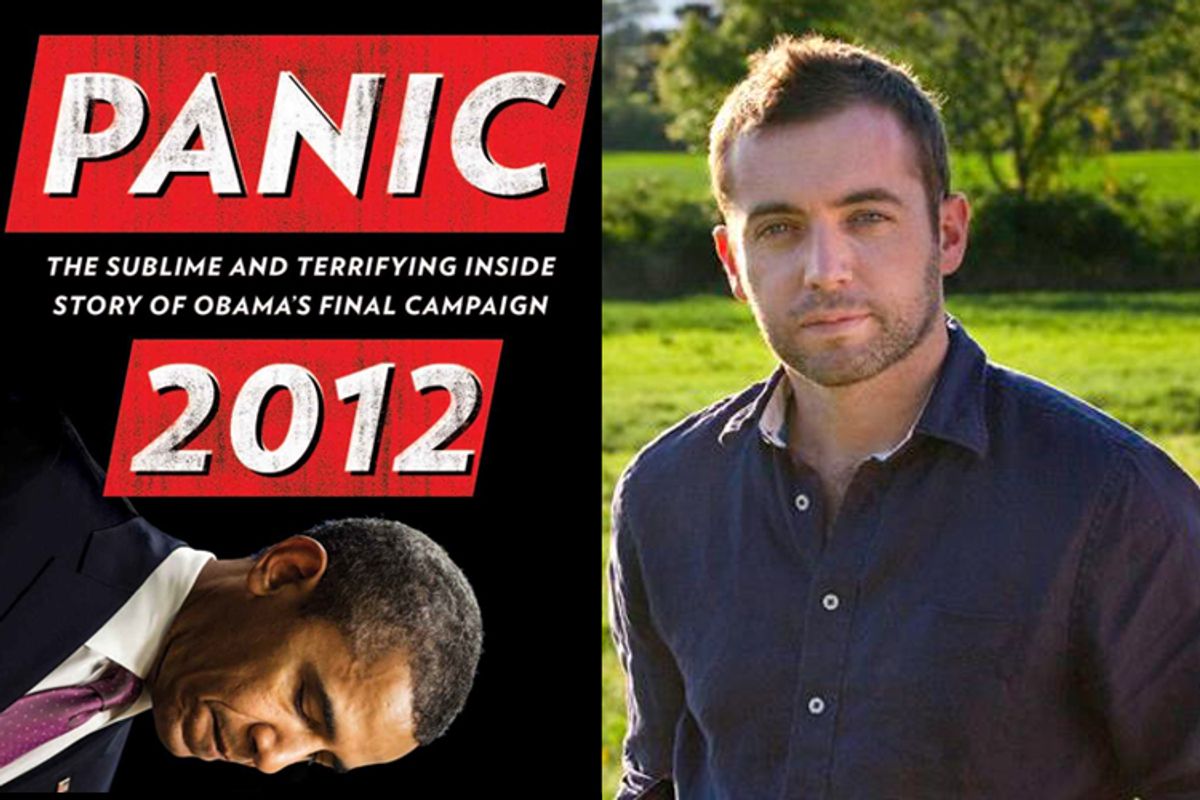

After the death of Richard Ben Cramer — whose "What It Takes: The Way to the White House" beautifully crystallized the 1988 campaign but was harshly received by his campaign-trail colleagues — and given the success of John Heilemann and Mark Halperin's dull, gossipy book and HBO's movie adaptation of "Game Change," it's hard not to feel as though the campaign book is dead. The long-form, retrospective appraisal of the quadrennial cycle used to be done by Newsweek. Now BuzzFeed is attempting to get in the game with correspondent Michael Hastings' often-profane "Panic 2012: The Sublime and Terrifying Inside Story of Obama's Final Campaign." The book, which tells of Hastings' often contentious relationship with the Obama press shop during the campaign and with other reporters, comes out today. We spoke with Hastings about the difficulty of writing long form and of brokering access to political figures.

Why bother writing a campaign book at all, when working for a website means you're filing quite frequently?

