Maybe the right-wingers are correct after all about America being a Christian nation -- but not quite in the way they think. One conclusion I draw from the sordid tale of Lance Armstrong and his failed attempt at public confession is that we still have the form and symbolism of public religious ritual in this country, even when we’re not aware of it. It’s like we still have the exoskeleton of Christianity around us, but the creature that once lived inside it died long ago and has been eaten by ants.

A century after Max Weber identified the “Protestant ethic” at our nation’s moral spine, America has become a smorgasbord of cultures and faiths, where organized religion is fading fast (although spiritual belief is still widespread). But our public life and our popular culture remain profoundly entangled with Christian ideas about redemption and salvation, however half-baked and bastardized they have become. Nowhere is this more obvious than in our national obsession with confession and forgiveness, which extends from reality TV to the 12-step meeting in the church basement down the street. Sit alone in a bar long enough, and somebody will start telling you about how he screwed up his marriage and that time in Florida with that girl and all that coke.

Even you’ve been hiding in a cave or living off the grid, you probably know about Armstrong, the cancer survivor and champion cyclist whose rise and fall is overloaded with improbable melodrama. A few weeks after being stripped of all his titles for doping, Armstrong did his inevitable television interview this week with Oprah Winfrey (“America’s confessor in chief,” in the words of my colleague Mary Elizabeth Williams). After many years of aggressive and insistent lying about his use of performance-enhancing drugs during his seven Tour de France victories, Armstrong has been pushed to the point of telling at least some of the truth.

Even amid the widespread mendacity and willful collective ignorance of our celebrity-centric culture, I have to admit I find the Armstrong story both shocking and depressing. I’m not talking about the drugs, which were clearly widespread in cycling. As with the downfall of Richard Nixon, it’s all about the lies and the cover-up. Until he fell silent toward the end of 2012, Armstrong had steadfastly denied every allegation of cheating, and he had legions of loyal fans at his back, ready to pounce on any journalist who dared to go after him. (It’s hard to imagine what people who believed him all along are going through.) He intimidated and browbeat underlings and opponents, and filed libel lawsuits against reporters whose claims turned out to be entirely true. Anyone who’s paid even the slightest attention to the story understands that Armstrong’s current confessional mode is entirely self-serving, the last-ditch tactic of a trapped rat.

Yet none of us expects anything different. All the moves of this dance are as familiar as the hackneyed plot of Robert Zemeckis’ “Flight,” with Denzel Washington as an alcoholic airline pilot who destroys his career with addiction and sets himself free (while going to prison!) by telling the truth. Armstrong is trying to plug himself into a classic American ritual of confession, atonement and forgiveness, one that has roots in Christian theology and is often accompanied, even these days, with explicit religious imagery. (As repellent an individual as Armstrong seems to be, at least he didn’t inflict on us any earnest discussion about his relationship with Jesus Christ.)

Of course this drama of sin and repentance in which Armstrong is struggling to find his place is much older than America. St. Augustine’s “Confessions,” at the very beginning of Christian philosophy, dwells extensively on Augustine’s bohemian youth amid the fleshpots of Carthage, and gets pretty boring after he finds the Lord. In Dostoevsky’s relentless Christian allegory “Crime and Punishment,” the murderer Raskolnikov’s final redemption is barely a footnote at the end of the book. Nor are the hypocrisy and self-interest anything new. Supposedly the 11th-century Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV spent three days kneeling in the snow to gain absolution from Pope Gregory VII, only to have Gregory overthrown and sent into exile a couple of years later.

For whatever reason American culture has a special fascination with Augustine-lite tales of fall and redemption, and the end point of this process of rehabilitation – we could call it the Clinton-Spitzer trajectory – often involves a daytime TV gig, a prison ministry or a lucrative career as an inspirational speaker. Armstrong hasn’t gotten there yet, though he probably will. For now he’s hoping to stay out of jail and hang onto at least some of his money; he can worry about rebuilding his tarnished brand and relaunching his athletic career later.

