Richard Nixon’s Checkers speech — delivered just five days after the New York Post reported wealthy backers had set up a fund for his day-to-day expenses — was seen by some 58 million people, or about a third of the population of the United States. It lasted thirty minutes and was to be forever identified by its reference to a cocker spaniel named Checkers. It was like nothing ever seen in American politics, set apart by its intimacy, its pathos, the apparent revelation of a private life from a public man, and its use of television. Its structure was a trial lawyer’s closing (or, perhaps, opening) argument, which ranged from the explanatory to the exculpatory to the defiant; buried within it was not only Nixon’s defense of himself, but occasional jabs at his opponents and probably at General Dwight Eisenhower, his running mate. It is still a remarkable document.

The set was simple: Nixon sat behind a desk, his hands loosely clasped over his notes, and Pat Nixon was several feet away in a chair that seemed too large for her. Looking earnestly into the camera, Nixon said:

My fellow Americans, I come before you tonight as a candidate for the Vice Presidency and as a man whose honesty and integrity have been questioned. Now, the usual political thing to do when charges are made against you is either to ignore them or deny them without giving details.

I believe we’ve had enough of that in the United States, particularly with the present Administration ...

I have a theory, too, that the best and only answer to a smear or to an honest misunderstanding of the facts is to tell the truth. And that’s why I’m here tonight. I want to tell you my side of the case.

Nixon went on to do just that, often conducting a dialogue with himself in a style and rhythm that he would continue to employ and to improve upon throughout his public life:

I’m sure that you have read the charge and you’ve heard it said that I, Senator Nixon, took $18,000 from a group of my supporters.

Now, was that wrong? And let me say that ... it isn’t a question of whether it was legal or illegal; that isn’t enough. The question is: Was it morally wrong? I say it was morally wrong if any of that $18,000 went to Senator Nixon, for my personal use. I say that it was morally wrong if it was secretly given and secretly handled. And I say it was morally wrong if any of the contributors got special favors for the contributions they made.

But that never happened, Nixon insisted. And then he posed another question to himself: “Well, then, some of you will say, and rightly, ‘Well, what did you use the fund for, Senator?’ ‘Why did you have to have it?’” That permitted him to explain the economics of a Senate office — his salary, his travel expenses, and the rest. But there were, he added, other expenses that needed to be covered for which there was no federal reimbursement. How, Nixon asked, does one pay for that — and do it legally? “The first way,” he said, “is to be a rich man. I don’t happen to be a rich man; so I couldn’t use that one.” Then, using the language of quiet insinuation that infuriated his detractors, he took the night’s first slap at the Democrats — starting with Senator Sparkman — while bringing Pat Nixon into an increasingly personal narrative:

Another way that is used is to put your wife on the payroll. Let me say, incidentally, that my opponent, my opposite number for the Vice Presidency on the Democratic ticket, does have his wife on the payroll, and has had her on his payroll for ten years — for the past ten years.

Now just let me say this: That’s his business and I’m not critical of him for doing that. You will have to pass judgment on that particular point. But I have never done that for this reason: I have found that there are so many deserving Washington stenographers and secretaries that needed the work that I just didn’t feel it was right to put my wife on the payroll. My wife ... used to teach stenography and she used to teach shorthand in high school. That was when I met her. And I can tell you that she’s worked many hours at night and many hours on Saturdays and Sundays in my office and she’s done a fine job. And I’m proud to say tonight that, in the six years I’ve been in the House and the Senate of the United States, Pat Nixon has never been on the government payroll.

Then, with a curious, unchallenged aside about Reds-in-Washington, he said:

I felt that the best way to handle these necessary political expenses of getting my message to the American people and the speeches I made — the speeches that I had printed — for the most part concerned this one message of exposing this Administration, the Communism in it, the corruption in it. The only way that I could do that was to accept the aid which people in my home state of California, who contributed to my campaign and who continued to make these contributions after I was elected, were glad to make.