I got my start in political reporting, as a reporter on the Newsweek election project in 2008. But so much of campaign journalism, if you read as it goes on, it tells you nothing. In the past you could make an agreement with the campaigns. But in 2012, the campaign officially said, "We're not going to cooperate with any book projects." You have a sort of shift in terms of what's even possible. But there's so much of the things you find in the campaign, and there weren't the opportunities to write them as I wanted to in real time. The beauty of "What It Takes" is that it tackles one of the most dramatic tales in life, a presidential election. So you want to attempt to go back to that story, and see what's new, what's changed.

Does the utter restrictiveness of the Obama campaign, as chronicled in "Panic 2012," seem like a specific response to a specific situation, or the new manner of dealing with the press across the board?

I think whatever organization you're dealing with has to make their specific choices. They'll give access if giving access at the time is going to benefit them -- or if they're interested in benefiting the idea of a democratic free press. Will the pendulum swing back? I don't think so. The Obama reelection campaign doesn't need to give access. The Obama primary team did need to give access. It depends on the situation. But they don't mind giving access as long as you don't say what you've learned. They don't mind bringing you in to this small circle as long as you don't speak out of school. One of the examples in the book is when I was at a 500-person speech with the mayor of Chicago. I asked him a question afterwards, fairly politely, and he says, "What you just saw is off the record." This is not Syria! We're not in an authoritarian regime. Just because you say something didn't happen -- it still happened. People involved in the campaign: I hope they see the value of it, even though everything they say can get turned into a Drudge headline and ruin their day.

Were you worried about compromising future access by, for instance and for lack of a better term, portraying Mitt Romney as a real dick?

Did I write that in the book? That sounds true to me. I never worry about it. For instance, when I wrote about the fact of how we had off-the-record drinks with Obama. In terms of the rules, that was following the rules. And I didn't want to cover Mitt Romney. I felt like I just knew I was not coming from the same planet as that guy and therefore there were people able to savage him on a daily basis better than I'd be able to do. That wouldn't have been satisfying. Obama's the more interesting story: the first black president running for reelection during this historic time of economic crisis. But what campaign journalism do you even remember?

Jason Horowitz's coverage of the young Mitt Romney sticks out.

Jason Horowitz is in the tradition of someone who does exciting campaign journalism. But no one's ever won a Pulitzer for campaign journalism. But people have won Pulitzers for books about campaigns. "What It Takes" didn't win a Pulitzer, which is more proof of how the people who give prizes have their heads up their asses.

Why did you put so much first-person content in your narrative -- feuds among your cohort, emails with your boss and colleagues? It feels at times like a version of Tom Wolfe's "New Journalism."

There are no real rules. The only rule is: Does it work or not? What I was trying to do was just to challenge myself as a writer and add an intense first-person narrative, mainly because I always love reading first-person narratives. I generally like that style. Can we weave these styles together? Is that something that's possible? Is that something you'd want to read?

I wanted to be able to take all the first-person stuff out so someone could read the book and say, that's solid reporting there. You can kind of stir things up in a way and try to dramatize and add a level of excitement for people reading it. If people are not entertained by my mood swings, scrapes and derring-do, they can write a bad Amazon review. I was worried I wasn't going to have anything to write about in first person then [the Obama campaign] tried to kick me off the plane. Thanks for the conflict, guys!

How will your book differ from the "Game Change" follow-up due out this year?

They're doing their own thing and I'm doing my thing. so i don't -- it'd be interesting to see what the appetite for this election is going to be later this year. We were trying to do its own unique thing. If you're a junkie, if you're a political junkie of the methamphetamine, highest fucking order of Bill W., this'll give you that fix. I wanted to do that but also do a more exciting story. I think it's good to check in on the press corps, and also examine where they stand, to revisit what does the modern campaign press look like. What are the class distinctions? it's always good to -- not update that, but pry some new element out of it. It's not that I think the whole system's a sham, but rather going into the process of how these interpersonal relationships are made. Rather than making a farce of it all, which is not an inappropriate thing to do, it's trying to do it straight ... The thing is it's a brutally easy gig. There's all this prestige but the journalism you're doing as journalism -- you're not uncovering the next national security crisis. It's the most absurd possible thing while having the highest possible take.

Shares