Let’s call 2012 the year of the suicide: On Friday, the Department of the Army released a report revealing that suicides continue to outnumber combat-related deaths among American soldiers —an average of one suicide a day— a number that’s increasing despite the fact that the armed forces have installed new training and awareness programs over the past few years. Stateside, suicide has become the leading cause of death by injury, and is the 10th leading cause of death overall. According to a CDC report released over the summer, suicide attempts by high-school students has risen to from 6.3 percent in 2009 to 7.8 percent in 2011, and accounts for 13 percent of all deaths among people between the ages of 10 and 24 — the third leading cause of death in that age group.

These are sobering statistics. And with the statistics comes more data to explain them: The Washington Post reported that “the stress on the force after more than a decade of lengthy and multiple deployments for many troops in support of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan,” while Defense Secretary Leon Panetta attributed the high rate to “substance abuse, financial distress and relationship problems … that will endure beyond war.” Among civilians, the number of suicides have been attributed to the recession — historically, there is a spike with every economic downturn. And 20 percent of high-school teenagers say they are being bullied — 16 percent say they’ve been cyber-bullied through texting, IM-ing, email, and Facebook or other social media.

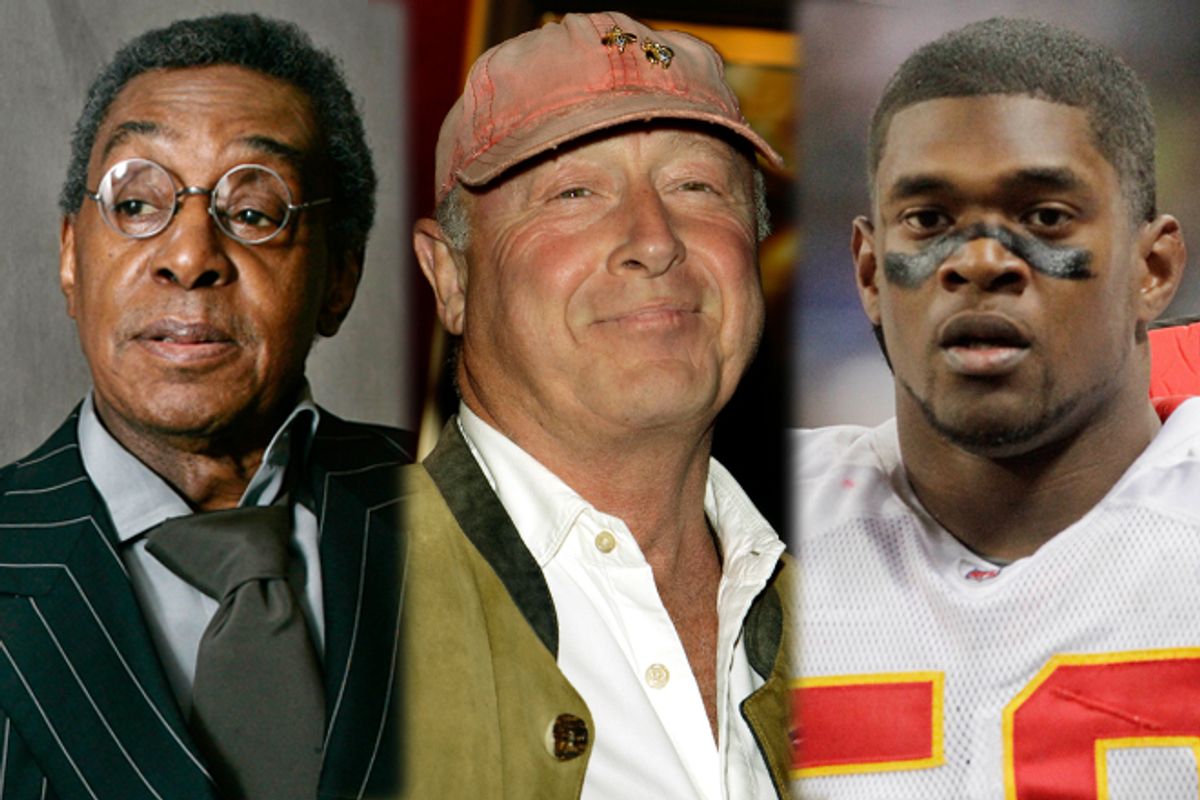

Though these stats may elicit sighs, we develop a kind of immunity to reading them because they’re so abstract — names are what humanize the story. And there were plenty in the headlines the past year, people we’ve admired from afar, or people we encountered because their suicides were so lurid. There were those who were said to have killed themselves to be released from physical agony, like “Soul Train’s” Don Cornelius, who battled unrelenting seizures from an aneurysm he’d had 15 years earlier, and Fleetwood Mac's Bob Welch, who learned he’d suffer lifelong excruciating pain from the spinal surgery he’d had three months earlier. Director Tony Scott jumped off the Vincent Thomas Bridge in L.A., and was initially reported to have had inoperable brain cancer — though an autopsy would disprove that report (there was no sign of cancer). There were those who decided to end their lives because they were overcome with psychic pain, like “Three Cups of Tea” co-author David Oliver Relin, 49, and 57-year-old visual artist Mike Kelley, who had been suffering a depression following a breakup. It’s hard to know what motivated the most violent suicides, those paired with murder: Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Jovan Belcher, who shot himself, after having murdered his girlfriend, and Adam Lanza, who killed himself after committing one of the most heinous mass shootings in history.

There are so many angles, so many ways to explore this subject (and the news, I’m afraid, will provide us with plenty of opportunities): Has suicidal depression become an epidemic? Is suicide ever okay? Is this the fault of our health-care system? Would gun laws prevent suicide? Why are more and more suicides paired with homicides — and massacres? Each of these demands a dissertation. I’m not a psychiatrist or a policy wonk or a statistician, so I can’t even begin to answer these questions.