And, he added, “I am proud of the fact that not one of them has ever asked me for a special favor.” (A claim by the columnist Drew Pearson that Nixon once asked the American ambassador in Havana to intervene on behalf of the fund’s organizer, Dana Smith, over a gambling debt was never substantiated.)

At that point, Nixon posed yet another question to himself: “Let me say, incidentally, that some of you may say: ‘Well, that’s all right, Senator; that’s your explanation, but have you got any proof ?’” And then Nixon got to the audit of his finances by Price, Waterhouse, accompanied by the legal opinion from the law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, which he called “the biggest law firm and one of the best ones in Los Angeles” and which he said found him blameless. Nixon, though, was far from done with this part of his talk, and moving past the audits and the crash course in political economics and Senator Sparkman, he became steadily more autobiographical:

But then I realize that there are still some who may say, and rightfully so ... “Well, maybe you were able, Senator, to fake this thing. How can we believe what you say? After all, is there a possibility that you got some sums in cash? Is there a possibility that you feathered your own nest?”

And so now what I am going to do — and this is unprecedented in the history of American politics — is give to this television and radio audience a complete financial history: everything I’ve earned; everything I’ve spent; everything I owe.

At that, Nixon began to talk about some of the difficult circumstances of his childhood, although he did not mention the deaths of two brothers. He told of working in the family grocery store in East Whittier and of supporting himself through college and how, in 1940, “probably the best thing that ever happened to me happened. I married Pat.” And he spoke of how, as a young married couple, they struggled, and then of his time in the Navy, where his “service record was not a particularly unusual one ... but I was just there when the bombs were falling," and he gave details about his scale of living — a 1950 Oldsmobile, an $80-a-month apartment in Virginia — and the size of their mortgage in California and other debts, going to a line that by now he had perfected: “But I should say this, that Pat doesn’t have a mink coat. But she does have a respectable Republican cloth coat. And I always tell her she’d look good in anything.”

It was then that Nixon came to the part of his speech that is most remembered, quoted, and mocked:

One other thing I probably should tell you, because if I don’t they’ll probably be saying this about me too: We did get something — a gift — after the election. A man down in Texas heard Pat on the radio mention the fact that our two youngsters would like to have a dog ... It was a little cocker spaniel dog in a crate that he’d sent all the way from Texas, black-and-white, spotted. And our little girl Tricia, the six year old, named it Checkers. And you know the kids, like all kids, love the dog and I just want to say this right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we’re gonna keep it.

More important than Checkers, though, was the last part of his speech, at first subtle and then class-conscious and accusatory, wholly unlike the rest of it:

I believe it’s fine that a man like Governor Stevenson, who inherited a fortune from his father, can run for President. But I also feel that it’s essential in this country of ours that a man of modest means can also run for President, because, you know, remember Abraham Lincoln, remember what he said: “God must have loved the common people — he made so many of them.”

He was proud of coming up with the Lincoln quote, and he followed that by noting that Stevenson had a fund of his own (it was used to supplement the salaries of some Illinois state employees and was considerably larger and less transparent than Nixon’s), adding:

I don’t condemn Mr. Stevenson for what he did. But, until the facts are in there, a doubt will be raised ...

I would suggest that, under the circumstances, both Mr. Sparkman and Mr. Stevenson should come before the American people, as I have, and make a complete financial statement as to their financial history, and if they don’t, it will be an admission that they have something to hide. And I think that you will agree with me. Because, remember, a man who’s to be President and a man who’s to be Vice President must have the confidence of all the people.

From there, after a campaign detour to blame Truman and the Democrats for Communist advances in China and the war in Korea, he arrived at his finale — part plea, part preemptive attack, and, in his suggestion that the ultimate decision rested with the party, impudently circumvented Eisenhower’s authority:

But the decision, my friends, is not mine. I would do nothing that would harm the possibilities of Dwight Eisenhower becoming the President of the United States. And for that reason I am submitting to the Republican National Committee tonight, through this broadcast, the decision which is theirs to make ...

But let me say this last word. Regardless of what happens, I’m going to continue this fight. I’m going to campaign up and down America until we drive the crooks and the Communists and those who defend them out of Washington. And, remember, Eisenhower is a great man. Believe me, he’s a great man. And a vote for Eisenhower is a vote for what’s good for America —.

