Steven Spielberg read aloud private emails from Daniel Day-Lewis -- in which the actor repeatedly declined to take the role of Abraham Lincoln. James Gandolfini went blue, as old-time comedians used to say, detailing the effects of drug addiction and an outbreak of diarrhea on a film production. (It was a hypothetical case, he said.) Michael Moore and Chris Rock both faced bizarre heckling from an apparently inebriated audience member; Rock ignored him while Moore, a one-time Roman Catholic seminarian, responded by quoting from the traditional Latin Mass. A few minutes earlier, I had heard Moore offering his unqualified support to Kathryn Bigelow and her controversial film “Zero Dark Thirty.”

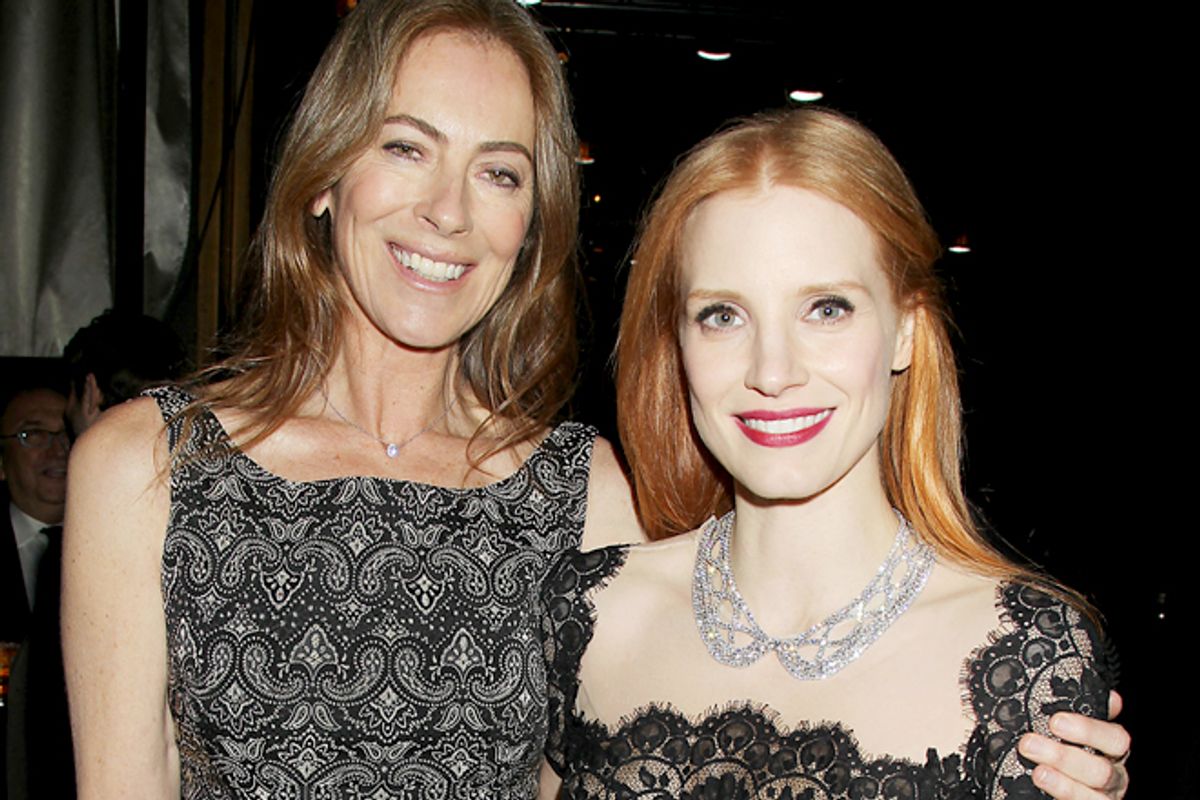

Tony Kushner, the Pulitzer-winning playwright and screenwriter of “Lincoln,” delivered a blistering, hilarious, fast-paced monologue worthy of one of his characters. Matthew McConaughey, always so confident on-screen, seemed to get lost in his own personal ruminations about acting and family life, revealing his limitations as an extemporaneous speaker. On the other hand, Bigelow began by saying that public speaking was not her métier, but went on to deliver an elegant theoretical defense of “Zero Dark Thirty,” saying she was grateful to be in a “room of people who understand that depiction is not endorsement, and if it was, no artist could ever portray inhumane practices.” As for her unwillingness to discuss her specific intentions, she joked, we had to remember that she came from the visual art world, where the goal is always to obfuscate rather than explain.

Those were among the highlights of the 78th annual New York Film Critics Circle Awards ceremony on Monday night, which packed an assortment of top-tier Hollywood talent into a relatively intimate Manhattan supper club. Since the winners were announced weeks ago, there was no Oscar-style suspense; the point of the annual NYFCC gathering is to serve as an early bellwether of awards season and also to give the downsized and embattled film critics of the nation’s media capital a chance to mingle with the entertainment industry’s big names on an informal basis. While the invitation-only event is on the record, no video cameras are allowed and no time limits on speakers are enforced – much to the detriment of McConaughey and of Charlie Rose, who rambled through a lengthy speech introducing the makers of “Zero Dark Thirty,” this year’s best-picture winner, without saying much of anything.

In this friendly setting, Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal came as close as they ever have to directly responding to their critics in the Washington establishment and the liberal media. In case you’ve been holed up in your own Pakistani compound for the last few weeks, various commentators and politicians have suggested that “Zero Dark Thirty” endorses the use of torture and argues that it was a fruitful tactic in the hunt for Osama bin Laden. As I and others have repeatedly insisted, those are different questions, and the way the film approaches them is deliberately murky and subject to interpretation. I feel confident, however, that Bigelow and Boal did not intend and do not hold either of those positions.

