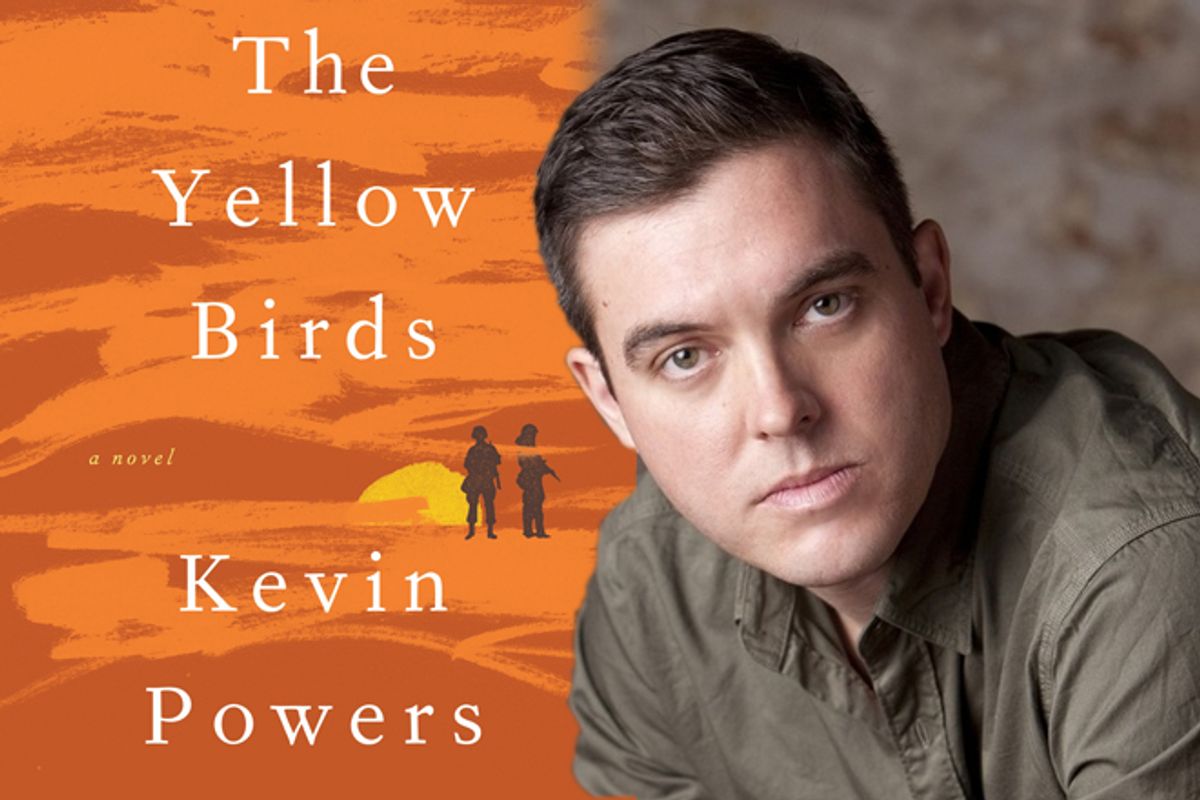

One of the most feted books of the season is a debut novel about the Iraq war, Kevin Powers' “The Yellow Birds.” It has garnered gushing blurbs from famous authors, the cover of the New York Times Book Review, a National Book Award nomination, TV appearances, the Guardian First Book Award, and laudatory reviews from nearly every corner of the literary establishment. And this past weekend it added a New York Times Best Book of 2012 to the list. By general consensus, “The Yellow Birds” is a classic of war literature.

There’s just one little problem: The novel doesn’t measure up to the praise.

Indeed, the book is beset by so many deficiencies you’re tempted to wonder what the critics have been smoking. The answer, in the words of one veteran friend, is Martialuana. Let me define the term I've coined: It's a stimulant, known to effect in its user a long-lasting, sometimes undeserved, high about American armed service members and veterans. Prevalent in establishment circles. Often used to assuage guilt for the burden veterans have borne over the last decade.

Veterans have benefited greatly over the last decade from the widespread use of this very legal drug. No government institution is more respected than the armed services, according to Gallup, and veterans as a constituency have become virtually untouchable. In corporate marketing parlance, “Hero” has become the stock term for anything that has to do with veterans. It’s hard to go a week without stumbling across the latest “Hero Summit”’ or “Hero Pass” or “[Insert Big Corporate Name] Salutes Our Heroes.” For those of us who have worn the uniform — I served as an officer in the U.S. Navy — the ubiquity of the label is laughable. Audie Murphy is a hero; Joe Soldier only one in his mind.

This esteem has been, by and large, a good thing for veterans, earning them the new GI Bill, hiring preference and free admission at Sea World, among other things. Considering their sacrifice, few would claim it unearned. But this attitude has also started crossing over into the realm of art, and here the effect is pernicious.