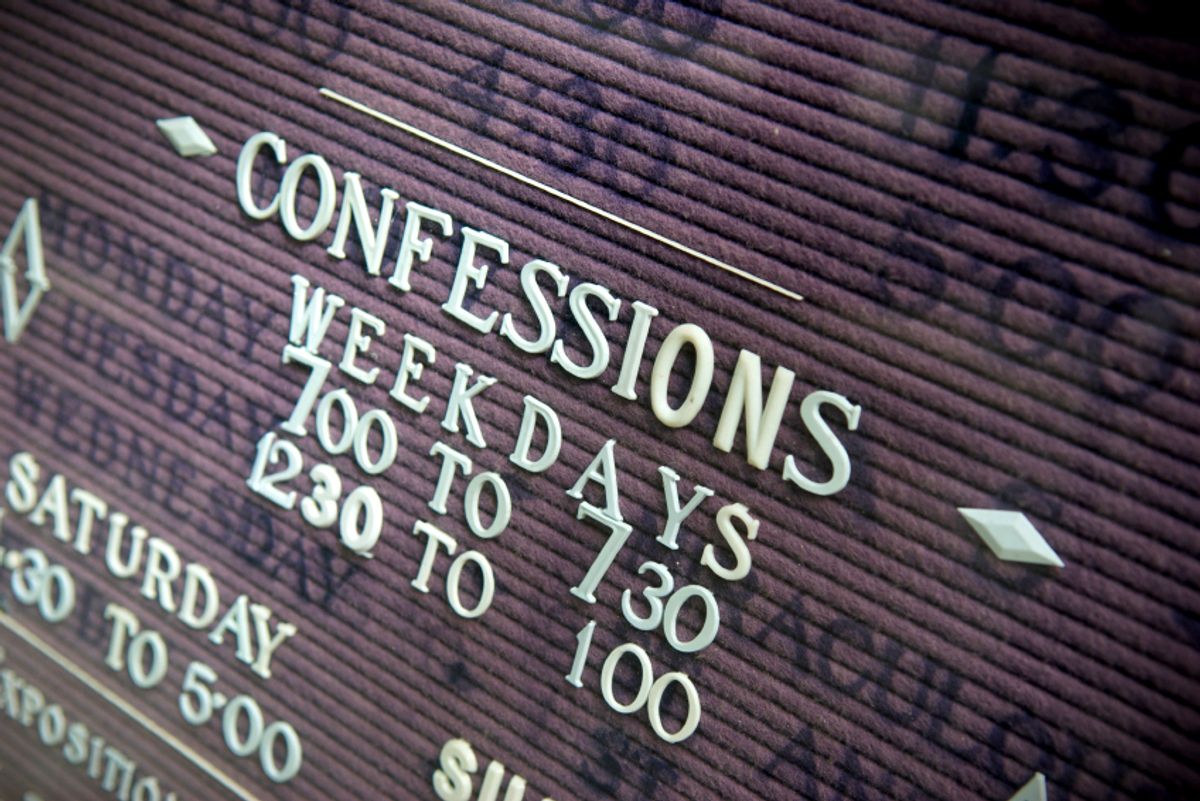

You might think that a guy with Armstrong’s resources would have been well prepared for his role in this ritual, the way young Catholics are coached on their catechism and the sacrament of confession. It sure didn’t look that way, did it? Between his twitchy, affectless delivery and his buck-passing claims that everybody else was doing it and he wasn’t the mastermind – oh no, he was just the superstar athlete around whom the entire scheme was constructed – Armstrong came off as too calculating or narcissistic to offer a direct apology or express remorse. Of course I have no idea what’s in Lance Armstrong’s heart (other than the buildup of all kinds of weird designer chemicals), and I still wouldn’t know that if he were a more compelling actor. But he does not appear to understand that the church of public opinion demands virtual sackcloth and ashes, the convincing performance of repentance and contrition.

At least for the moment, Armstrong belongs to the category of the unsatisfactory or inadequate public penitent, alongside such classic examples as Tiger Woods, Alex Rodriguez, Mel Gibson and Larry Craig. When his marriage collapsed amid multiple claims of infidelity and a bizarre late-night car accident outside his Florida home, Woods issued a carefully worded, nonspecific apology that dared to suggest that our interest in his private life was unwarranted. However much you may agree with that sentiment – and I certainly do – celebrities are never supposed to disavow their iconic, role-model status, or lament their loss of privacy. Neither Woods’ public image nor his golf game has ever recovered, and if you want to see divine agency at work that’s up to you.

With characteristic cluelessness, Rodriguez managed to make a far lesser offense than Armstrong’s – he took banned supplements for a few years in the early 2000s – seem completely obnoxious. He had crumpled, he explained, under the pressure of the richest contract in baseball history. No one will ever take Gibson’s apologies seriously again, for the simple reason that he never allows himself enough time to repent of one deranged and reprehensible act before committing another. And then there’s Craig, the champion non-apologizer of all time. Following his 2007 arrest for soliciting sex in a men’s room at the Minneapolis-St. Paul airport, the Republican senator from Idaho denied doing anything wrong, denied being gay (despite considerable evidence to the contrary) and apologized only for having pleaded guilty to something he didn’t do. (I’m not sure what it is about Idaho Republicans, but current Sen. Mike Crapo – a Mormon and supposed teetotaler -- was recently arrested for drunk driving and compelled to issue a craven public apology.)

