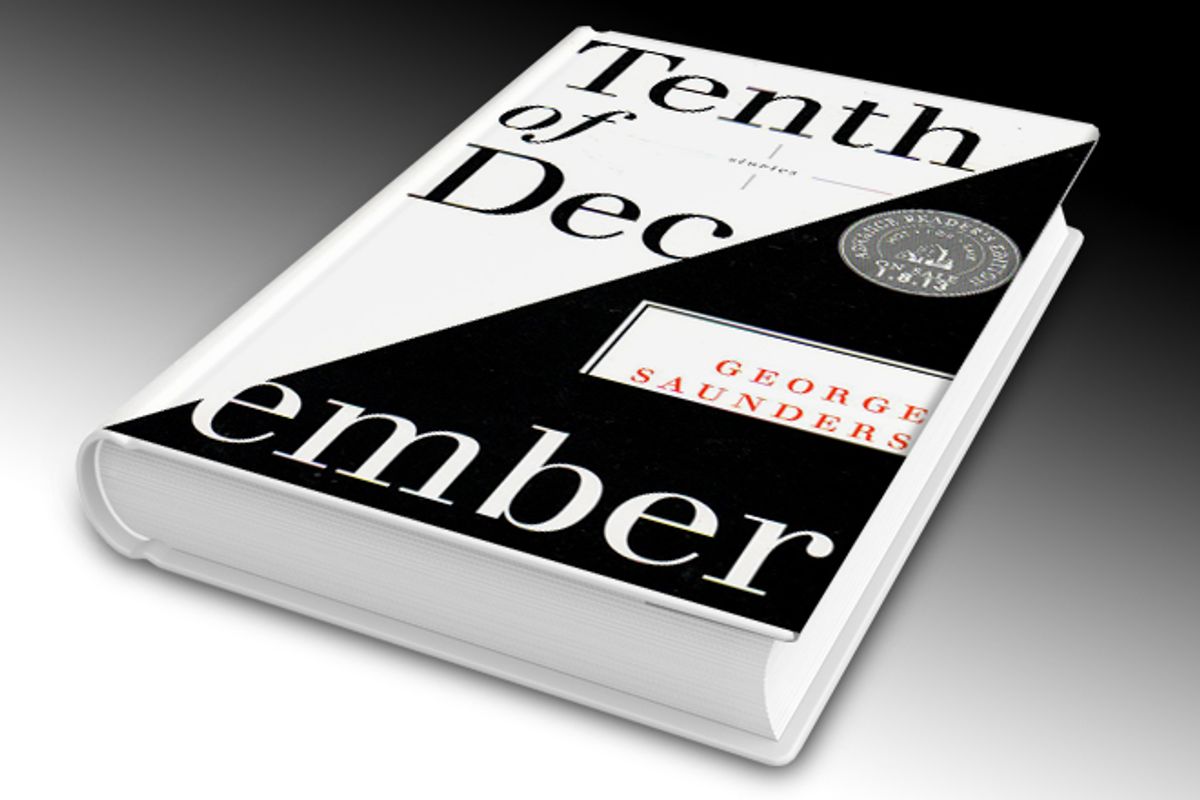

There is a genre of short story that specializes in exquisitely sketched, watercolor-subtle depictions of the desperation of the human condition. George Saunders does not write that sort of story. In the first place, his work does not consist of what is conventionally regarded as beautiful prose. To quote you a passage, from one of the pointed and affecting stories in "Tenth of December," Saunders' new collection: "So her mother could go right ahead and claim that she was spoiling the kids. These were not spoiled kids. They were well-loved kids."

No one is likely to cite that as an approximation of poetry, goading us to see the world afresh -- although, banal as it is, in the story that encompasses it, the passage is replete with meaning. I think of Saunders as a very distinctive stylist, to the point of being instantly recognizable, but to prove it, I can't deal out a handful of fetching sentences and metaphors like cards from a pretty deck. As penetrating as Saunders' stories almost always are, they don't do it by the sentence. Not a single line from them can even begin to work on its own, extracted from the tissue that gives it its potency. These sentences aren't beautiful, but what they are is true -- and just about the best possible rejoinder to Keats' declaration that the two things, truth and beauty, are equivalent.

