There's a booming and rather dubious genre of inspirational book aimed at people who want to do something creative -- usually writing. (Rule of thumb: If you spend way more energy and time psyching yourself up to work than you do actually working, there's a serious problem with your approach.) Much rarer are those books written by and about the working artist; perhaps the best-known and most-cherished is Annie Dillard's "The Writing Life." To this select company we can now add David Esterly's profound and wondrous "The Lost Carving: A Journey into the Heart of Making."

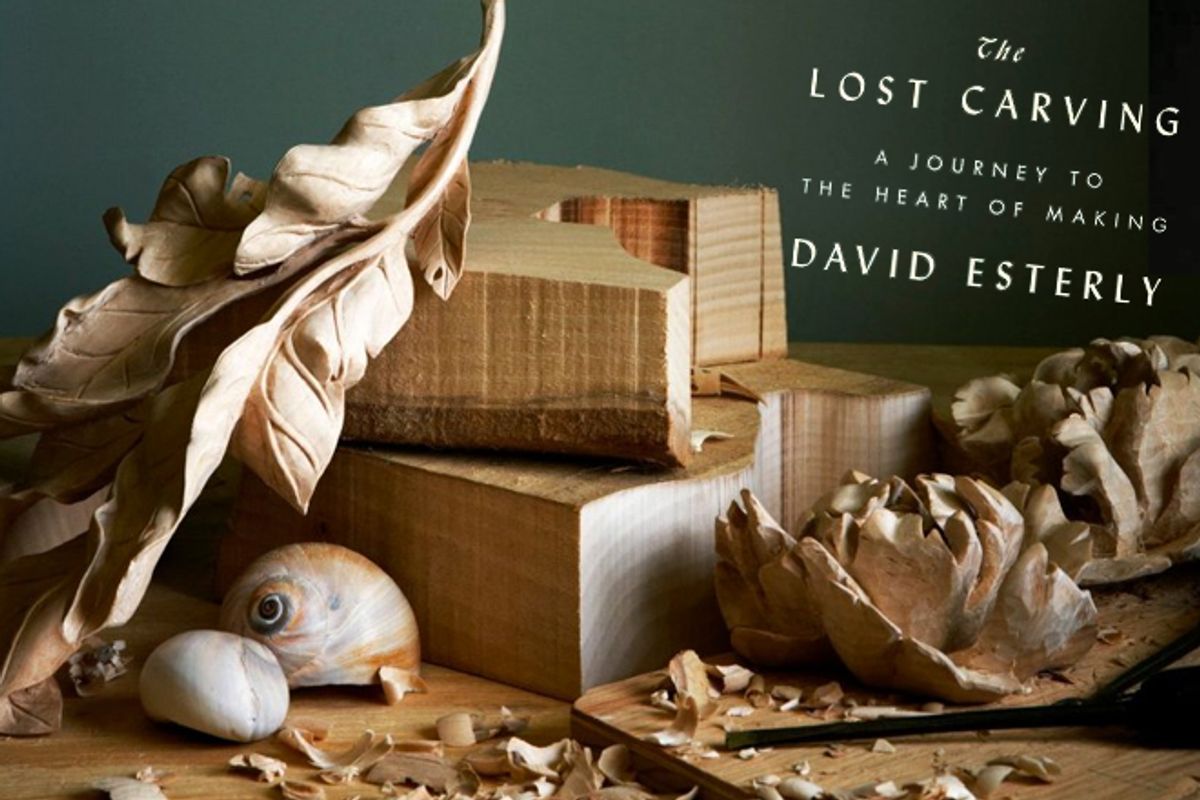

Esterly is that uncommon thing, a visual artist who can coax as much beauty from words as he can from his primary medium. The medium is wood, specifically limewood, a "charismatic" material noted for its creamy pallor and, among woodcarvers, for its "crisp and firm" texture and reticent grain. The great master of limewood carving was a 17th-century Dutch-born Englishman named Grinling Gibbons. His works adorn several London churches and stately homes, among them Hampton Court Palace, a royal residence in Richmond upon Thames.

Gibbons' trademark is elaborate, lifelike festoons and cascades of foliage and fruit, punctuated by the occasional cherub or bird. As a display of skill, he carved an astonishingly delicate "lace" cravat that Horace Walpole once wore around his neck to a diplomatic reception. Walpole also wrote, "There is no instance of a man before Gibbons who gave wood the loose and airy lightness of flowers, and chained together the various productions of the elements with the free disorder natural to each species." Gibbons was said to produce wooden flowers so fine that they trembled whenever a carriage rattled past his workshop.