Kevin Powers, an Iraq war veteran and an MFA poet, is just the latest and most prominent example. The Washington Post’s Ron Charles, one of the few critics willing to remark on the phenomenon, summed it up well in his mixed review of “The Yellow Birds”: “Tempering one’s enthusiasm for a vet’s war novel seems, if not unpatriotic, then at least peevish and small-minded. Surely, anyone who has survived battle and lived to write about it this well deserves to ride through the bookstore under a flurry of confetti made from congratulatory blurbs.” And that is precisely what the critics and the literary establishment have done.

What those penning the encomiums don’t seem to understand is that by praising Powers’ underwhelming novel, they undercut the very veterans they are trying to champion. Rather than being judged on the same narrative and aesthetic scale as their non-veteran peers, veterans find themselves being graded on a curve – the old A for effort (though a gold star might be more fitting). After all, Powers survived a war and wrote about it while all those soft MFAs continue writing soft tales about soft lives. No matter that “The Yellow Birds,” far more than most MFA novels, is an exemplar of writing workshop indulgence.

Even the term "novel" is a bit of a misnomer when applied to “The Yellow Birds,” since the story of Pvt. John Bartle’s tour in Iraq and his subsequent travails in the States lacks the narrative drive and coherence that a novel traditionally provides. It reads instead as a collection of linked stories, with all the forward momentum of a slug in molasses. And the few times the narrative actually does gather some momentum, Powers does his best to undermine it with seemingly endless landscape descriptions. There’s never a sky not worthy of a few adjectives (“vast and catacombed” or “ruddy mackerel” or “brittle charcoal”) or a tree or flower left unidentified. This is certainly a poet’s novel, in every bad sense of the word.

But a boggy lyricism is the least of the novel’s problems. Characters and plot devices seem to come straight from the Great Big Book of War Clichés: the tough sergeant; the blustering high-ranking officer; the journalist who asks about “the rush” of war; “Murph"; and the soldier who promises mom to bring her son home (shocker: He dies!). Powers constantly reaches for a grandiloquence that his material and, more important, his voice simply cannot sustain. He veers wildly from a Hemingwayesque brevity to a tortuous maximalism, each paragraph clotted with clauses and metaphors, straining like oxen yoked to a boulder for some universal truth that isn’t coming.

My biggest issue with the novel: Powers does a poor job of portraying the war in which it is set. As one veteran put it to me, “The Yellow Birds” is a Vietnam novel that happens to take place in Iraq. It is the novel’s duty to illuminate truth via language and character, narrative and artifice. And “The Yellow Birds” ultimately comes up short in both truth and aesthetics. Powers may have the facts nailed, but the overwrought tone and atmosphere are completely counter to the chaotic, postmodern, mundane and terrifying place Iraq actually was. There is nothing here that has not been done better in the war memoirs of Nathaniel Fick, Matt Gallagher, Brian Castner and others, or even in David Abrams' flawed but fun Iraq novel “Fobbit.”

Now I do need to clarify something: “The Yellow Birds” is not a bad novel. Rather, it is a mediocre novel written by a young writer with a lot of talent. Powers has an ear for language that a thousand would-be novelists would give their left arm for. But talent, unformed, does not a great novel make. And hyping a novel of modest ambition as a classic of war literature does its author no favors – because in the end it’s readers who pay the price. Expecting a classic, many readers will come away disappointed, and that much less likely to give a true classic novel about the war(s) a chance.

It may seem overly harsh to judge critically the heartfelt effort of someone who has borne the price of this country’s wars. And some may argue there is nothing wrong in giving the guy a handicap when it comes to the scoring. But it is a critic’s duty to not take such things into account. And with “The Yellow Birds” it is all too obvious that who the writer was mattered as much as what he wrote.

Unfortunately, Martialuana doesn’t only affect the critics; the secondhand smoke has started to warp the minds of the veteran writers themselves. As any high school student applying to college knows, it never hurts to check the minority box on the admissions application. And veteran writers know the easiest path to print is to write on war, veterans’ issues and the military. If he (or she) doesn’t, he is in for a far harder road. I can attest, since I’ve tried both routes.

The result is the “Veteran Writer,” his authority derived from what he was, rather than how he writes. He is a veteran first, a writer second. He has been branded with the golden V, and to the outside world it is this identity that subsumes all others. No one thinks of Philip Roth, Thomas Pynchon, Norman Mailer, Tobias Wolff, John Dos Passos and Cormac McCarthy as Veteran Writers, but every one of them wore the country’s uniform. Yet the likes of Phil Klay, Roy Scranton, Matt Gallagher and others are known as much, if not more, for being Veteran Writers than for simply being writers.

It does not take a veteran to write about war and the military. Ben Fountain’s “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk,” the best novel yet about America’s war experience, makes this clear. Yet every time a novel, memoir or piece of journalism written by a veteran is judged by a different standard, the Veteran Writer trope is reinforced. Veterans trying to make their mark on literature already find themselves confronted with a gap that separates them and their writer peers, mirroring the gap that already exists in the society at large. If critics don’t do their job, this gap will only widen.

“The Yellow Birds” is a noble effort by a gifted writer, but the classic novel about the last decade of war and terrorism has yet to be written. And when – if – it appears, whether the author is a veteran or not won’t have a thing to do with it.

Shares