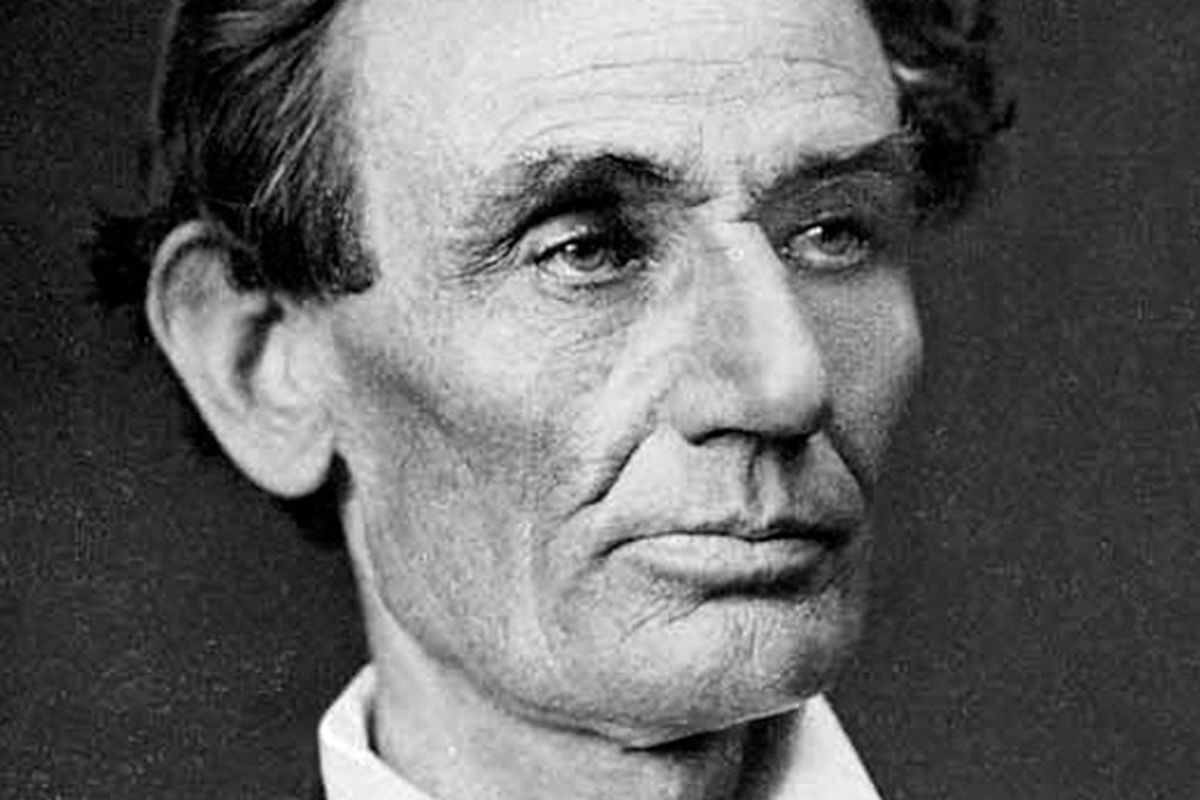

ONE OF THE MOST gratifying aspects of Steven Spielberg’s movie Lincoln has been the debate that its release has generated among historians and journalists, a debate more important than the movie itself. What were the complex dilemmas that Lincoln faced as President? What were the political realities and conduct of the time? How should we interpret the decisions that Lincoln and others made? What role did slaves and free blacks play in their own liberation?

Despite the fact that the film focuses on a short period of time in Lincoln’s presidency and deals primarily with the political cut and thrust associated with the passage of the 13th Amendment, there is a real sense in which the film can be described as deeply philosophical. Lincoln is portrayed as a man of discipline, concentration, and energy, all characteristics that sociologist Max Weber defined as part of the serious politician’s vocation. By forging an effective and realized political character — one aspect of Weber’s definition of charismatic authority — an astute politician can change the nature of power in society. By controlling his all-too-human vanity, he can avoid the two deadly political sins of lack of objectivity and irresponsibility. For Weber, a certain “distance to things and men” was required to abide by an “ethic of responsibility” for the weighty decisions that leaders are often required to make.

Lincoln has always been a man for all political seasons. There is Lincoln the principled politician, who believed that war was a necessary and legitimate means to sustain the Union; Lincoln the timid compromiser, who as late as 16 months into the war declared that if he “could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it”; and Lincoln the reconciling healer of “With malice toward none, with charity for all,” of the Second Inaugural.