One of the very few contemporary carvers to work in a similar vein, Esterly, an American, taught himself to carve after a revelatory visit as a young man to St. James Church in Picadilly, the location of one of Gibbons' major works. There, "floating on the reredos, the wall behind the altar, was a shadowy tangle of vegetation, carved to airy thinness ... I looked and my tongue seemed to be moving over carved ivory, cool and smooth. Don't ask. I haven't a clue. It's what I still feel in the presence of great limewood carving ... I was only an observer, but somehow it felt as if I were creating the object I was observing, creating it in the act of seeing it."

Up until then, Esterly had been alternately an literary academic and a laborer, swerving from studying Yeats and the Neoplatonic philosopher Plotinus at Cambridge to unloading beer trucks and boxcars in Ohio. He seized on carving as the ideal union of mind and body in a single, meditative activity. "Carving is a metaphor for everything," he writes. "What is abstract elsewhere is concrete on the workbench." The humility of the craft seems to suit him. "A carver begins as a god and ends as a slave," he explains in describing the process. "You start as a godlike creator, imposing ideas on a passive medium, and you end up grounded in the life of this world, taking instructions from the thing in front of you." (The wood's innate properties become "imperious" toward the finishing of the piece.) It is not only carvers who follow that trajectory, of course.

One work stands at the center of "The Lost Carving": a large Gibbons carving lost in a 1986 fire at Hampton Court Palace. Esterly was hired to reproduce it, a painstaking process involving the minute study of surviving companion pieces and photographic records, as well as heated debates over sandpaper and varnish. Entwined with the story of the year Esterly spent at work in the palace are an account of his self-guided apprenticeship in the English countryside in the 1970s (where he lived with his new wife in an underheated but picturesque cottage) and scenes from his present-day life in rural upstate New York. It's a complex structure, like one of Gibbons' intricately braided garlands, but pulled off with such fluidity that the feat is barely noticeable as such. "It's uncanny," Esterly observes at one point, "but the hardest parts to carve are the parts that end up looking as if they were the easiest."

Many of Esterly's insights on the act of creation are similarly aphoristic and paradoxical. Recounting a lesson he once gave in foliage carving -- in which he instructed his students to put aside their own personalities and strive only to convey the "essence" of a simple laurel leaf -- he found that the results were nevertheless wholly "individual," but in an "unconscious, unintended" fashion that was superior to any deliberate statement. "If you want to express yourself," he concludes, "stop expressing yourself. Better yet, stop wanting to express yourself." On discovering that Gibbons had "meticulously executed" portions of his carvings that would be invisible once the works were in place, he writes "Early on I discovered a curious thing about carving. Fifty percent of the effort will achieve ninety percent of the effect. Another discovery followed on quickly. If you allow yourself to stop at that ninety percent, then the carving can never really succeed."

For Esterly, such maxims are always derived from the tactile experiences and logistical challenges of tool and wood, and this keeps "The Lost Carving" from drifting off into the ether, a constant peril in writing about writing. Likewise, parts of the book recount his clashes with British arts administrators and curators over how Gibbons' carving ought to be restored (Esterly has much to say against the habit, established in the Victorian era, of staining wood brown) and his desire to mount an exhibition of the artist's work. These skirmishes and negotiations, too, are part of any professional creative person's life.

You'd think the ambiguous status of woodcarving, even the work of a master like Gibbons, would chagrin a high-minded practitioner like Esterly: Is what he does art or ornament, part of the interior design of the palace or a detachable, independent work like a painting or sculpture? Many would deem his carving merely artisanal, a craft, while placing "The Lost Carving" itself, a book rich in thought and lovely in style, in the category of art. Here, for example, is how Esterly describes the trials of working on a commission that called for a variety of hardwoods instead of his beloved lime: "The woods were rough and oversensitive at the same time. They existed in a culture of honor, where a request perceived as unseemly elicited a vicious response. Push them too far and they'd just split."

It would be impossible to separate the art of that metaphor from the craft that inspired it. The author doesn't bother to try; the distinction is, after all, as superfluous as striving to convey your own personality in the carving of a laurel leaf. The serenity of this indifference, Esterly's unfailing ability to focus on what really matters, is breathtaking. No doubt the artists (and aspiring artists) who will embrace this book, passing it on with fervent recommendations and christening it as the classic it deserves to be, will find as much learn from his example as from his advice.

Further reading:

Shares