By the time he was two-and-a-half years old, my son was obsessed with Michael Jackson -- belting out garbled lyrics to "Billie Jean," dancing along to "Smooth Criminal" and "Bad," warning us about how scary "Thriller" was. His obsession made sense to me because Michael Jackson made sense. I had been a child of the late 1960s and '70s, growing up in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn (the old Bushwick, not the one where white people now live). I grew up on the end of White Flight (the last white family left our block in 1971) in the land of the splendidly rounded afro, where the chants of the Black Panthers and the Young Lords flowed from our tongues not because we understood their enormity, but because they rhymed and felt powerful. We saw ourselves reflected back in the works of Nikki Giovanni and Pedro Pietri. We could be the next Shirley Chisholm or Hermon Badillo. "Say it loud," James Brown screamed out to us. "I’m black and I’m proud." Nina Simone told us we were young, gifted and black. Jesse Jackson commanded us to say "I AM Somebody!" And we were. And Michael Jackson represented all our fabulosity wrapped up in one small boy and his brothers.

My mother migrated from South Carolina in 1968 and found a freedom in New York she could never feel back home. But the South stayed with her – in the salted peanuts and pound cakes relatives sent, in the slow Southern lilt of her words and whenever the issue of race got talked about. Which was often. On weekends, she picked out her afro wig, sprayed it with Afro Sheen Holding Hair Spray and sat it on its Styrofoam holder, her own short, natural hair now free for 48 hours.

When Michael Jackson and his brothers showed up on the television screen, my sister and I kissed the glass while my brothers practiced the group’s smooth moves behind us and my mother looked on in proud, quiet adoration. On the rare occasions our mother let us watch an Elvis Presley movie, we knew better than to go near the screen. It was simply by the grace of having a television with only six working channels and a rainy weekend day that he was even allowed inside our house. Over and over again, we heard how Elvis had been quoted as saying the only thing a black person could do for him was shine his shoes. We had been lectured ad nauseam about how he’d stolen our moves, our style of singing, even a song or two or three. He was deeply unloved in our house and in many houses in our predominantly black and Latino community. But my sister and I secretly loved him. The difference was, we loved Elvis from a distance. We knew we’d never meet him, knew he’d never look us in the eye and truly see us. We knew the girls he loved on and off screen were not Black and Beautiful – as we were being taught we were. We knew Elvis would not understand our amazingness. We knew he was different. But it didn’t matter. We had Michael. Michael Jackson and his brothers looked into that camera and saw us. His skin was brown like ours. His hair was thick and natural the way ours was. His clothes were, if we could have afforded them, clothes we would have worn. And in our small place in the universe, our family had an even deeper connection. The Jackson Five, it was rumored, like us, were Jehovah’s Witnesses. At a time when our conservative, misunderstood (even by us) religion was something that set my sister and brothers and I far apart from even our closest friends, here we were watching a superstar who believed in Armageddon, the resurrection, the New World, Jehovah. Here was an idol who was not allowed to celebrate birthdays or holidays, who, when he was not on the road, probably had to sit through the same Monday evening bible studies, Sunday morning Watchtower studies, Thursday night Ministry School and the short prayer "Thank you, Jehovah, for this food and all other blessings, through your son, Christ Jesus. Amen” before every meal. The possibility of one day being in the same place with Michael Jackson, either in this world or the next one, made amazing sense to us. After all, it was a part of God’s plan. Or so we thought.

But the years passed.

We grew up and away from the religion. We came out or stayed closeted, went on to college or got jobs out of high school. As we took steps out into the world, we had "Black Is Beautiful" and "Boriqua Forever" deeply ingrained in our blood, and our sense of who we could be and were becoming made us bold and moved us forward. As Michael Jackson changed physically, so did we. We gained weight or didn’t, grew breasts, straightened our hair, tweezed our eyebrows. And even though we had been taught that "Black Don’t Crack" -- that the melanin in our skin kept the wrinkles away and that only white people did crazy things like plastic surgery -- some of us had a little work done around the eyes, permanently straightened our hair, took a little fat off the hips and stomachs, narrowed our noses just a touch. We did not want to be white or even "less black." We wanted to be a little bit different.

As young adults, we did not know the deep history of Michael’s physical abuse and did not understand the trauma of his childhood. While we looked into the mirrors of our future selves through the people who had come before us, Michael looked at us. And to him, millions of people screaming must have reflected nothing more to him than a future only slightly dimmer than his past. As a child growing up with the abusive Joe Jackson as a father, who was the parent imprinting the depth of his beauty? Who was his crew of friends telling him how amazing he was, deeply knowing him and meaning it?

As a community of color, we saw the tragic impact of the world through Michael’s ever-changing face and eyes. He had seemed so lucky as a little boy on that black-and-white television screen of our childhoods. Now, we were realizing, we were the lucky ones. That while those in the world who could never truly know us labeled our community ghetto and called us underprivileged (later to be replaced with "underserved" and finally, just plain "urban"), we were being shielded and coddled by parents who were going to make sure our sense of beauty and worth would be felt all the way to our marrow.