Conservative New York Times writer David Brooks argued in a November 22 column that it was Lincoln’s internal strength and ability to compromise that allowed for the possibility of public good. For Brooks, the temptations of fame and ideological rigidity are what undermine the average politician’s ability to compromise. Weber called the losers in that wrestling match with fame, political “windbags.”

But for liberal Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne, it was Lincoln’s principled stand on the 13th Amendment and the need to ban slavery that accounts for his iconic status as one of our greatest Presidents. In an October 19 piece, Dionne encouraged Obama to “follow Lincoln’s example” by refusing to compromise with current economic and financial injustice.

While most political journalists have viewed the film with an eye on the current political stalemate, our most prominent historians have looked for accuracy and context.

Columbia University Professor Eric Foner, one of the most eminent historians of the Civil War and Reconstruction, sees the film as an “inside the beltway” rendition of the period. In a recent interview on Jon Wiener’s KPFK radio show, Foner points out that during the period that the movie covers, General William Tecumseh Sherman’s Union Army was marching through South Carolina. Slaves, in full-scale rebellion, were seizing plantations and “occupying” the land that they had worked. Slavery was “dying on the ground,” Foner insisted, not just in the House of Representatives. In Lincoln, “We are back to the old idea of Lincoln freeing the slaves by himself,” Foner says, reinforcing a one-dimensional view of a complicated historical process. The problem is not what the movie shows but what it doesn’t show.

Additionally, as Foner points out in his Pulitzer Prize wining book, The Fiery Trial, Lincoln was “non-committal” during the failed 1864 attempt by Congress to pass the 13th Amendment. This was at a time when abolitionists, including the Women’s National Loyal League headed by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, were delivering “monster” petitions to congress urging them to pass the amendment. They had gathered 400,000 signatures by mid 1864, but Lincoln was pushing for state-enacted emancipation in the border-states and occupied south.

Lincoln was also a “passive observer” of Senator Charles Sumner’s “crusade” to pass legislation that would allow blacks to carry mail, ride on streetcars, and testify in Federal courts in the District of Columbia, although he signed the bills that managed to pass in Congress. It was not until John C. Fremont was nominated for President in May 1864 — as a challenge to Lincoln — that Lincoln encouraged his party to embrace a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery.

Foner also challenges the “race against time” plot of the movie, whereby recalcitrant Republicans and pro-slavery Democrats stall the work of Congress while a Confederate peace initiative threatens to undermine the amendment’s only chance at passage. In reality, Lincoln had told the lame-duck congress that if they did not pass the amendment he would call a special session of the new Congress in March of 1865, made up of enough Republicans (elected that November) to easily pass the amendment.

Historian James Oakes, in his book Freedom National — The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, published in early December, suggests that Lincoln screenwriter Tony Kushner might have that part of the history right. Oakes points out that a large number of Republicans felt that the amendment abolishing slavery was a “civil” rather than “military” measure, and that the basis for changing the constitution was thus linked to the winning of the war. As the war’s end drew closer, the justification for the 13th Amendment was potentially undermined.

In an email exchange with me about his book and the movie, Oakes speculates that Lincoln and his Republican allies were worried that public support for the passage of the amendment would dissipate as the exigencies of war diminished. “If abolition were imposed AFTER [Oakes’s caps] the South surrendered it might seem vindictive to northern voters, or voters might think Republicans were liars or were disingenuous for having claimed that abolition was a war measure,” Oakes wrote. Although this argument does not appear in the film, it was a central theme for New York Congressman Fernando Wood, the Democratic attack dog in Congress and in the film.

What Oakes finds more troubling in terms of historical accuracy is the scenario set up by Kushner, whereby conservative Republicans (represented in the film by Montgomery Blair) and Radical Republicans had to be brought in line to defeat the Democrats and pass the amendment. Oakes points out that the Republicans were united all along, as demonstrated by the House vote to pass the 13th Amendment that took place the previous July. There was only one Republican “no” vote at that time, cast by Ohio Republican James M. Ashley. Ashley was a strong supporter of the amendment, but realizing the amendment was about to lose, he voted no as a procedural maneuver that would allow him to call for reconsideration of the amendment when Congress returned in December.

Blair, who had represented Dred Scott in the famous Supreme Court case, was Lincoln’s Postmaster General until he was replaced in late 1864. Blair had influence in Maryland and Missouri and was called upon to secure Border State Unionist votes, not to cajole conservative Republicans. Between July 1864 — when Democrats and Border State congressman had defeated the amendment — and January 1865, both Maryland and Missouri had abolished slavery. So Congressmen who had represented slave states the previous July were representing free states in January. They were the Congressmen that Blair went after.

Historians and journalists will and should continue debating the historical accuracy and limited context of the film, especially the invisibility of blacks as central participants in their own liberation.

