (enough to induce powerful flashbacks in someone of my background), and the tone of regretful, tragicomic, low-key melodrama he strikes is just right. You may know Burns best from his recurring roles on “Entourage” and “Will & Grace” or his modest parts in Hollywood movies, but he’s been cranking out his own low-budget indies as a writer-director for years without ever quite connecting the way he did with his 1995 debut, “The Brothers McMullen.”

Apparently, it was Tyler Perry who encouraged Burns to get back to his Irish-American, outer-borough roots, which may sound odd at first but makes more and more sense the longer you think about it. (Burns played Perry’s sidekick in this fall’s non-hit “Alex Cross,” which was terrible and which I sort of liked.) So it is that “The Fitzgerald Family Christmas” features two of Burns’ most memorable co-stars from “Brothers McMullen,” Connie Britton and Michael McGlone, and takes place in roughly the same lower-middle-class zones of Long Island, rich with many generations of New York cops and firefighters. (Burns, a native of Woodside, Queens, is a cop’s kid himself.) And so it is, I guess, that it feels pretty much like a Tyler Perry movie for white people, with all the lurching from one subplot to the next, awkward oversharing and emotional directness that implies.

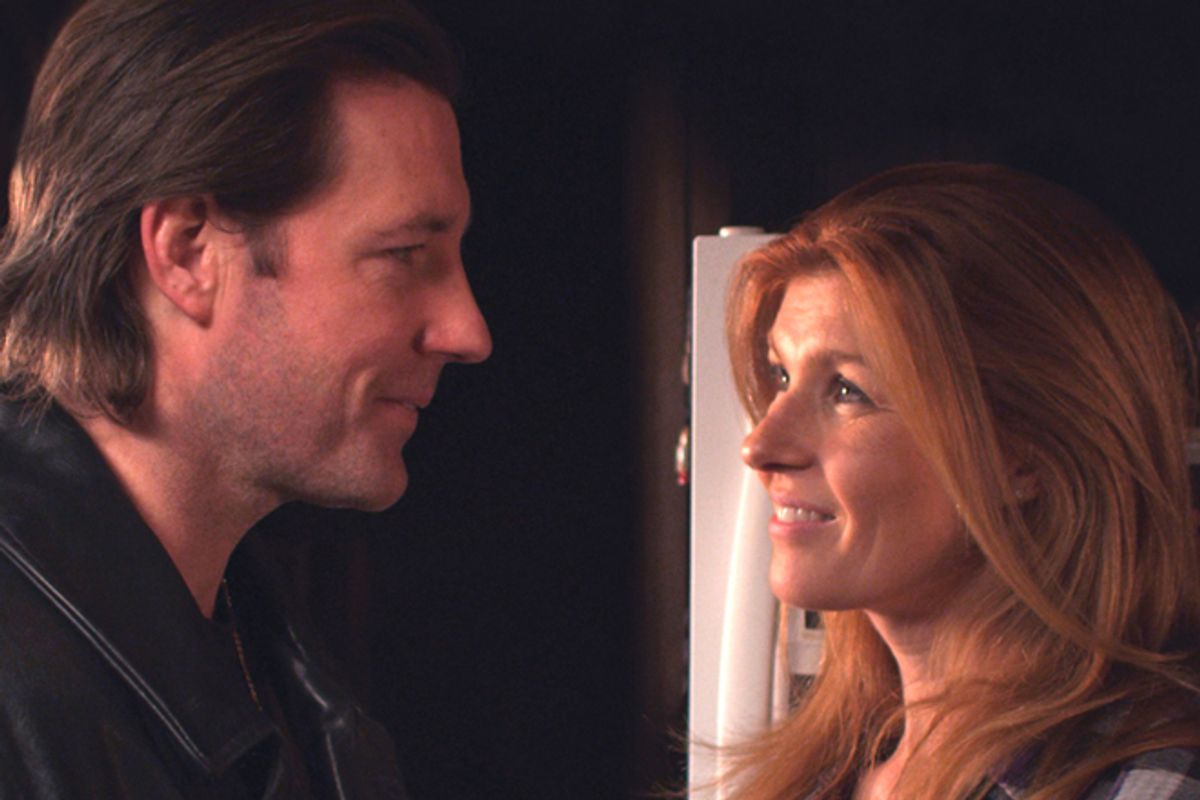

Burns calls on one of the oldest stories in the Christmas playbook: the yarn about a riven family trying to patch itself together for one holiday season. He plays Gerry, the oldest son and chief facilitator of the Fitzgerald household, who tries to wrangle his large tribe of warring adult siblings – there are too damn many sisters; I won’t even try -- and convince his embittered mom (Anita Gillette) to let his exiled but terminally ill father (Ed Lauter) back into the family house for one last Christmas dinner. Those two are terrific and pretty much steal the show, but Burns remains an agreeable presence throughout, and the emotions mostly ring true, even if the comic elements feel overly broad and individual episodes are hit-and-miss. Britton -- who’s, of course, far more famous than she was in 1995 (and more so than anyone else in the cast) -- gets what amounts to an extended cameo as the nurse who breaks through Gerry’s wall of manly loneliness. Her character turns out to be a Bostonian and a Red Sox fan, and even that won’t scare Gerry away.