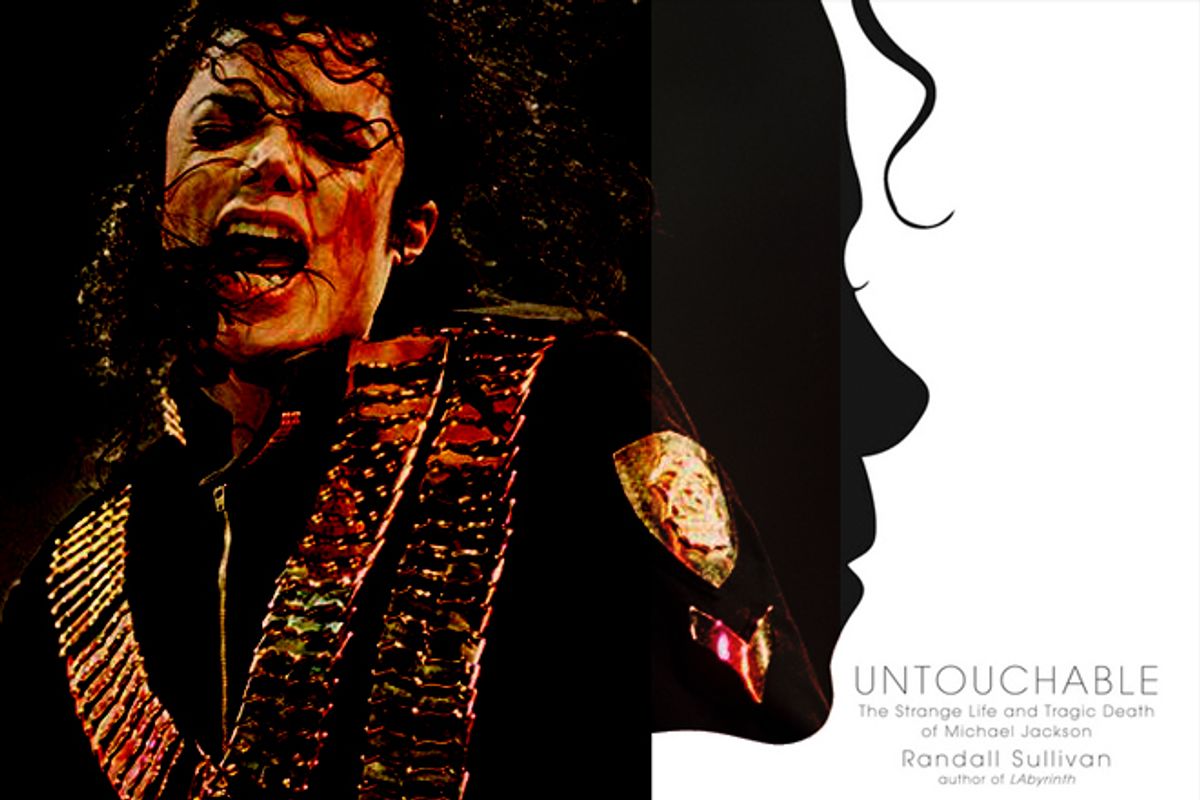

This is why when I read the title of Randy Sullivan’s exhaustive and exhausting biography, "Untouchable: The Strange Life and Tragic Death of Michael Jackson," I was already put off. Whose life isn’t strange? Whose death isn’t tragic? What kind of outside gaze could come up with such unsympathetic title? How could Randy know anything if he didn’t sit, as we did, in front of that TV screen as the world of Black and White and what it meant to be a child of color inside that world settled over us. And years later, when white people asked me how do I explain “white” Michael Jackson to my children, I answered “What’s there to explain?” Because anyone who has spent a minute in this country knows one can’t "become white." Michael Jackson was an amazing performer with a devastating past who had no mirrors with which to see his beautiful self and thus wanted to change the face I loved as a child. He was no less black. No less Michael. At least, not to the people who really saw him.

Sullivan brings an amazing amount of detail to the biography. Ask me about Michael’s childhood bedroom. I can tell you now. Ask me about Jackson’s lawyers, lawsuits, hangers-on and addictions to benzos. I know it. Ask me about his spending habits, and allies, and enemies, and allies-turned-enemies. Ask me about Michael and his kids going to Las Vegas and leaving Las Vegas and how they traveled and the size of their hotel rooms. Yet I found myself disengaged and downright bored by the minutiae. It felt as if Sullivan realized very early on that he had no clue about who Jackson really was, and rather than figure this out (and maybe even talk a little bit about what it means to be a white man writing about a black man), he attempted to fill the holes in with tiny, unnecessary details. Page after page after page of them.

And because every detail is meticulously penned and reported with such an unexamined lack of empathy or self-reflection, by the time I got to the middle of the book, I no longer wanted it in my house. It did not deepen or lessen my feelings for or understanding of Michael Jackson. Yes, there are 601 pages in this book, followed by another 175 pages of notes and acknowledgements. To some, this might seem important – that someone would want to spend this much time and paper investigating a life. What saddens me is that Sullivan seems to have missed the most important part of that life – that it changed and continues to change the lives of people of color around the world.

My son is nearly five now, and although he has outgrown his Michael Jackson obsession, whenever one of Jackson’s songs come on, he stops whatever he’s doing and looks off as he listens to the words. When ask him if he’s going to sing along, he sometimes does; other times, he says, "I’m just listening." Maybe he already knows what Sullivan never learned – that Michael Jackson’s story, like his music, is inherently understood by those who truly listen. And for those who do, no other explanation is needed.

Shares