I left Ghana, returned to New York, and got married. Victor and I had a joyous ceremony of twenty close family members at an Episcopal church in Washington Heights across the street from a bus station overrun by drug addicts. Together we bought a run-down one-bedroom apartment, joining our possessions, our hang-ups, our dreams. After moving in I forgot about my travels for a while. Maybe I hadn’t found the Promised Land, but what I did have seemed pretty damned good. We settled into a comfortable life. It was because of this comfort, precisely because I’d stopped actively seeking, that I encountered the man who would lead me on my last pilgrimage. That man’s name was Creflo Dollar.

It was Victor who introduced me to his program. I myself didn’t usually stay up so late. Slouched on our thrift store loveseat in the middle of the night we’d sleepily flip through the channels during commercial breaks of Victor’s favorite, "Headbangers Ball," or long after the curtain call of "Saturday Night Live," and happen upon the stocky black televangelist prowling the pulpit. As Victor put it, the man knew how to fill a custom-made suit, and he wasn’t above telling you how much the suit cost. In fact, Pastor Dollar considered his material wealth — the private jet, the Rolls Royces, the mansion in Atlanta — points of pride as reflections of God’s blessings upon his life. He was fond of mentioning that many of these possessions were gifted by members of his flock in gratitude for his deliverance of the prosperity gospel, a belief that God’s devout followers will be successful in all endeavors, including financial matters, as an expression of His favor. How this success was meant to be achieved wasn’t entirely clear, but it seemed to involve being born again into the faith and tithing considerable sums of money to Creflo Dollar Ministries.

His sermons often invoked the story of Exodus. “The Lord kept the children of Israel alive in the wilderness for forty years. He nourished them with the blessing of sweet manna from heaven. He wanted them to have plenty so they could be a blessing, just as He wants you to have plenty.” This was the crux of the prosperity gospel — God did not intend for His chosen people to suffer, but rather to have plenty, to be full, to be spiritually and materially rich. The way Dollar used the myth of Exodus, which has sustained and unified black people through times of suffering since the days of slavery, was so far beyond crass that it had to be a farce. God’s plan for us is to drive a Bentley? And we will attain it by giving 10 percent of our salaries to this huckster? Really?

Members are encouraged to tithe with automatic bank account withdrawals managed by World Changers Church. Fellow Atlanta ministers, who preach in the humble tradition of Reverend Martin Luther King, rib Dollar for commercializing Christ. “Pass-a-Dollar,” they call him. “Cash-flow Dollar.” But Victor encouraged me to consider the preacher’s appeal.

“You’ve been trotting all over the globe searching for Zion. But if you want to know what Zion is for black America here and now, then you need to pay attention to this guy,” he said.

“Why? What’s his platform?” I asked. “Obama Wants Change, We Want Dollars?”

“Uh, uh. It’s capitalism, baby. Plain and simple. The American Dream.”

I sputtered something about the integrity of the black church. I’d no doubt read it in one of my father’s books about suffering and salvation. This was a topic I understood, not from having grown up in the black church myself, but through my Catholic upbringing and my father’s intellectual lens. Christianity, as I knew it, was a religion of suffering. At the heart of the Christian tradition was the agony of Christ and the martyrs. Personal suffering bound the Christian to the suffering of the world. Faith and affliction were two sides of a coin whose worth nobody knew better than the slaves of old. According to my father, “the primary example of suffering Christianity in this country was the experience of African-American slaves.”

By shilling money as the thing that mattered most, men like Creflo Dollar, I complained to Victor, were cheapening our rich history of liberation theology, messing with the prophetic kind of faith that drove the Civil Rights Movement, our nation’s proudest moment. My father taught a seminar on the religious history of that movement and these were themes he’d discussed with me for as long as I could remember. He’d grown up during that ennobling period. He was nearly the same age as Emmett Till would be if he hadn’t been bludgeoned to death and dumped in a Mississippi river at age fourteen for talking to a white woman. This was the backdrop against which my parents met at a Catholic university in Milwaukee in the 1960s. There my father helped organize a student movement that pushed for more minority faculty hires and student enrollment. Along with two roommates, he led a protest that shut down the university for two weeks.

Perhaps, like many children, I had a romance with the time of my parents’ youth. Their heroes were Martin Luther King and Dorothy Day, whose Catholic Worker offered a moral critique of the country’s drive for wealth and comfort. Wealth was a spiritual hazard that flew in the face of social justice. And didn’t my hero, Bob Marley, say more or less the same thing? A belly could be full yet hungry. A full stomach didn’t ensure a full heart or a full life.