So I won’t. Instead, I come to this subject with a question driven by something very personal, a question that is at once the simplest and most complicated one to pose: Why do some of us choose to die, and some of us, even the depressed among us, have the will to live? There was a time when I believed I understood why people committed suicide. Yes, I’ve laid out some reasons above, about people I don’t know. But those responses are soundbites, given to the press by family members and friends of the deceased, or shrinks called on by the reporter, spokespeople for the organization that reps the deceased, etcetera. And while there is some truth to what they say, the fact is, probably none of us knows what finally pushed them over the edge. That is the legacy of suicide, the worst possible thing about it — that all of the surviving friends and family are sentenced to a life of torturous wonder.

I think about the grieving parents of Rutgers freshman Tyler Clementi, who killed himself in 2010. They were granted a sense of closure earlier this year, when the state of New Jersey's Superior Court convicted Clementi’s roommate Dharun Ravi with 15 counts of crimes involving invasion of privacy and bias intimidation. The court’s ruling essentially gave the Clementis permission to believe that Ravi drove their son to kill himself. And indeed, Ravi was guilty of committing those crimes against Tyler Clementi, of creating a menacing environment. But was bullying what led Tyler to jump? It sounded plausible to me when the story broke. But then I read Ian Parker's piece in The New Yorker last February, and I started to think otherwise.

Like Clementi, I went to Rutgers — I began my freshman year there 22 years before he did. I have no connection to New Jersey, though: I’d moved from Chicago, with the express purpose of coming out, in private, away from everyone I knew, after learning that they had one of the first gay and lesbian organizations on campus. Our situations were very different: I was outgoing and lived in the cultural epicenter of campus — a hotbed of activism, of activity, of everything. Clementi was a shy kid, bunking in a tiny room on an annex campus, Busch, living in exile as a lone gay among the engineering and math and pharmacy students who were not known, as a whole, for being socially progressive.

But he and I shared one thing: We pursued same-sex romantic partners who were deeply closeted. And few things can make you feel lonelier than not being able to enjoy and share love; what’s worse, contending with the mercurial temperament of a person terrified of exposure. It can match, if not exceed, the terror of being bullied: The threat of being dumped, of having to go through a breakup alone, can be more than enough to exacerbate any depressive's sense of despair. I remember it well, because in those moments when my relationships threatened to come undone, my brain would feel like it was spinning off its axis, and my mind would switch into suicidal ideation mode, like a default, and my mood would plummet from elated to absolutely wanting to die.