He’d been cut off in mid-sentence — he’d run out of time — and he was furious at himself for not being able to give the address of the Republican National Committee, to whom he had asked people to wire support. Above all, he thought that he had failed to defend himself, and what made him even more despondent was the ominous, continued silence from General Eisenhower. All he’d heard before going on the air was that bizarre conversation with Tom Dewey, and after the speech, all that he heard came in fragments through wire service accounts. At the Ambassador Hotel, the telephone lines were jammed — it was hard to get through. Marje Acker had been watching TV in Rose Mary Woods’ room, but the only way to call the room was to go through the overloaded hotel switchboard.

Nixon at first had no real sense of what he’d just done, because no one had ever done it before, but it did not take long for him to realize that perhaps he needn’t despair; as he left the El Capitan, he was cheered by people who’d been waiting outside. And even without a proper address for the Republican National Committee, telegrams were already coming in at the rate of about four thousand an hour. Loie Gaunt, who worked on Nixon’s Senate staff, was helping out at the Washington Hotel and, after the speech, she stayed put, answering calls from people who told her that they’d been moved.

A positive consensus quickly appeared, much of it close to the somewhat conditional view of the Herald Tribune, whose editorial insisted that the final decision rested with General Eisenhower and, while not affirming full support of Nixon, now said that he “will emerge from this ordeal ... not only as a better known but as a bigger man than before.” But there were dissenters — “this mawkish ooze ill became the role of a man who might become President,” one paper said — and even Nixon’s allies found something unsettling about the performance. One might have said of him, as Trollope wrote of the lawyer Mr. Samuel Dockwrath, “He talked well and to the point, and with a tone of voice that could command where command was possible, persuade where persuasion was required, mystify when mystification was needed, and express with accuracy the tone of an obedient humble servant when servility was thought to be expedient.”

Eisenhower had watched Nixon’s performance from a sofa inside the manager’s suite of offices at the Cleveland Public Auditorium, where he was scheduled to speak later that night and where the audience had listened to a radio broadcast of the speech. Mamie sat beside him on a couch, and they were joined by about twenty friends and staffers, among them Bill Robinson, who, Bob Humphreys observed, had quickly become an “enthusiastic Nixon supporter.” Eisenhower, when he spoke at an outdoor rally afterward, said, “I have seen many brave men in tough situations. I have never seen any come through in such fashion as Senator Nixon did tonight.” Then, in an odd digression, he compared Nixon to George Patton. “I had a singularly brave and skillful leader,” he said. “He was my lifelong friend. We were intimate. He committed an error” — a reference to when General Patton went briefly mad and slapped a soldier who was suffering shell shock. “It was a definite error. There was no question about it. I believed that the work of that man was too great to sacrifice.” Ike continued, “I happen to be one of those people who, when I get in a fight, would rather have a courageous and honest man by my side than a whole boxcar of pussyfooters.”

But Eisenhower was not entirely pleased by Nixon’s performance. Rather there were things about it that he did not like at all, and his anger was obvious to some of those who watched him while Nixon spoke. Nixon had dodged the question of resignation — he said “I am not a quitter” but didn’t add, as his notes had it, “I could insist on stay” [sic] — but Eisenhower did not appreciate Nixon’s asking viewers to wire their support to the Republican National Committee, which was no less than an attempt to take the decision away from him; and he had looked distinctly annoyed when Nixon talked about all the candidates revealing their personal finances. All the candidates included Eisenhower, and that meant revealing how a special tax decision permitted him to treat the $635,000 he had been paid for his war memoir as capital gains rather than as taxable earnings.

Eisenhower had sent a congratulatory (though still noncommittal) telegram to Nixon, but its entire text had gotten lost among the others, and the part that Nixon saw that night sounded less like congratulations and more like a summons: “Your presentation was magnificent,” the general had said, but went on to reassert his authority in the matter: “While technically no decision rests with me, yet you and I know that the realities of the situation will require a personal pronouncement, which so far as the public is concerned, will be considered decisive. In view of your comprehensive presentation, my personal decision is going to be based on a personal conclusion. To complete the formulation of that personal decision, I feel the need for talking to you and would be most appreciative if you could fly to see me at once. Tomorrow night I shall be at Wheeling, West Virginia.”