But Victor only laughed. “What’s so funny?” I asked him.

“Darlin’, I love you. I do. But you have the most convoluted way of trying to know your father.”

“I’m not talking about my father,” I insisted. “I’m talking about the problem of Creflo Dollar.”

“Okay,” Victor humored me. “Why should black people be holier than anyone else just because we’ve suffered? Why shouldn’t we want the same comforts everybody wants, in the end? A mortgage, a car, a retirement plan?”

Victor was the son of an African immigrant and had an immigrant’s sense of optimism about this land and its possibilities. His mother made us play the Mega Millions lottery because she believed we might actually win. I was the daughter of a black man who’d literally and figuratively lost his home. I’d inherited this sense of loss along with his sense of destiny. But in spite of our differences, it wasn’t lost on me that Victor made his point around the time we’d just signed our mortgage. We were not sufferers ourselves, not by a long shot. We were emissaries from the place the Rastas called Babylon Kingdom and we were free to travel anywhere in the world we desired. We were so liberated that we were practically dilettantes. Maybe it was time to let go of the old romance with suffering, to begin another narrative.

I began watching Creflo Dollar “Tell-a-Vision,” at first as a skeptic and out of morbid curiosity. What had changed so drastically since the civil rights era that a major arm of the black church now saw Zion as a financial realm? What was liberation for? Was it simply to fit into the comfort and ease of consumer culture? I tried to put these questions to Dollar directly, but my attempts to reach him were as much in vain as the Rastas trying to communicate with the queen. I got as close as his public relations person, who brushed me off by saying he was a very busy man. Dollar was probably savvy to be guarded about granting interviews. His ministry was under investigation by a Senate committee for fraud.

Creflo Dollar’s church attracts some forty thousand members, most of them poor and working-class blacks trying to pull themselves out of poverty and into the middle class. They’re drawn by Dollar’s lavish lifestyle, his optimism, and his instruction of the Bible as a manual for prosperity. We are in control of our destiny, he teaches. We are already in the Promised Land. This is our home. We built it. It is ours.

Soon enough, I, too, was mesmerized. More than that — I was hooked. Beneath the mustache, thick as a Band-Aid, the smile had a blinding wattage. The big teeth didn’t look natural, and neither did his perfectly even hairline. His linebacker’s shoulders were a holdover from his college days as a star football player. You don’t build a ministry that takes in seventy million untaxed dollars a year from tens of thousands of members worldwide without charisma. Even after Victor fell asleep on the loveseat, I kept watching deep into the night, held by the flickering blue light of the ridiculously oversized flat-screen TV before us, trying to unravel Dollar’s message.

As a preacher, his trick was the power of positive thinking. As a motivational speaker, his trick was the Bible. As CEO, his trick was a wily concoction of both: self-help and Jesus Christ. It was a winning combination. Dollar’s product almost couldn’t lose, and his delivery was pitch-perfect. He was plainspoken, corporate, encouraging. He could sound like a Holy Roller and Oprah Winfrey in the same breath: “Get lack and insufficiency off your mind,” he urged. “Get satisfied. The Lord shall increase you more and more. I believe that when you get increase on your mind, you’re gonna receive increase in your life, and when you sow and give into the kingdom of God, it will trigger increase. Pray about sowing into this ministry and experience increase. It’s time to reap your crop.”

I was remarkably drawn to this snake oil salesman who used increase more often as a noun than a verb. A lot of what he said made sense. Just as he could sound like the Bible-thumping Pentecostal preacher Oral Roberts, whom he counted as a close friend, he could also sound like the black nationalist Malcolm X, who criticized the docility of the black church. Against my better judgment, I got sucked into a Black Entertainment Television wormhole — I followed Dollar’s show religiously and then began watching other black televangelists too. These men were slick. There was Bishop Eddie Long, whose Georgia mega-church pulled around twenty-five thousand members, and T.D. Jakes, with about thirty thousand in Texas. One night Jakes recounted a visit to a Johannesburg museum where he encountered a proverb on the wall: “When the Dutch came, we owned the land and they had the Bible. When they left, they owned the land and we had the Bible.” He asked his congregation one vital question: Why couldn’t they have both?