But, something, I don't know what, kept me from acting on my impulses: Instead, I’d call Lisa, my first friend at Rutgers, the one person I trusted to keep a secret, who happened to be the same person who could talk me out of it. According to Ian Parker’s New Yorker feature, Clementi, sadly, reached out only to people he’d met on a gay porn site, friends he’d never met in person. Which led me to imagine his thought process, based on my own: Following an argument with the lover, he’d become wholly absorbed in his toxic thoughts, fully rapt, even if momentarily, by his excruciating pain. But here’s where he and I would diverge: He’d snap and lapse into a fatal insanity that ultimately would propel toward the George Washington Bridge. And then ...

Though it doesn’t matter what I imagine happened to Clementi. Because now I’m as guilty as any survivor of the dead, yearning for that closure, trying to create a linear narrative to make sense of the illogical — it’s what distinguishes the insane, murderous moment from the rational. But I do recognize those flashes of intense self-hatred that devolve into despondency. Fortunately, I never broke — in part, I like to think, because I was lucky enough to have a friend like Lisa. If only Lisa could have instilled in herself the same life-affirming message she instilled in her friends.

Three years after college graduation, I was in the grips of one of my most acute depressions. Unbeknownst to me at the time, so was Lisa. I’d returned home from an evening out with a friend, after having spent much of the week in bed, when I’d gotten a message that Lisa had hung herself. She was the last person I’d ever have expected to die by her own hand. In school, she was vibrant and brilliant, the friend from whom everyone sought advice (not just me) the friend who threw the most amazing dance parties — the friend who was, well, everybody’s best friend. But soon after we graduated, she developed an ailment I could only describe as a psychic cancer. I realize now, in retrospect, she was likely in the early stages of battling bipolar disorder, and after her second bout of a very intense, nearly catatonic depression, she killed herself, leaving behind people who would have done anything to save her: her fiancé, her parents, her older sister, and so many friends.

In the weeks after her suicide, I’d learned that she’d been very forthcoming about her suicidal ideations. In a way, it was hard not to see her incapacitating depression as a terminal illness, I rationalized, so why not forgive her for it the way we forgive stage-4 cancer patients for assisted suicides? I remember getting into it with my mother, who said suicide was the ultimate fuck you. “Well, that doesn’t apply to Lisa,” I barked. “She’s not an aggressive person, and she’s not a vindictive person!” And she wasn’t, not in the least. It wasn’t about hurting other people. It was just about hurting. I would say repeatedly, “I totally get this, I get why she did this.”

But in the years that followed, I saw how much it had hurt other people, especially her family: Her mother never recovered, and followed in her daughter’s footsteps eight years later. Which makes me think about the surviving families and friends of the soldiers and the football players, the teenagers and the luminaries: Maybe they have found a satisfactory answer, or maybe they saw it coming. But are those answers enough to stanch the grief? Or quiet the taunting, repeat-play interior monologue that asks whether something could have been done to stop it?

Now that I’m a 42-year-old mother, nearly 20 years after Lisa’s death, I admit: I no longer “get this” — and it terrifies me more than ever, as I cuddle with my toddler, who is walking and starting to talk and doing all the things 15-month-olds do. Because I think about the joy her parents must have felt in having two healthy, beautiful daughters, who thrived at school and in life, and I wonder, how does this tragic story fit in? It doesn’t. But it is their story now, and it tore apart a wonderful, loving family.

I can think of reasons — good reasons — why Tyler Clementi may have committed suicide. And Don Cornelius. And Tony Scott, and Jovan Belcher. But are those reasons the reason? Why wasn’t someone like Lisa able to carry on, and why is someone like me, who had been so outspokenly depressed, alive? I honestly have no idea. I can only say I’m grateful to Lisa for helping me stay here, even as I grieve for her, and for every single person who can’t bear to live another day.

Shares