While all those guys made asses of themselves, there are clearly levels and degrees. Woods and Rodriguez came off like spoiled, vain, rich athletes with their heads up their butts, which is not especially surprising. Gibson seemed crazy and dangerous while Craig seemed like a thoroughly reprehensible hypocrite. Like Armstrong, they all failed to grasp the role they were supposed to play in a symbolic and quasi-religious drama. Whether or not supposedly penitent sinners actually invoke the Deity or make public announcements about their period of private prayer – as Bill Clinton and Jesse Jackson both did when beset by scandal – we expect to see them abase themselves, shed tears, and undergo a low-grade media crucifixion while grim-faced family members look on.

This theatrical spectacle of public humiliation, as I see it, carries a bewildering mixture of Catholic, Protestant and contemporary New Age ingredients. It has elements of the Roman Catholic rite of absolution, in which a bureaucratic or collective intermediary – the priest, the church, the body of public opinion – assigns penance and forgives your sins. But it’s probably closer to the evangelical tradition of Bible-meeting testimony, in which you preach out all your colorful misdeeds and then declare that you have made a private contract of salvation with the Lord. As I suggested earlier, you don’t have to be Christian, or religious in any way, to pull this off. Eliot Spitzer is a non-practicing Jew, and the press conference he gave when resigning as New York governor was a classic performance of public agony and shame in the grandest pseudo-Christian tradition.

I understand that people admired Spitzer’s public mea culpa, or the six or seven different ones Clinton issued during the Monica Lewinsky scandal, because they appeared to be moments of sincerity and authenticity. For all I know they were sincere and authentic, but when it comes to public figures (or anyone else) we can never be entirely sure about that. This speaks to another aspect of the crypto-struggle between Protestant and Catholic worldviews, which is our confusion about whether people are to be judged by their words or their deeds.

In the Puritan tradition that lies at the root of American Protestantism, the central focus is on faith and the Word of God. If you’ve accepted Christ and been saved, then your sins are washed clean, both the ones you’ve already committed and (in some interpretations) the ones yet to come. Of course it’s assumed that you’ll lead a virtuous life, but if you’re actually among the elect, then whatever you do is virtuous by default. As Weber noted, being rich and successful became identified with godly virtue early in the history of American Christianity, and it’s an association we can’t quite shake.

Lance Armstrong says he’s sorry for his years of lying and cheating – or, y’know, he kind of does – and since we have no way of telling whether he means it we’re judging him on the quality of his performance (which sucked). We’d feel more kindly toward him if he’d gotten choked up, looked the camera right in its electronic eye and read out a memorized apology. But wouldn’t we be better off waiting to see how he actually conducts his life now, and what amends he can offer to all the people he has injured or insulted? Wouldn’t that be a basis for forgiving him or not doing so?

Such examples do exist. After recanting his years of racial hatred and support for segregation, Alabama Gov. George Wallace helped Rep. Shirley Chisholm, D-N.Y., pass a landmark law extending the national minimum wage to domestic workers for the first time. Ken Mehlman, a noxious Republican apparatchik and aide to George W. Bush, finally came out of the closet and has become a crucial operative in the struggle to pass same-sex marriage laws in New York and elsewhere. Those actions didn’t cancel out all the dreadful things Wallace and Mehlman did, but they mattered a hell of a lot more to real people than Oprah interviews and tearful press conferences.

But those examples stick out because they seem old-fashioned and strange, like someone believing that O.J. has diligently been looking for Nicole’s killer all this time. For one thing, Lance Armstrong is outrageously unlikely to offer any meaningful amends to anyone. For another, the entire point of the whole ritual is the show, the Clintonesque catch in the throat, the moment of televisual drama and the instantaneous leap to judgment. The snakeskin of Christianity moves around as if it were alive, but that’s just the ants. It isn’t that we don’t care about actual sorrow or thoughtfulness or repentance, but we can’t be sure they really exist. When the Pharisees brought the adulterous woman to Jesus in the temple, he drew designs in the dirt, wouldn’t let them stone her and sent the crowd away in shame. Where’s the excitement in that?

Shares