That was just the sort of message to provoke Nixon, who had been on edge for days, into throwing a minor tantrum, telling Murray Chotiner, who had rarely left his side during this period, that he’d had enough — that he’d expected a decisive answer. And if the broadcast hadn’t satisfied the general, what was there to do? At that point, he dictated a telegram of resignation to Rose Mary Woods, who had no intention of sending it. She knew her boss well enough to know when he was posturing.

* * *

By the morning after the speech, Nixon’s mood had improved — reflected in a note that he dashed off to the Nixon family friend Helene Drown:

Helene — tell the sisters they must have been praying for me last night. 5 minutes before it started, I didn’t think I could do it. Then I sat down put my head in my hands + prayed. God Thy will be done not mine. Well I guess they came through for me.

He began to feel proud of what he’d done.“It was like before starting in a football game — you’re all keyed up, you’re praying, your knees are full of water but then they blow the whistle and you get in there and hit the line,” he said. “I probably had been preparing to do it all my life.” His restored confidence was accompanied by an impulse of insubordination — a determination to head to a previously scheduled stop in Missoula, Montana, rather than follow orders to meet Eisenhower in Wheeling.

Bob Humphreys and Art Summerfield, the Republican National Committee chairman, were afraid that Nixon would do something rash, and at 6 a.m., they telephoned Chotiner. As Summerfield talked, Humphreys passed him a scrawled note — actually many notes that together made up a single anti-poetical scrawl that looked like haikus strung together:

Art

tell him

to intercept

Dick before

he says something

to press

Ike’s phone number

Superior 1-6979

Dick should hold at

that airport

until you

have talked

to Ike

He

Must

Intercept

Nixon

They’re crappin’

you—

Nixon has

not left

yet

—Main 1504—

opened up

between you

and Dick at

airport while

you get Ike

out of bed—

Tell Dick’s

guys to open

the wire

Eisenhower and Nixon were poker players, and Nixon, now that he held a better hand, was prepared to bluff. Chotiner went so far as to tell Summerfield that Nixon had written a resignation letter. As for going to Wheeling, Chotiner said, “Unless you can give us your personal assurance direct from the General that Dick will stay on the ticket with the General’s blessing, I think I can persuade him. I know I can’t otherwise.” Summerfield then arranged for the general and the senator to talk later that day — Eisenhower in Portsmouth, Ohio, and Nixon in Missoula — and when the conversation was over, Summerfield told reporters, “I am certain that Senator Richard Nixon will remain the Republican candidate for Vice President,” and an aide let reporters know that Nixon believed he “was not a GI in this war,” and furthermore that he was “not going there [Wheeling] to be cross examined any further.” It also happened that after the Nixon party got to Missoula the candidate had a chance to read some of the messages that he hadn’t seen in Los Angeles — among them the entire wire from Eisenhower that not only began “Your presentation was magnificent” but now concluded, “Whatever personal affection and admiration I had for you — and they are very great — are undiminished.”

On the last leg of the flight, from Denver to Wheeling, Nixon fell asleep. His plane arrived at about 10 p.m., which marked the first time that a DC-6B had landed on the short hilltop runway at Stifel Field, where a crowd had gathered in the chilly night and where Eisenhower had waited for about forty-five minutes.“We weren’t sure who was going to meet us or where we were supposed to go,” Marje Acker recalled, “so Murray Chotiner said, ‘It’s always a tradition that staff get off first and the candidate and Mrs. Nixon get off last.’ After they’d cleared the stairs, Murray said he’d go down and see what the situation was. Well, he barely got to the foot of the steps — I was standing near the top, in the plane — and Eisenhower comes bounding up the stairs and he looked straight at me and said, ‘Where’s Dick?’ and I remember those piercing blue eyes.”

