Of all the bands that seemed ripe for reunion, Nirvana had to be near the bottom of the list: The death of Kurt Cobain in 1994 left the trio without a singer, songwriter or guitarist, and replacing him, really, was unimaginable.

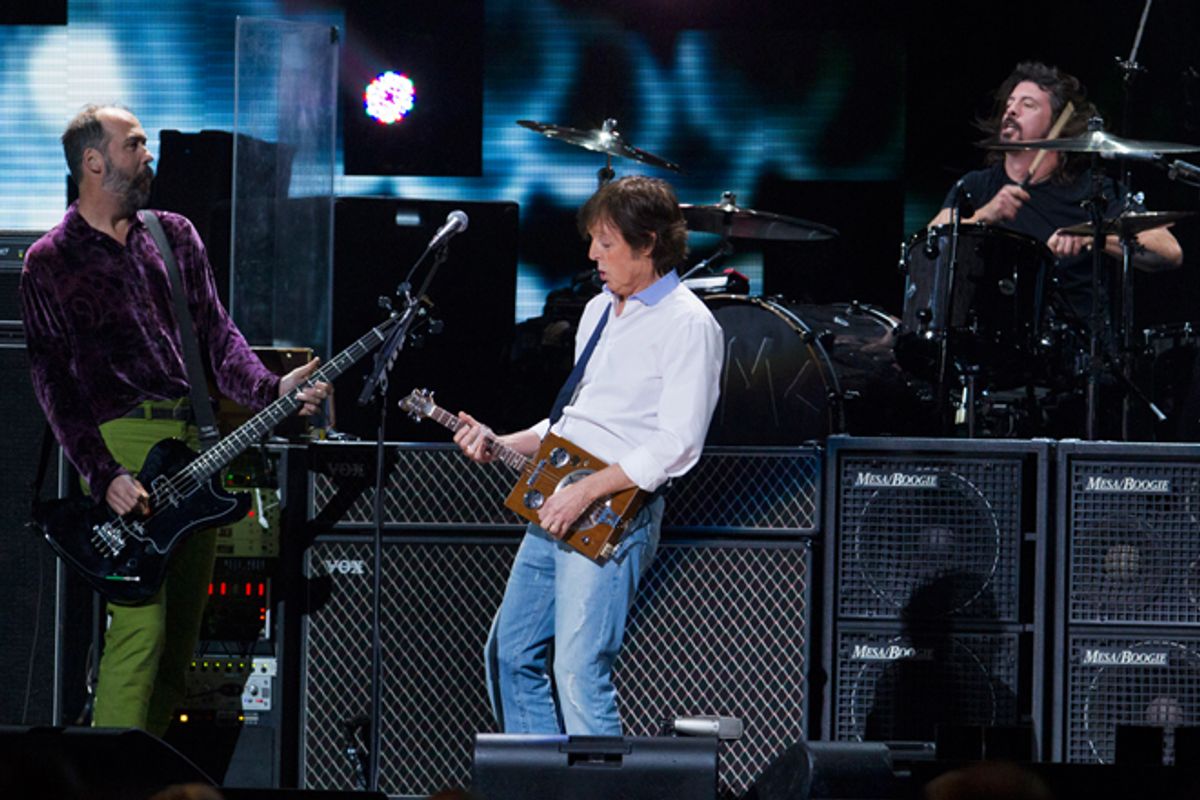

And yet there were Dave Grohl, Krist Novoselic and touring guitarist Pat Smear, onstage at Madison Square Garden last week with substitute frontman Paul McCartney, storming through a new song called “Cut Me Some Slack” — the first time the surviving members of Nirvana had performed together in public since Cobain’s suicide. And there they were again, on “Saturday Night Live,” in what seemed more like a plug for Grohl’s upcoming documentary “Sound City,” about the beloved (defunct) Los Angeles recording studio of the same name. (“Cut Me Some Slack” is on the soundtrack, don’t you know, and — what a coincidence! — available for purchase right now.)

They do get cut some slack for the first one, because their performance came as part of the “12-12-12” concert to help raise money for victims of Hurricane Sandy. The promise of a Nirvana reunion certainly juiced interest in the benefit when word leaked out before the show, and hopefully the buzz translated into the donations.

But it should have been a one-off gig, like Pink Floyd at Live 8 or Led Zeppelin’s 2007 concert in London. Not because this version of Nirvana didn’t sound good (they did) but because they have nothing to gain from any more permanent reunion. No group of their stature does. The band was stormy, imperfect and achingly incomplete — all of which are key underpinnings of Nirvana’s legacy.

Legacies are a tricky concept. Rock ’n’ roll shouldn’t be a museum piece, preserved behind glass, but bands are products of their times. Some acts have shown an ability to evolve beyond their original contexts, but most don’t — and not for lack of trying. Nirvana never got the chance, which roots them firmly at the forefront of the alt-rock explosion in the early ’90s, when the trio released a handful of singles and albums before Cobain’s death ended the band. And that was that. Apart from various reissues, compilations and public name-calling by Cobain’s widow, Courtney Love, Nirvana was essentially a thing of the past.

For a lot of bands, though, that isn’t that at all. Almost nobody stays broken up anymore. It’s become a rock ’n’ roll rite of passage for bands to split, reunite after a few years and cash in. Phish did it, along with No Doubt, Bush, Blink-182, the Spice Girls, Pavement and plenty of others, including the horrifying merger of the Backstreet Boys and New Kids on the Block into one mega-boy band. Even the death of a singer isn’t a barrier anymore: A version of Queen toured with Paul Rodgers on the mike, and INXS trolled reality TV for a vocalist to replace Michael Hutchence before calling it quits again this fall.

Getting the band back together is a savvy business decision, given the financial rewards involved, but it’s usually a questionable creative move. In fact, creativity often seems to be a secondary consideration, if it’s even a consideration at all: Plenty of reunited bands simply flog the old songs on the road for a while, which is exactly the sort of nostalgia trip the fans usually want.

Bands that do opt to write new material face a different challenge: namely, one of living up to the songs that made a reunion feasible in the first place. It’s standard writ that old bands playing new songs in concert is essentially inviting the audience to hit the bathroom or the snack bar, and for every group like Mission of Burma that comes roaring back after a 20-year break with albums as strong as the ones they made the first time around, there are many more acts that shouldn’t have bothered (remnants of Lynyrd Skynyrd: Please stop). That’s not as big a knock as it sounds: It’s astoundingly difficult to reignite the spark that led to those old songs. Times and life circumstances change, and the passion, hunger and determination of youth often fade into self-consciousness and a tendency to overthink, which translates to music that sounds forced — an effect that’s amplified when it’s clear the musicians are only still willing to tolerate each other for the money.

Which brings us back to legacies. Our culture prizes endurance as a sign of strength, and while that’s true for distance runners and starting pitchers, “long-lasting” in music is not necessarily a synonym for “awesome,” Bruce Springsteen and Neil Young aside. Even they have released crummy albums — they’re just overshadowed by all the good ones. But what chance does Nirvana without Cobain have? Sure, it would have been interesting to see what they would have done, but there’s no guarantee that Nirvana with Cobain could have maintained quality control over the long term.

The truth is, not everything has to last forever, nor should it. It’s inevitable that bands break up, and there’s a kind of integrity to letting things lie, to letting the music exist as a marker of the time and place it was created. Influential acts like the Smiths and Uncle Tupelo each disintegrated after four albums, and former members of both groups are adamant that they will never reunite. Good: They’re honoring the music they made by leaving well enough alone.

Grohl and Novoselic should do the same for Nirvana.

Shares