Saunders is also not (necessarily) a realist. At least one story in each of his collections is set in a grotesque historical reenactment theme park, where the narrator is hired to pretend to be a reductively conceived figure from the past. In "My Chivalric Fiasco," from this collection, the narrator gets promoted from janitor to "Pacing Guard" at a "Fun Spot" in some kind of Medieval-themed operation. The new job is a reward for keeping his mouth shut about the boss' sexual assault on a female employee. Pacing Guard, however, turns out to be a "Medicated Role," requiring that he take a drug called KnightLyfe®, which causes him to speak and think in a genuinely chivalric fashion -- and thereby to ruin both his own life and the victim's.

In another story, "Escape From Spiderhead," a convicted killer agrees, in lieu of imprisonment, to be a subject in a serious of experiments. He and his fellow subjects are administered drugs that make them more articulate, more obedient or more appreciative of natural beauty, as well as a drug that causes them to fall in love (and then out of it, when the drug wears off). In "The Semplica Girl Diaries," a suburban dad struggles to supply his family with all the accouterments of affluence, including a type of lawn ornament made from living women, recruited from the developing world. The plight of these Semplica Girls troubles one of his daughters. ("Note to self: talk to her, explain it does not hurt, they are not sad, but actually happy, given what their prior conditions were like; they chose, are glad, etc.")

These stories are often funny, in an excoriating fashion, but they so easily tilt into horror that their claim to the status of satire can be perilous. While some critics have complained that Saunders' work hasn't evolved much, that's not entirely fair. The historical reenactment theme has been surprisingly consistent, but over the years it has graduated from idée fixe to trademark, like Bruce Springsteen reprising "Born to Run" at a live concert. Nobody does it better. Many of the stories in "Tenth of December" reflect Saunders' growing interest in stream-of-consciousness narration: "Victory Lap," for example, alternates between the viewpoints of a sheltered, sparkly-princess teenage girl and her neighbor, a boy whose life has been regimented to a fare-thee-well by his creepy parents. But in contrast to most stream-of-consciousness fiction, the technique itself is not the purpose of the piece; instead, Saunders wants to illustrate the relative inadequacy of each family's chosen method of indoctrination when their children are faced with an existential threat.

As a rule, Saunders' characters are downtrodden: wage slaves at a sinisterly vague enterprise instructed by their supervisor to keep up their "numbers" and "not to dissect every single thing we do in terms of ultimate good/bad/indifferent in terms of morals" ("Exhortation"), a failing small business man clinging to the shreds of the success gospel ("Al Roosten"), or an Iraq War vet whose mother is being evicted ("Home"). Their minds are colonized by kitschy scenarios derived from advertising, bad television and self-help books ("When will I have sufficient leisure/wealth to sit on hay bale watching moon rise, while in luxurious mansion family sleeps? At that time, will have chance to reflect deeply on meaning of life, etc., etc.")

In counterpoint to these flimsy tableaux beats the drum of life's catastrophe: illness, unemployment, poverty, ungrateful kids and unfaithful spouses. The classic trajectory of a Saunders protagonist is toward the point where the tension between whatever late-capitalistic propaganda they've ingested (or are trying to ingest) and life itself becomes untenable. Up to that point, the nostrums and doublespeak of their corporate overlords as imagined by Saunders have a savage humor; beyond it is vastation, and a brief opportunity for the characters to assert their dignity, however quixotically.

For some readers (count me among them), such stories are more than enough; it's not like anyone else is doing this, or at least not so masterfully, and collections from Saunders do not exactly pour forth. (This is his first in six years.) Commodification, dehumanization, exploitation -- all those -tions that sound so abstract but feel so brutal when you're in their teeth -- have always been with us in one form or another, and their current guises are well worth fictionalizing. But some of the stories in "Tenth of December," including the title piece, concern problems we consider eternal and impossible to parody, from cancer to sexual violence, if that's the material you prefer. As Saunders' characters, those fragile troupers, square off against a merciless universe, it's their courage, more than any metaphor, that makes them beautiful.

Shares