Plagiarism, lying, fabricating quotes, repurposing old work as new, assuming false identities to promote themselves and tear down their rivals — is there no end to the mischief and malfeasance today's authors get up to? Many would call modern-day publishers even worse, peddlers of thinly veiled smut and sensationalistic rubbish, derivative rip-offs and trashy celebrity bios. Are publishers not intent on (and ingenious at) ripping off any ink-stained wretch unfortunate enough to come under their thrall? Literary culture as we know it must surely be staggering into its final, degraded stage — am I right?

Not so fast. I recently came into possession of a reprint of an old pamphlet, titled "An Author to be Lett," written by the English poet Richard Savage in 1729; its contents serve as a reminder that it was ever thus. The work purports to be a prospectus discovered in a "leathern case, which had once been red, but was grown black with Grease" that had been "accidentally drop'd near the Mews Gate," a London neighborhood known for its concentration of booksellers. The document's alleged author, one Iscariot Hackney, was meant to stand for the entire scribal community known as Grub Street, a conglomeration of down-at-heel, mercenary writers serving the thriving periodical press as well as a booming book trade. A "hackney" was a horse (eventually a cab) that could be hired by the hour, and in time writers operating on the same principle would become commonly known as hacks.

However disgraceful or unprincipled you may think the scribblers of today, rest assured that their 18th-century equivalents were at least as bad and probably worse. Furthermore, the laments and recourses of struggling writers have changed very little in the past three centuries.

Despite possessing no education to speak of, Iscariot Hackney boasts of having cobbled together works "on every Branch of Learning" with the help "of Indexes and technical Dictionaries" (the Wikipedias of their day). He has, he says, peddled partisan political gossip for the price of "a Pot of Ale." His particular specialties, however, are various permutations of froth and snark: "I am a great Joker, and deal in Clenches, Puns, Quibbles, Gibes, Conundrums and carry Whichits," he crows. ("Clench," according to the Oxford English Dictionary, can mean "to talk against." A "carriwitchet" the OED characterizes as "a hoaxing question or conundrum" and was, says Jesse Sheidlower, the OED's editor at large, "a vogue word among such types.") Were there cat photos around to caption, Hackney would surely have answered the call.

Hackney blithely relates that to make ends meet he has penned "Obscenities and Profanities" to be published under the names of such celebrated authors as Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope, that he has "translated from the French what they never wrote," and that he has become an expert at "finding new Titles for old Books." Today's producers of spam books for the Kindle store will find in him an unsung predecessor. Hackney also reports writing true-crime accounts to coincide with the executions of famous perpetrators and dashing off largely bogus biographies of distinguished people, embellished with illegally obtained private documents. He has, he claims, ghost-written verse for gentlemen at court wishing to pass themselves off as literary types.

"An Author to be Lett" illustrates how the dreams of hard-up writers have remained remarkably constant over the years. "I wish my portrait might shine in Mezitento thro' the Glass-Windows of Picture-Shops in Fleet-Street, and St. Paul's Church-Yard; then should I be gaz'd on with Admiration by Mercers 'Prentices," Hackney confesses, much like an aspiring novelist fantasizing about seeing his photo in the window of Barnes and Noble. "I have sometimes taken it into my Head that I might make a Fortune writing for the stage," he explains, a brother-in-arms of every laptop-toting hopeful camped out at a Williamsburg cafe to work on a screenplay.

And if worse comes to worse, Hackney admits, he can always teach — albeit as a "Travelling Tutor to some young Gentleman," rather than in an MFA creative writing program. Although ignorant of most of the subjects in which young gentlemen of the time were supposed to be educated, Hackney is confident he can impart much on "where there were good Wine, good Beds, buxom Girls and tall Steeples." (I'm pretty sure that last item is an anatomical joke, and not an advertisement of religious or architectural expertise.) Above all, Hackney is capable of instructing his pupil on "the Laws of his own country," having so often "conversed with Baliffs and petty-fogging Attornies" (i.e., been arrested for not paying his bills).

In the character of Hackney, Savage was mocking the typical Grub Street opportunist, but he knew whereof he spoke when it came to the lot of the destitute author; he would die in debtor's prison in 1743. In writing "An Author to be Lett," Savage was carrying water (and whichits) for a more prominent author: Pope, who at the time was engaged in a bitter feud with the infamous publisher and bookseller Edmund Curll. (Curll's extraordinary life -- the object of much mythologizing and dubious legend -- is the subject of Paul Baines and Pat Rogers' fascinating 2007 book, "Edmund Curll, Bookseller.") Hackney may represent the average venal Grub Street hack of the early 1700s, but Curll (whom Hackney claims to have both worked for and ripped off), was anything but run-of-the-mill. He is surely a leading candidate for the worst publisher of all time.