In his blog, Brooklyn College Professor Cory Robin quotes from the 1992 book Slaves No More (by Ira Berlin et.al.), making it clear that despite Lincoln’s great accomplishment, historians overturned long ago a Lincoln-centered view of emancipation. The destruction of slavery was:

[A] process by which slavery collapsed under the pressure of federal arms and the slaves’ determination to place their own liberty on the wartime agenda. In documenting the transformation of a war for the Union into a war against slavery, it shifts the focus from the halls of power in Washington and Richmond to the plantations, farms, and battlefields of the South and demonstrates how slaves accomplished their own liberation and shaped the destiny of a nation.

The relegating of African Americans to secondary roles, even in films where black civil rights is the central topic (2011’s The Help is a recent example) is unfortunately the rule rather than the exception. But on the positive side, Lincoln has accomplished something that historian and literary critic Irving Howe suggested is very rare for American artists: the ability to portray politics as “a distinctive mode of social existence with manners and values of its own.”

The history of slavery, its origins, extirpation, and consequences, becomes more fascinating and illuminating once the context is expanded. Robin Blackburn’s new book The American Crucible — Slavery, Emancipation and Human Rights argues that the success of anti-slavery movements involved some combination of class struggle, war, and a re-casting of the state’s relationship to the claims of property — New York Congressman Fernando Wood, for instance, spoke against the 13th Amendment as a “tyrannical destruction of individual property.” Wood was pointing to the broader underpinnings of both the Constitution and state law.

For Blackburn, who writes in a Marxist vein, dominant economic interests, both North and South, needed a “different type of state.” In the South, slaves, who were legally property, could run away, while northern manufacturing demanded state regulation of finance, funding for internal transportation and communications infrastructure, and tariff protection. These Unionist and Confederate “rival nationalisms” were both expansionist, the Union looking to overtake the continent and the Confederacy eyeing new slave territory in the West, the South and in Cuba. The clash, according to Blackburn, “was thus one of rival empires, as well as competing nationalisms.”

Foner also places the state in the center of Civil War and Reconstruction history, focusing on how shifting political dynamics shaped the economic and social relations that followed the abolition of slavery. Slavery was a mode of racial domination but also a system of labor that a “distinctive ruling class” was fighting to retain. The “labor question,” and what role the state would play in re-constituting a disciplined and docile labor force after the Civil War became central to the battle between former master and former slave.

It was Radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens (portrayed by Tommy Lee Jones inLincoln), Foner points out, who recognized the “hollow victory” that liberation would bring unless accompanied by the “destruction of the land-based political power” of the agrarian ruling classes. In Nothing but Freedom — Emancipation and Its Legacy, Foner reveals some striking similarities between post-emancipation southern politics and similar developments in the Caribbean and Africa. Struggles over immigration, labor laws, taxation, fiscal policy and the definition of property rights “reveal how much of post-emancipation politics was defined by the ‘labor problem.’ In the southern United States, sharecropping became the common solution to an economic struggle whereby resilient planters and large landowners where eventually (after Radical Reconstruction) able to deny blacks access to productive land, capital, and political power.

If this seems a bit far afield from the central focus of Lincoln, it shows how difficult — how impossible — it is to present complex historical “moments” through film. History is not a series of “moments” but is, as the recently deceased historian E.J. Hobsbawn reminded us, something that surrounds us. “We swim in the past as fish do in water, and cannot escape from it,” Hobsbawm wrote in On History. The historian’s role — from Hobsbawn’s (and Marx’s) point of view — is the examination of how societies transform themselves and how social structures factor in that process.

Getting history wrong, as Ernest Renan noted over a century ago, is an essential element in the formation of a nation. Historians will continue to inform us about whether Spielberg and Kushner got Lincoln wrong in the service of polishing a national myth. Perhaps it is an unfair criticism to direct at a two and-a-half-hour movie on one of our most important political figures, but this story of emancipation is woefully incomplete. How could it be otherwise?

Tragedy very often accompanies politics practiced a high level. Has any American President avoided making decisions about the life and death of others? Lincoln was a man able to control his vanity by casting a cold eye upon both the virtues and the corruptions of human beings. He was able to reject cynicism, that reliable psychological shield for feelings of political impotence, and this the movie demonstrates clearly.

The film succeeds in portraying Lincoln as a political man in Weber’s sense, a man of ambition who was willing to be held responsible for the results of his decisions.

Moving away from the sterile debate over whether he was a “compromiser” or a man of “principle,” the film shows he accepted the fact that, in his political life at least, there would be a constant tension between the two.

Shares