If “The Fitzgerald Family Christmas” might be the one movie of 2012 that Bill O’Reilly and I both like, he might not appreciate me saying that it feels like a stripped-down American remake of French director Arnaud Desplechin’s marvelous ensemble drama from 2008, “A Christmas Tale,” with Catherine Deneuve as the cancer-stricken matriarch of a feuding clan. (Nor is that the only recent art-house treatment of Christmas themes. Martin McDonagh's "In Bruges" might be the most overtly Christian Christmas movie in years, but not in a way Bill O'Reilly would recognize or approve of.) But one fair-to-middling Christmas movie that does not involve dynamiting the neighbors’ lawn or Eddie Murphy dressing as a 300-pound woman does not solve the Yuletide cinema problem, which I think is real.

I hesitate to build an argument around some sentiment like “Christmas used to be more innocent,” because that’s an inherently stupid thing to say. There’s a germ of truth to that, though: As the holiday season has swollen in size, both in kitschy symbolism and in economic importance -- an element satirized more than 60 years ago in “Miracle on 34th Street” -- it makes those of us old enough to know the dark truth about St. Nicholas increasingly anxious and cynical about the whole business. Holiday entertainments are supposed to embody homilies about the “real meaning” of Christmas, but those of us out here in Consumerland have good reason to roll our eyes at that one. If Christmas, in the American meaning of the holiday, has long been an ideological construct used to paper over economic necessity, the paper has worn pretty thin.

Is there a war on Christmas that makes the holiday seem increasingly hollow and the movies that claim to celebrate it seem tawdry and desperate? Sure there is, Bill, but it’s not being waged by lesbians and atheists. It’s being waged by an economy that has driven the real incomes of ordinary Americans downward year after year for four decades while demanding ever more exorbitant displays of holiday largess. We work harder for less money and are expected to spend more and more on electronic gizmos that fill up our diminishing leisure hours. It’s pretty tough to sit by the fire in a cardigan thinking about the spiritual meaning of Christmas amid all that, and the problem with watching “It’s a Wonderful Life” one more time – in all its naked, painful American religiosity -- is that it reminds us that, in theory, it doesn’t have to be this way.

"The Fitzgerald Family Christmas" is now playing throughout the New York metropolitan area. It opens Dec. 14 in Coral Gables, Fla., Fort Lauderdale, Fla., Gloucester, Mass., Key West, Fla., Otsego, Mich., Pittsfield, Mass., Wilmington, Del., Boise, Idaho, Ogden, Utah, and Columbus, Ohio, with other cities to follow. It's also available on-demand from cable, satellite and online providers.

Shares