“We should be able to hand our children more than our religious tradition,” Jakes argued. “Our faith has been a blessing and a curse. It stabilized us in times of adversity. Where would we be without our faith when we had nothing else, when we were being beaten and raped and killed and murdered? What disturbs me about our faith as we were taught by our slave masters was to make us hope for heaven while we lived in hell on earth. There ought to be a way we can hand to our children more than our religious tradition. We can hand them a home, hope, a degree, and then use the faith to fuel our dreams rather than to anesthetize our disappointments.”

I thought his words important enough to copy in my notebook. Creflo Dollar and Bishop Long preached the same hopeful message, in slightly different ways, but Dollar remained my favorite sermonizer. He was the best showman, which is probably why his World Changers Church had the longest reach, with offices in South Africa, Nigeria, Australia, and the UK. I visited its New York branch in order to see Creflo Dollar deliver the good word in person on Fat Tuesday, the night before the start of the Lenten season.

Down in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, where my father was from, it was Mardi Gras. I didn’t know if or how his people, who’d been displaced by Hurricane Katrina, were celebrating tonight, but I can tell you that the congregation assembled at World Changers Church, New York, was reveling. Not because tomorrow, Ash Wednesday, marked the start of forty days of deprivation and they wanted to let loose but because they hoped tomorrow might be the dawn of their abundance and they wanted to give thanks. In fact, it was the second night of a financial empowerment seminar. Creflo Dollar had flown into New York from Atlanta on his Gulfstream III private jet to lead the service, as he does every Saturday, at a rented theater inside the Manhattan Center on Thirty-fourth Street. Across the street, at Madison Square Garden, Marcus Garvey had preached redemption to a crowd of twenty five thousand, ninety years before. In terms of egotism, star quality and the lure of black capital, Dollar seemed to have taken a page from Garvey’s book.

This is the Gospel of Wealth:

A line of shiny buses from New Jersey stand outside the theater when I arrive. With the efficiency and practiced cheer of an airline steward, an usher hands me a prepackaged communion wafer and tiny foil-topped plastic cup of syrupy wine along with a powder blue collection envelope before escorting me to an empty seat. The place is packed all the way to the topmost of four balconies and almost everybody is black. There is a buzz in the air. The woman next to me introduces herself as Gladys. She wears a nurse’s uniform and tells me she’s come directly from her work shift, just as she’s done for a year of Saturdays, in order to get out of debt, praise the Lord. I watch her stuff a hundred-dollar bill into her collection envelope and lick the flap. I wonder how she’s going to pay for groceries.

The lights dim and the navy blue velvet curtains rise on the stage to reveal a thirty-member choir and two jumbo screens on which, after a chorus of hallelujahs, an image of a Wall Street sign and the American flag fades into the testimonial of an attractive, young, light-skinned woman with chandelier earrings and a burgundy weave. Her earrings twinkle as she confesses, “They shut down my credit on Black Friday but the next week, because I sowed in the faith, I experienced increase when God forced my boss’s hand to give me a raise.”

“Tell it!” shouts Gladys, waving her hand in the air.

The stage lights come up on Creflo Dollar, standing behind a Plexiglas podium in a pin-striped suit over a lemon-yellow shirt. He’s in his late forties but has the chipmunk cheeks of a child. A hush spreads over the rented hall.

“Ain’t nothing blessed about being poor,” Dollar intones.

That’s right!

“The poor man’s poverty destroys him. Satan is the enemy trying to convince you that prosperity is a curse. Satan has frightened people into believing there’s something inherently evil about money. He’s spreading lies. He wants you to believe poverty is noble. Millions have been taken by his deception. I don’t agree. Can I get an Amen?”

Amen!

“Let’s look at some urban legends. There’s an urban legend that my real name isn’t Creflo Dollar but Michael Smith. That there’s ATMs in our church. That you have to show W2 forms to get into our church. So ridiculous. Satan’s spreading lies. There’s an urban legend that I’m stealing from my parishioners. Poor-minded, broke-minded church folk are contained in a prison of Satan’s making to keep them that way, fearful of a preacher named Dollar who will take your money.” He shakes his head, as if this pains him greatly. “When I came to you I came loaded already. You don’t need a board to determine the preacher’s salary. I’m proud to say I haven’t taken a dime from this church. To run for public office would be a demotion. I work for the King of Kings.”

Bless us, Pastor!