Nixon, who was standing with Pat at the rear of the plane, asked, "What are you doing here, General? You didn’t have to come here to meet us.”

Eisenhower put his arm around Nixon and said, “I certainly did, Dick. You’re my boy,” at which point they shook hands and Nixon, never less than uncomfortable in Ike’s presence, made an awkward joke: “This is something new — as though we’ve never done this before!” he said, almost a shout, apparently referring to their handshake. Then Eisenhower and the Nixons descended the stairs and pushed through the crowd to waiting cars, with Eisenhower saying, "You run interference — I'll follow you.” Every detail was scrutinized by reporters—about eighty of them, who had been riding on the general’s train.

On the short drive to City Island Stadium, where they were to speak, Sherman Adams, who was in the front seat, heard Eisenhower say, “You’ve had a hard time, young fellow. It was a hard thing for you to go through and I want you to know I understand that.” Eisenhower didn’t mention the strain on their relationship or the pressure to drop Nixon from the ticket; Nixon talked about the reaction to his speech. Pat Nixon and Mamie Eisenhower rode in another car where Mamie, after a long silence, finally said, “I don’t know why all this happened when we were getting along so well,” to which Pat replied, “But you just don’t realize what we’ve been through,” in a tone that ended the conversation.

At the stadium rally, Eisenhower read a telegram that he’d received in Cleveland which said, “Dear General: I am trusting that the absolute truth may come out concerning this attack on Richard, and when it does I am sure you will be guided right in your decision, to place implicit faith in his integrity and honesty. Best wishes from one who has known Richard longer than anyone else. His Mother.” (“Mom trusted Eisenhower to see the light which she believed every man has in his mind if you turn it on,” Edward Nixon said.) When Nixon spoke, he said that there were two occasions “when I think that I was prouder to be an American than any other time,” adding that both times Eisenhower was present — and that “the chills run up your back, and you realize down deep what a great and good country this is.” He told the crowd how he’d first seen the general from a high floor in lower Manhattan during the V-E Day parade in 1945 — and even then could sense “the greatness that not only makes him a wonderful candidate, but is going to make him a great President.” The second occasion, he said, was that very day, though he did not quite separate his own triumphant moment from the candidate whom he called “a great American.” It was cold in the stadium; Mamie Eisenhower shared some of her fur wrap with Pat Nixon, who was wearing her cloth coat.

Nixon then made the surprising declaration that he was pleased that Ike had not simply rushed to his defense. Rather, he said, “there has been too much of that in the present Administration. There is too much of this business of cover-up; too much of this business of clamming up whenever any charges are made against those in high places.” He added, “I want you to know that this is probably the greatest moment of my life.” After that, Senator Knowland, who was still traveling with Eisenhower, said, “Great speech, Dick,” and also, “Everything is going to be all right, Dick,” and Nixon said, “Good old Bill,” at which point he finally broke down, burying his head on Knowland’s shoulder. The photograph of the two men, one of them weeping and the other comforting him, appeared the next day in just about every newspaper in the country.

