Compared to British fantasists, American writers have often felt the lack of a deeply rooted national mythos. In place of ancient folklore handed down from generation to generation, we have a shallow, polyglot history imposed over a native culture that was demonized and in many cases eradicated by European settlers. American writers ranging from Stephen King to Michael Chabon have tried to fill this archetype gap, but it isn’t always easy to create imagery and ideas that resonate, which is one reason why so much fantasy falls back on Anglo-Saxon and Celtic motifs.

Felix Gilman’s two vaguely steampunkish novels, “The Half-Made World” and the just-published “The Rise of Ransom City,” come closer than many previous efforts to nailing America’s conflicted collective unconscious. The setting is not, of course, called America (any more than Middle-earth is called England). Nevertheless, it’s instantly recognizable as a version of the Wild West, a frontier land with towns named Clementine, Gibson or Jasper City, sandwiched between the distant, civilized East and, to the West, a region known only as the Rim. Way out West, as Harry Ransom, the narrator of “The Rise of Ransom City,” explains it, are “territories where the future was still open, where laws were still unsettled — I mean not least what they call the laws of nature, which as everyone knows are different on the Rim.”

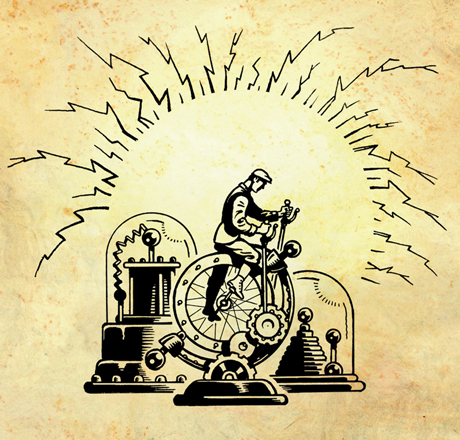

Harry, an ambitious and idealistic inventor with a slick line of patter always ready to hand, roams this in-between terrain, peddling assorted inventions. One is the Ransom System of exercises, always a good bet in a land of perpetual self-improvement, but his true claim to potential fame is something called the Ransom Process (or “the Ransom Infinite-Escalation or the Ransom Unmoved-Mover Process, or the Ransom Free-Energy Process, or the Ransom Light-Bringing Engine”), a means of generating light wirelessly and without need of fuel. Harry achieves this miracle via a contraption he calls the Apparatus, and as he travels from town to town exhibiting the device, he tries to sell the locals on setting up a public lighting system that will illuminate streets and houses, gratis. As attractive as this proposition may seem, the Process has a tendency to “run wild” and cause explosions, so most of his demonstrations end in screaming and pandemonium.

First introduced in “The Half-Made World,” Gilman’s version of the Old West is plagued by a long-running conflict called the Great War. There are two sides: the Line, a regimented, totalitarian industrial regime, and the Gun, whose vainglorious outlaw agents sow chaos and perpetrate gleeful violence wherever they go. Each side is ruled by mysterious entities whose origins are the subject of much debate. Commanding the Line are the Engines, embodied in battleship-sized locomotive trains. The agents of the Gun, once ordinary men and women, have sworn to serve the demonic beings that reside in their elegant and deadly weapons. If the vehicle — gun or engine — they inhabit is destroyed, these demigod-like entities simple move into a new one.

Harry’s activities annoy the Line, which has forcefully bestowed exploitatively-priced electric power on a few Western towns and doesn’t appreciate the competition. He’s pretty small potatoes, however, until he hooks up with two fugitives, characters from “The Half-Made World,” in search of a fabled weapon said to be capable of conclusively killing both Engines and Guns. A particularly spectacular malfunction of the Apparatus leads both sides to assume that Harry himself is in possession of the weapon, and the young inventor is forced into hiding.

As with most of the best fantasy, there’s hardly any magic in “The Rise of Ransom City.” Harry rarely encounters either Gun or Engine, and while the action does culminate in a battle, he largely observes from the sidelines. The novel’s milieu is a piquant, Twainian mix of itinerant entertainers, down-at-heel dreamers, townsfolk, newspaper reporters, snake-oil salesmen and would-be entrepreneurs. Harry spends time working on a steamboat and building equipment for a stage magician. Like regular people everywhere, the primary characters in this novel become the collateral victims of larger forces that battle for causes they don’t understand. “In my view,” Harry writes (the novel purports to be his autobiography), “the armies were there for no particular reason at all. The fighting was a purpose in itself.”

Harry himself takes as his role model one Alfred Baxter, a “business magnate” whose bootstrapper autobiography Harry regards as his bible. (He spends a lot of the novel trying to get a meeting with Baxter, so he can tell him all about the Ransom Process.) To Harry’s mind, Baxter has defied both Line and Gun to become “the richest and grandest and free-est” man in the world,” a judgment the reader will come to doubt even before Harry learns otherwise. It’s possible to see “The Rise of Ransom City” as a rumination on the hubris of the American Dream, if by “dream” you mean a form of individualism that holds it possible for a man to be all three things — rich, grand and free — at the same time. (Not to mention a rejoinder to the pop-culture fantasy that cathartic violence can set everything to right.)

These are big ideas, a diagnosis of the American character as alternately possessed by ruthless utilitarianism and nihilistic self-aggrandizement, but they simmer below the surface of “The Rise of Ransom City” rather than running the show. The novel is also a sepia-toned panorama of eccentric and moving Western characters, and it has the lovely, unvarnished texture of Harry’s voice, eloquence in the guise of plain speaking. (“I was always a good talker,” he admits.) This is all the more surprising when you consider that Gilman, his creator, is British. But sometimes it’s the outsiders who see us most clearly.