“Jesus is abundant. The question you need to ask is, ‘How do I as a believer gain access to his resources?’ Can you tell I’m getting ready to operate on you? If you have a poverty spirit in you, I will drive it all the way to Queens! The most powerful spiritual force the devil has ever had to battle will be the church alive to God’s purpose for prosperity. I am here to tell you, the farmer that plants a seed gets a harvest. My point is pretty clear: that you prosper.”

The scriptural basis for the doctrine of seed faith, generally credited to Oral Roberts, is the parable of Jesus in Matthew 4. Just as the sower plants seeds that reap a thirty – a sixty – or a hundredfold return in the biblical story, the believer who gives an offering in church can expect a return on their investment. Dollar’s innovation to the “seed-time and harvest” principle is that this act of devotion is a way to get out of debt. Before his lesson, a collection is taken up. I am accustomed to passing a basket, but at Dollar’s church, they pass buckets. I am also more familiar with the verse in Matthew 19, where Jesus says it’s harder for a rich man to enter Heaven than for a camel to pass through a needle’s eye. It’s startling how quickly the buckets fill. I don’t want to think this is just vulgar materialism, or that Dollar is ripping them off, but instead that they are paying for sound practical financial advice.

Then again, I am a seeker. This makes me susceptible to gurus, cults, and quacks.

When Dollar starts instructing us in the twelve steps to recession-proof our lives, everybody pulls out a notebook and joins me in taking notes. The first of the twelve steps is “I know my God will supply my needs. Not the government and not the state.” I worry about a platform that encourages us not to expect or demand anything of our elected officials, but the second step accords with me more: “I refuse to fear when circumstances seem to indicate failure.”

Fear, Dollar tells us, is Satan’s spirit holding us in an unsettled state from which we might be delivered through God’s true desire for us to experience heaven on earth. He wants us to stop listening to Satan whispering negative thoughts in our ear. He doesn’t sound so different from my yoga instructor when she tells us during our meditation practice to block the distracting chatter of monkey mind. It’s a different vocabulary, but the effect is the same. I have paid as much as twenty dollars a yoga class for the same lesson.

“I believe the spirit of God is gonna jump on you in public spaces such that you can’t hide it. You can’t leave ’til the benediction’s given. Every head bowed, every eye closed. You ready, now?” He softens his voice. “Trouble don’t last always. God will prosper you.”

At the end of the seminar, we pour out of the theater feeling refreshed, renewed, rewarded. And although I’m more than a little embarrassed to admit to my father how I’ve just spent the beginning of Lent, this is the revelation I share with him later that night on the phone right before he drops the bomb that he has cancer.

I feel the prepackaged body and blood of Christ rise in my throat. I swallow it back down. I have forgotten to eat dinner. My stomach twists like a rag. My heart speeds. My heart. My muse. My muse is dying, is going to die.

It’s not aggressive, he assures me, it’s slow growing and unlikely to be the thing that kills him in the end. Still, he’s feeling dark and drained enough by the diagnosis to have decided not to go on a class trip he’s planned with the co-teacher of his seminar on the Civil Rights Movement over spring break. He’s made the same journey across the Black Belt before, so-called for the dark soil tilled by dark hands on the plantations. Birmingham, Selma, Montgomery, Atlanta. It won’t be a loss for him personally to opt out. It may even be redundant for him to go again. On the other hand, he’s not been down South since the flood. I know he’s still depressed by Katrina, the cataclysm that has scattered his people all over the map. I believe both of these dilemmas, cancer and Katrina, are compounding to keep him off the bus. Because I’ve just returned from Creflo Dollar’s church, I feel a desire to experience what I imagine is a less materialistic version of faith. Something with the power to cure. Say the names of those cities to yourself — Birmingham, Selma, Montgomery — and try not to conjure the mythic struggle for civil rights, the opposite of the prosperity gospel. I knew what might wash the taste of Creflo’s cheap communion wine from my mouth. The South. Immediately, I volunteered to go in my father’s place.

The class trip coincided with Holy Week, the final days of the season of Lent. As a Catholic child I’d been instructed to give up a vice for Lent, such as thumb-sucking, back-talking, fingernail-biting, or eating candy. Almost always, these were sacrifices of the mouth. I knew the practice was supposed to bring me closer to Jesus, who spent forty days fasting in the desert, but that closeness seemed so abstract a reward. At the time, I would have preferred a sticker. Sometimes I got an Easter hat with a ribbon, which at least I could wear on my head. I hadn’t given up anything for Lent in twenty years, but now I felt the pull of tradition. During my tour of the South, I committed to giving up the negative thoughts about my father’s illness until we knew more. Under the influence of Dollar, I refused to fear.