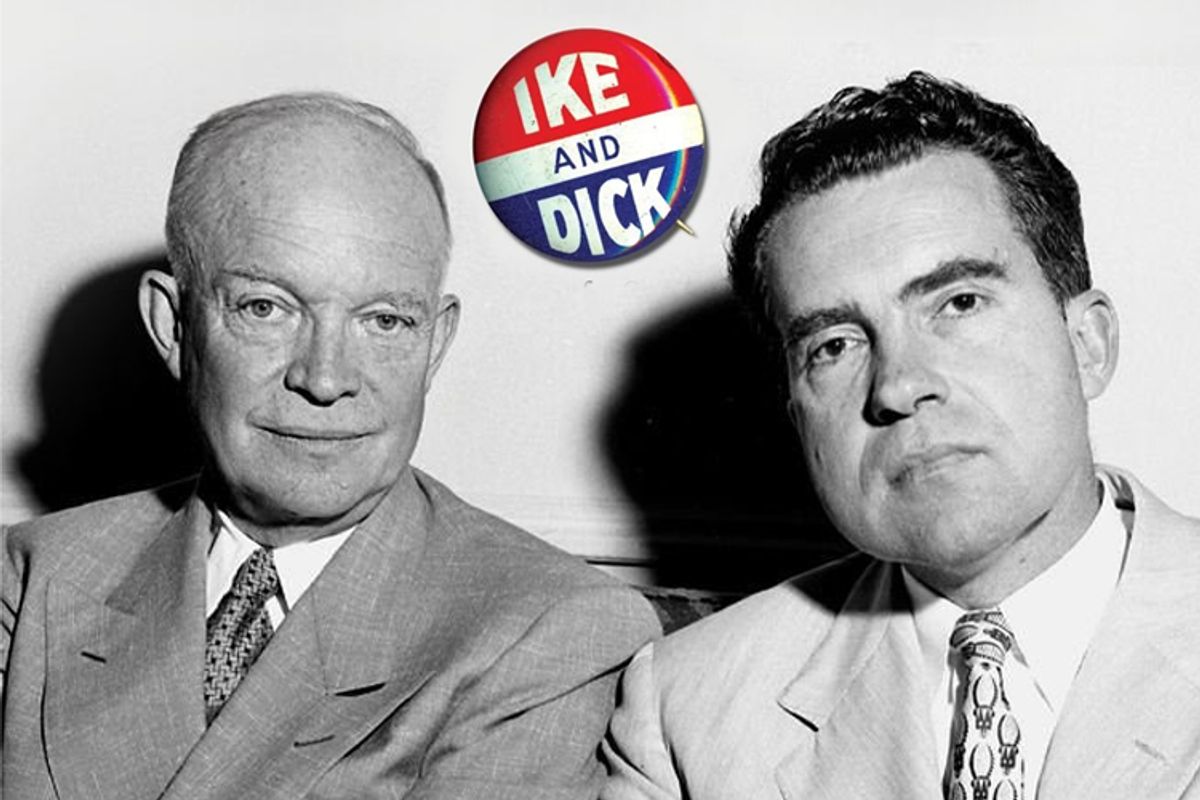

It was not, though, the greatest moment of Nixon’s life; it was more like having been inside a flaming, descending aircraft and surviving, although somewhat scalded. For despite their public scene of reconciliation — despite Nixon’s praise for Ike’s judiciousness — the two men had no reason to trust one another; in fact, after the speeches, the general summoned Dick and Pat to his quarters on the campaign train, where he quizzed Nixon about fresh rumors concerning his finances. At the not-so-young age of thirty-nine, Nixon had discovered that when it came to presidential politics, he was as disposable as the Ike-and-Dick buttons that strangers wore at campaign rallies and that his future was entirely in the hands of this forbidding figure with the amazing grin and chilly blue eyes to whom he owed everything and who owed him nothing in return. He had said that he would not crawl, yet he had become a supplicant and had come close to being broken by uncertainty and stress.

Ten years later Nixon wrote that the fund episode had “left a deep scar which was never to heal completely,” and that it “was the hardest, the sharpest ... of my public life.” His daughter Julie recalled how her father would mark the date each September 23, asking, “Did you know today is the anniversary of the fund speech?” When she asked her mother about that time, Pat Nixon replied, “Do we have to talk about this? It kills me.”

While Nixon had learned that he could not rely on Eisenhower — that his supportive words had no meaning — Eisenhower had learned that he could never regard Nixon in the same way. He was still General Ike, adored by crowds and destined to win the presidency. But he had permitted a subordinate to seize control of the campaign’s first emergency; and Nixon began to realize that Eisenhower’s vulnerabilities included an inability to confront him directly. That absence of certainty could make life harder, but at the same time, in close combat, it might leave him an opening. In any case, after the fund episode, there was no way to pretend that important decisions about Nixon’s future belonged to Eisenhower alone.

Excerpted from "Ike and Dick: Portrait of a Strange Political Marriage" by Jeffrey Frank. Copyright © 2013 by Jeffrey Frank. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Shares