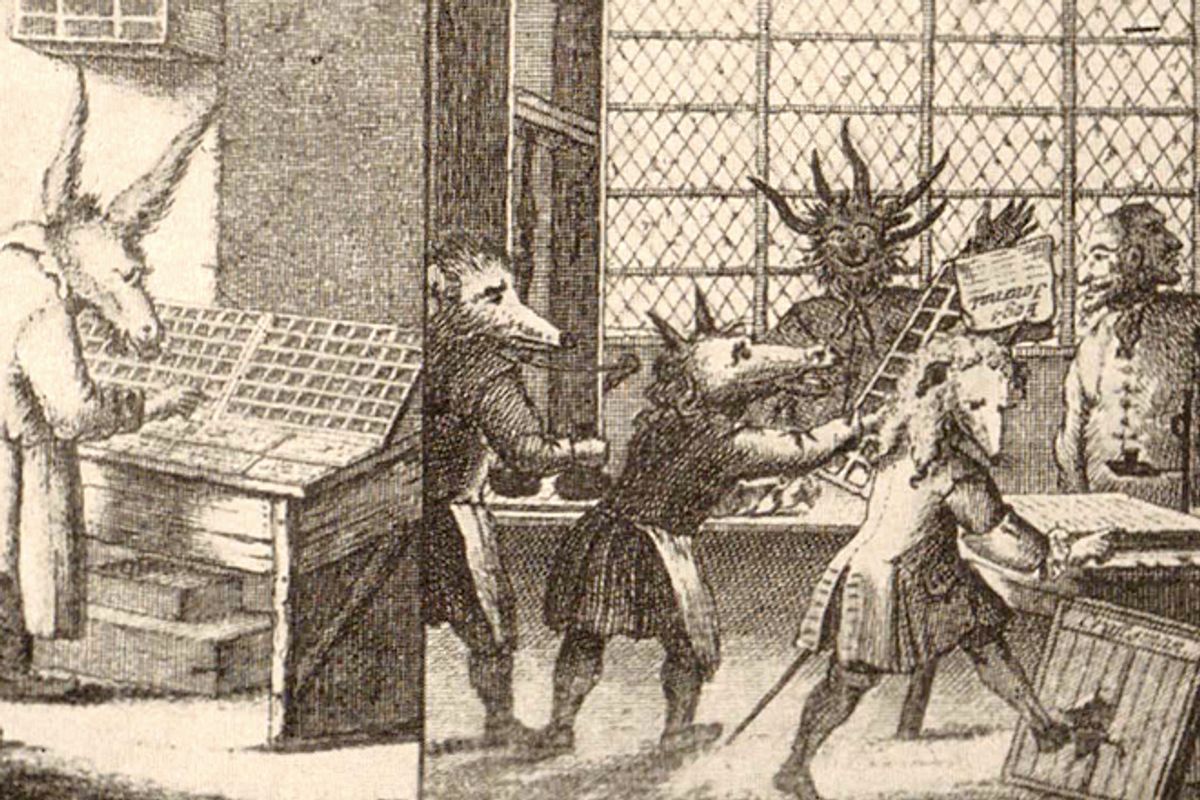

Curll was rumored (by Henry Fielding among others) to keep a team of hacks confined to a garret, where they churned out a high volume of disreputable and highly disposable texts, like an 18th-century outpost of the Gawker Media empire. He incurred the formidable wrath of Pope by publishing works by the poet and his friends without permission. Curll flourished in an unstable publishing environment, at a time when the state no longer engaged in pre-publication censorship and when copyright law, still a relatively new phenomenon, was imperfectly enforced. It was a cultural free-for-all, and in Curll Pope saw personified the gutter press that he, as a sanctified champion of highbrow literature, needed to slap down. Curll and various other writers Pope disdained became the theme of his great satirical epic poem, "The Dunciad." (Savage supplied Pope with much of the scurrilous dish it contained.)

Without question an inveterate scoundrel, Curll was forever printing works (including "The Dunciad"!) without permission or payment to their authors. His press was known for cranking out highly inaccurate quickie biographies of the recently deceased, sometimes composed entirely of testimonials solicited from the dead person's friends, but more often featuring baseless scandal mongering and calumny. Curll excelled at obtaining wills, private correspondence and other papers, and it was in a copyright lawsuit filed against him by Pope that the English courts established that the author of a letter retains the rights to its content, regardless of who possesses the physical letter itself. (This principle was invoked in a recent dispute over the proposed publication of some J.D. Salinger letters.)

Curll published everything from religious tracts to outright pornography, a mainstay of his business. He put out what was probably the first example of flagellation erotica ever published in English, a translation of the Latin text "De Usu Flagrorum." Another big title for him was "Venus in the Cloister," which may explain why Iscariot Hackney expresses the intention of encouraging any future pupil to "run away with a Nun." For several decades, the word "Curlicism" was synonymous with smut publishing, and Curll served prison time for printing both the flogging book and nun-related porn. He was in and out of court on charges of indecent and libelous publication -- as well as copyright violations -- for most of his career.

Curll also had the distinction of both acting as a government informant (snitching on fellow publishers for printing dissident works — whether they were actually guilty or not) and being convicted of revealing state secrets. He accomplished the latter by publishing the memoirs of a Scottish spy. For this crime he became the last English literary figure to be literally pilloried, although he managed to convince the public that he had published the material out of patriotic devotion to the late Queen Anne. As a result, he was not pelted with garbage while standing in the stocks.

There were many salvos in the Pope-Curll wars, and Pope did not restrict himself to the high road. On one occasion, he arranged a meeting with Curll in an ale house and poisoned the publisher's beer with an emetic. Then he bragged about doing so and claimed that Curll was dead. Curll responded by publishing anti-Pope satires and diatribes, while proclaiming that he would be the publisher of the poet's works from then on. Later he opened a bookstore called "Pope's Head." People who moan about the lack of entertaining feuds in today's mild-mannered literary scene would probably have loved 18th-century London, though you would definitely want to think twice before going out for a drink with any of them.

Pope's name endures as one of the language's great poets, and Curll is largely forgotten except as a prime target of Pope's ire and ridicule. As we look back across a distance of nearly 300 years, what we see are the giants -- Pope, Swift, Samuel Johnson (author of a biography of Savage) and other titans -- and not the minor figures, however colorful, who plagued or flattered them and otherwise made up the milieu in which they spent their lives. When viewing a landscape from miles away, we only discern the big things, like mountains or towers, not the smaller details like trees or houses. But to someone on the spot, the trees and houses loom large, just as the Curlls of our time -- the James Freys and Greg Mortensens and E.L. Jameses -- take up a lot of space in our conversations, Twitter feeds and best-seller lists. So yes, it looks bad from where we stand, but give it time.

Shares