In commemoration of the long-winded battle of civil rights, our tour would make several stops. It would conclude on Good Friday in Atlanta, the birth and resting place of Martin Luther King; Atlanta, which, according to the last census, had surpassed Harlem as America’s black Mecca; Atlanta, home of Creflo Dollar’s mega-church and the city to which some of our relatives had fled after the storm. After a week visiting the historic sites of civil rights, I planned to spend the morning of Easter Sunday in Atlanta under Dollar’s dome. I would confront the man in his own house. The rest of the holiday I would spend with my cousins.

In the wake of the flood, and the infrastructure that failed them, I wondered how our people conceived of the Promised Land that Martin Luther King spoke of. Was it a lost dream or something to keep striving for? Had any of them prospered, as Dollar preached was their right? Where was home now? With these questions in mind, I kissed my husband good-bye, packed my camera, and boarded the bus.

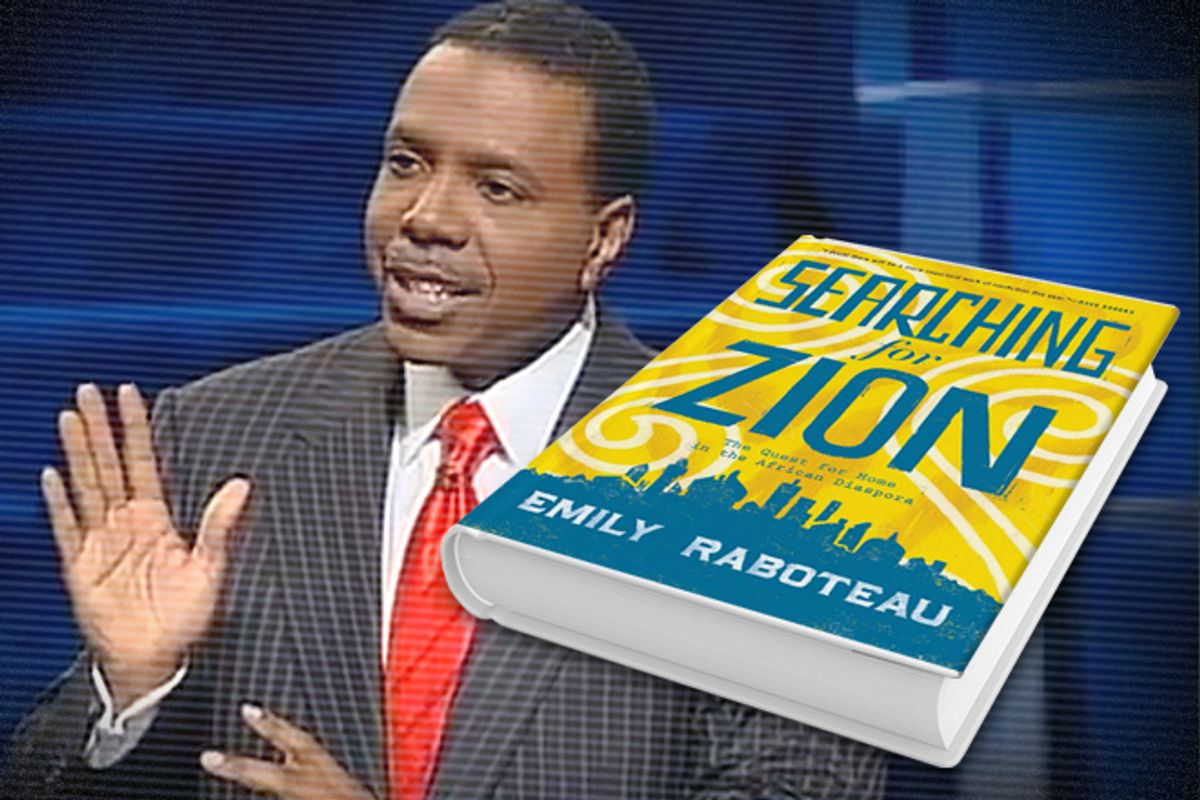

Excerpted from "Searching for Zion: The Quest for Home in the African Diaspora." © 2012 by Emily Raboteau and reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

Shares