I was talking to Bigelow and Boal just before the ceremony started when Michael Moore came up to congratulate them. I won’t try to recreate extended quotes from memory, but Moore praised “Zero Dark Thirty” both as storytelling and cinema, and told them he thought many liberals had misinterpreted it. He had recently seen the film with his wife, he said, and they “got it.” It’s “the story of what happened,” he went on, but not a story intended to be read as literal, blow-by-blow journalism. That ambiguity, he suggested, had engaged a tendency among many liberals to leap to conclusions and resist deep thinking. Moore then wondered whether the three United States senators who had written a public letter complaining about the film – Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., Carl Levin, D-Mich., and John McCain, R-Ariz. – had actually seen it. Boal smiled and said he might be willing to continue that conversation in a different context.

Bigelow told me she had been taken aback by the forceful and negative response to “Zero Dark Thirty” from so many on the left: “We were really surprised by that. We certainly were not expecting it.” For a variety of reasons she did not enumerate – but which probably include legal advice relating to a possible congressional investigation of their Pentagon and CIA sources – she and Boal have felt it necessary to restrict their public comments about the movie and the disparate reactions to it. After the lengthy defense of the film’s veracity by investigative journalist Mark Bowden that ran in the Atlantic last week, the conversation may begin to trend in a more balanced direction. (Moore told the filmmakers he is also considering writing something about it.)

“In case anyone is asking, we stand by the film,” Boal said in accepting the best-picture award, defending his half-journalistic, half-novelistic approach by saying he was more concerned about the way people would understand the film a few years from now, once the immediate political controversy has died down. "I think at the end of the day we made a film that allows us to look back at the past in a way that gives us a more clear-sighted appraisal of the future," he concluded.

On a lighter note, Boal listed the previous multiple winners of the NYFCC’s best-director prize, a roster that includes John Ford, Fred Zinnemann, David Lean and Robert Altman. With two wins in four years (for both best director and best picture), he suggested that Bigelow now belongs in that company. For the first and only time of the evening, the statuesque and remarkably composed Bigelow appeared overcome by emotion, covering her face with her hands.

Accepting the best-actress award for her role in Terence Davies’ relatively unheralded wartime romance “The Deep Blue Sea,” Rachel Weisz was at once gorgeous, gracious and funny, saying she had shared the surprising news “with my English husband over a cup of tea and a digestive biscuit.” (Said husband being Daniel Craig, the current James Bond and international heartthrob.) Collecting the best-actor prize for “Lincoln,” Daniel Day-Lewis was brief and elliptical as ever, but clearly moved by the warm reception. This was his fourth best-actor prize from the group, following “My Left Foot” in 1989, “Gangs of New York” in 2002 and “There Will Be Blood” in 2007.

In his trademark rapid-fire delivery, Kushner thanked the NYFCC for a “narrow fourth-ballot victory” in accepting the screenplay prize, quipping that he thanked those who voted for other writers too, “only not quite as much.” Matthew McConaughey started out just fine in accepting the supporting-actor award (for “Magic Mike” and “Bernie”), denying Steven Soderbergh’s claim that a female extra on “Magic Mike” had torn off his G-string and tried to explore a bodily orifice. But after discussing his affectionate relationships with both Soderbergh and “Bernie” director Richard Linklater, McConaughey wandered into a vague and uncomfortable discussion of his family life and his acting guru, and impatient applause broke out before he was finished.

Katie Couric introduced her pal Sally Field to accept the supporting-actress prize, and Field was very moving in discussing Mary Todd Lincoln as both the dramatic role of a lifetime and a symbolic redemption for the countless women who longed to take a role in public life but could not. Emmanuelle Riva, the elegant 85-year-old star of Michael Haneke’s “Amour,” accepted the foreign-language prize in Haneke’s stead, telling us winsomely (in French) that she found the American mixture of humor and seriousness invigorating. (I’m not quite sure that wasn’t a rebuke.)

The evening’s hostile vibrations came early and unexpectedly, when an evidently soused individual at the table next to mine first objected loudly to Chris Rock’s introduction to the Ken Burns production “The Central Park Five,” winner of this year’s documentary prize. When Rock said that the film demonstrates how “we all got it wrong” in the infamous 1989 “Central Park jogger” rape case, the man shouted out, “No, we didn’t!” (Perhaps he subscribes to the lingering right-wing meme that the five young men originally arrested and convicted of the crime are indeed guilty, although they have since been officially exonerated.)

A few minutes later it got worse, when Moore was halfway through an eloquent introduction to journalist-turned-filmmaker David France’s wonderful AIDS activism documentary “How to Survive a Plague,” winner of the award for best first film. Moore noted that ACT UP and other 1980s AIDS activists had blockaded roadways, pied politicians and shut down a mass in St. Patrick’s Cathedral. “I particularly like that one,” he said. At that, our friend at the next table – apparently the guest of a prominent NYFCC member -- went ballistic. “Drop dead!” he called out. “Fuck you!”

Moore is no stranger to public abuse, and interrupted himself to observe that he spent a year at seminary and demonstrate that he still knew the traditional beginning of the Latin Mass. Several people in our vicinity tried to shut up the bristly, drunken fellow, whose female companion suddenly appeared convinced she didn’t know him. His predictable response was: “No! You shut up!” Apparently not content to have told someone who was introducing a film about AIDS to drop dead, he began muttering that no one would ever make those kinds of remarks about the Jews. Beat that, Academy Awards!

Shares